By Helen Cole

In South Park, the fight for environmental justice is giving way to an affordable housing crisis.

—

This post is the third in the Series “Green inequalities in the city”, developed in collaboration with the Green Inequalities blog, and which seeks to highlight new research and reflections on the linkages between the dominant forms of “green” redevelopments taking place in cities and questions of urban environmental justice, and the challenges and possibilities these imply for more just and ecological urban spaces. The series contributions will be published on the first and third Tuesday of each month.

—

Despite the widespread gentrification of Seattle, South Park has remained one of the city’s most affordable neighborhoods. In large part this is due to its status as a superfund site and its limited connectivity to other parts of the city. But like other communities across the US plagued by pollution and a history of environmental injustice, its recent cleanup and development of much-needed green space are spurring gentrification and inadvertently raising the cost of living. These improvements are a double-edged sword for many South Park residents, who wonder whether all those new parks are worth it if it means they can’t afford the rent. Can South Park be both green and affordable?

Located on the banks of the Duwamish River, South Park is a majority-minority neighborhood (in a city that is over two-thirds non-Hispanic white), that has experienced chronic underinvestment for decades. In compensation, various city departments are rolling out numerous initiatives including a safe streets project, the renovation of various green and public spaces, a proposed plaza at the base of the newly rebuilt 14th Ave bridge, and several long-overdue infrastructure improvements.

While its environmental challenges and relative isolation have to some extent “protected” the neighborhood from rising prices despite widespread gentrification in Seattle, the reopening of South Park’s 14th Avenue bridge in 2014 marked a significant change. In fact, despite the acute threats posed by things like poor air quality, flood risk or the lack of green space, most residents now cite gentrification—particularly rising housing costs and the threat of eviction—as the most urgent problem.

Industrial businesses line the Duwamish River, as seen from Duwamish Waterfront Park in South Park. Photo by Helen Cole.

Affordability versus greening

This growing fear has led to tension in the neighborhood around the fight to allocate resources towards affordable housing over greening projects. For example, many residents that oppose the new plaza at the 14th Avenue bridge feel that the land should be used to build affordable housing in response to the imminent threat of displacement posed by rising housing costs, rather than addressing the lack of green space or environmental deterioration that they have endured for years. This puts housing in direct competition with the environment, creating a trade-off that no resident should have to make.

