By James Connolly and Mateus Lira

Austin is considered one of the most ecological cities in the US, but due to a history of racial segregation, environmental injustice, gentrification, and misguided policies, access to housing and green space remains a privilege for wealthier residents.

Editors’ note: This post is the fourth in the Series “Green inequalities in the city”, developed in collaboration with the Green Inequalities blog. The series seeks to highlight new research and reflections on the linkages between the dominant forms of “green” redevelopments taking place in cities and questions of urban environmental justice, and the challenges and possibilities these imply for more just and ecological urban spaces.

Austin is known for being the green beacon of Texas and one of the most ecological cities in the US, with about fifteen percent of its land dedicated to parks and other green spaces and large regional preserves nearby. But access to these spaces has increasingly become a privilege for wealthier residents thanks to a long history of spatial segregation and the current expansion of gentrification into once marginalized neighbourhoods like East Austin. The overall municipal response to these challenges has been to densify, but this approach alone does not adequately address the socio-environmental conflicts that have shaped displacement, gentrification and the lack of affordable housing since the 1990s.

A green city for whom?

Perhaps the most noted environmental movement in Austin has been the Save Our Springs (SOS) alliance, which organized around the preservation of the city’s aquifers and successfully effected the 1992 Ordinance that limited urbanization in West Austin. But at the same time, East Austin residents led by the PODER grassroots environmental justice group mobilized for the successful removal of polluting industrial plants in the area. These collective struggles reflected a local environmental movement that by the 1990s differed greatly for White and non-White activists. While African Americans and Latinx residents forced into East Austin by the 1928 masterplan were responding to poor environmental conditions that threatened their health and wellbeing, the mostly White residents of west Austin enjoyed relatively healthy environments in addition to new greening from decades of watershed preservation efforts. Both of these struggles fueled governmental efforts to secure Austin’s reputation as a green and ‘livable’ city, a brand that has been harnessed by planners and public officials to attract new investment.

“R.L. waits for his ride to weekly dialysis in front of his home on East 12th Street, where rising rents are pushing out longtime residents.” Photo Julia Robinson via Texas Observer

And attract new investment it did: over the last three decades, the once university- and government-centered town has become a hotspot for tech industry companies whose wealthy employees pay high prices to access the city’s green and hip lifestyle. Yet, the benefits from these new developments have not been captured equitably. While the constraints on growth in west Austin brought by the SOS Ordinance and a 1990s Smart Growth initiative pushed real estate investment to the formerly industrial, low-income East Austin, the latter also became more attractive due to cheaper land, upzoning to higher density uses, industrial site clean-up, and the shutting down of polluting industries. As a result, East Austin’s Black and Latinx low-income residents—who fought for environmental improvements that were leveraged by boosters to support economic growth — are now facing a struggle to stay in their own neighbourhood.

This new paradigm of a more hip and more ecological city that is at once less equitable and less affordable to all but the highest paid workers presents a tough challenge that is anathema to the culture of Austin pre-1990; and this paradigm is ever more common across cities in the US and Europe. Today, Austin is a prototypical example of a city where a narrow ecological and economic view of the challenges faced by unbridled growth generates conflicts with goals for social justice and housing affordability. The pursuit of environmental preservation became license to push aside social challenges. Now East Austin has one of the highest levels of gentrification in the US and the city is struggling to retroactively enforce some basic assurances of social equity.

Major construction projects underway in 2018 around Austin’s old Seaholm power plant. Photo by Steve Ingenito

Plans for a denser Austin: green buildings and a new land development code

Since the early 2000s, both activists and the municipality have turned to urban densification as a solution to the lack of affordable housing that drives much of the inequitable outcomes produced by the legacy of green growth. That includes initiatives like Austin’s program for developing more green buildings, highlighted by institutions such as Foundation Communities, Austin Energy and the Office of Sustainability as a way to provide housing that is both ecological and affordable. But activists and community members, such as the Austin Neighborhood Council, argue that without substantial regulation and subsidy, these efforts will only fuel recent gentrification and reinforce environmental privilege.

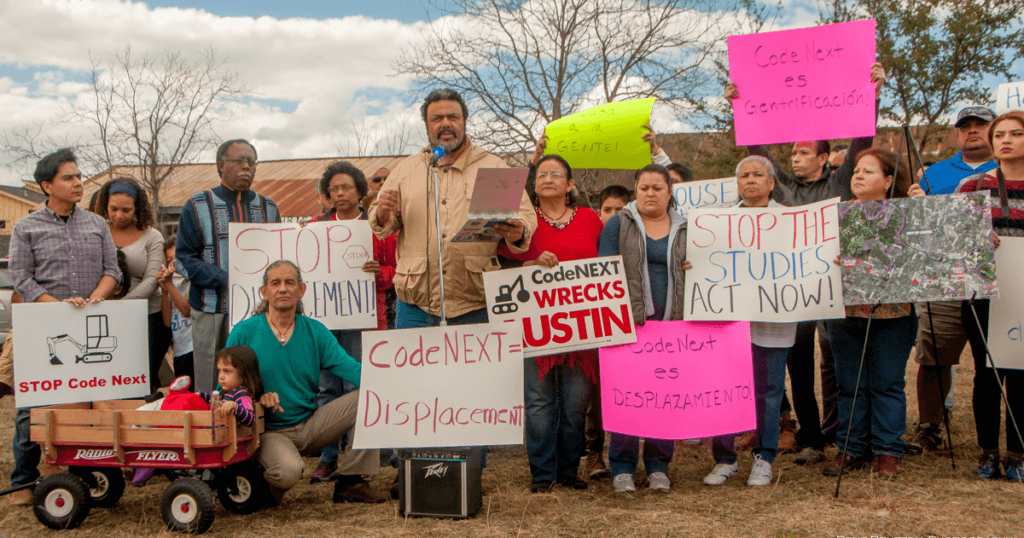

A crowd of neighborhood activists gathered in support of six detailed proposals that the Austin City Council can immediately adopt to fight the rampant gentrification and the displacement of local families in their communities. Photo via CNC

New zoning and land use initiatives pushing density included CODENEXT, an updated land development code elaborated in 2012 that sought to finally reconcile interests for more real estate investment, more affordability and continuing environmental preservation, but that initiative eventually died after it became clear that this goal was not being met. The resistance from a wide coalition of grassroots groups claimed that it would mostly benefit developers and perpetuate displacement in areas like East Austin. Now, in a new effort to strengthen the hand of social equity interests that were pushed aside, attempts are being made to revive the plan.

Social Justice: A new agenda for density

A newcomer organization led by young people of color, the Austin Justice Coalition, has stepped into the fray of the density debate to argue that any new land use policy cannot blindly push for increased growth on targeted areas — as has been the strategy in the past. Nor, they argue, do assertions that the market will produce affordability stand up in the context of Austin. Rather, the Coalition advocates for creating policy with a conscious and overt recognition of the historic racial inequities embedded in land use and development in the city.

Building on research from the University of Texas’s Uprooted Project, joint proposals by progressive city councilors and activists like the Austin Justice Coalition for an “equity overlay” to the land development code are gaining support. This would put additional affordability and multi-family protections in areas targeted for increased density that are also vulnerable to gentrification. There are also numerous other equity-oriented proposals coming out of the latest debates, but what matters most is that density initiatives are being pushed away from a narrow environmental or economic justification and toward direct engagement with questions of social justice that addresses the drivers of injustice in cities.

Beyond density: alternatives for equity and affordability

As affordability continues to be one of Austin’s most difficult challenges, the question remains: is density enough? Or is this more of what has already come?

What is particularly missing from the conversation is a willingness to seriously expand support for alternative housing models. Austin could learn from cities like Barcelona, which is experimenting with the city-sponsored implementation of housing cooperatives as a way of allowing for greater tenant protection and lower purchase costs, through collective management and ownership. Barcelona’s city council has been encouraging this model by designating public land for its construction. Additionally, housing cooperatives such as La Borda have been incorporating green building principles, allowing for housing provision that is both equitable and ecological.

Housing cooperative La Borda in Barcelona, designed by the architecture cooperative Lacol. Photo via Lacol

Community Land Trusts have also proved successful in various US cities as a way of maintaining security of tenure and guaranteeing fair housing prices. Similar to the housing cooperative model, residents collectively own the land where their houses are built, avoiding speculation and gentrification. While community land trusts and cooperatives exist in Austin, such alternatives have not been seriously incentivized through citywide policy.

If Austin wants to protect its residents from gentrification and displacement and remain both green and equitable, it cannot rely on the same system that put social and environmental goals at odds and generated deep social divides. It needs to go beyond mere increases in density, by implementing fair and non-speculative housing policies. Supported by initiatives like the equity overlay, city support of collective ownership could go a long way in this direction.

Featured image (top): “Recover and Discover” is the slogan for the so-called government-led revitalization of the East Austin district The picture shows a mural painted for a district festival in the East 12th Street Business Corridor, promoted by the Austin Revitalization Authority, Huston-Tillotson University and the city’s Economic Development Department. Photo by Ralph Barrera, American-Statesman

—

James Connolly is co-director of the Barcelona Lab for Urban Environmental Justice and Sustainability (BCNUEJ). He has a PhD in Urban Planning from Columbia University. His research explores how urban planning and policy serve as an arena for resolving social-ecological conflicts in cities.

Mateus Lira is a researcher at the Urban Transformation and Global Change Laboratory (TURBA), Universitat Oberta de Catalunya. He holds a dual MSc in International Cooperation in Urban Development from the Technische Universität Darmstadt and the Universitat Internacional de Catalunya. His current activist-research practice focuses on knowledge and learning within housing activism and collaborative housing initiatives.

One Comment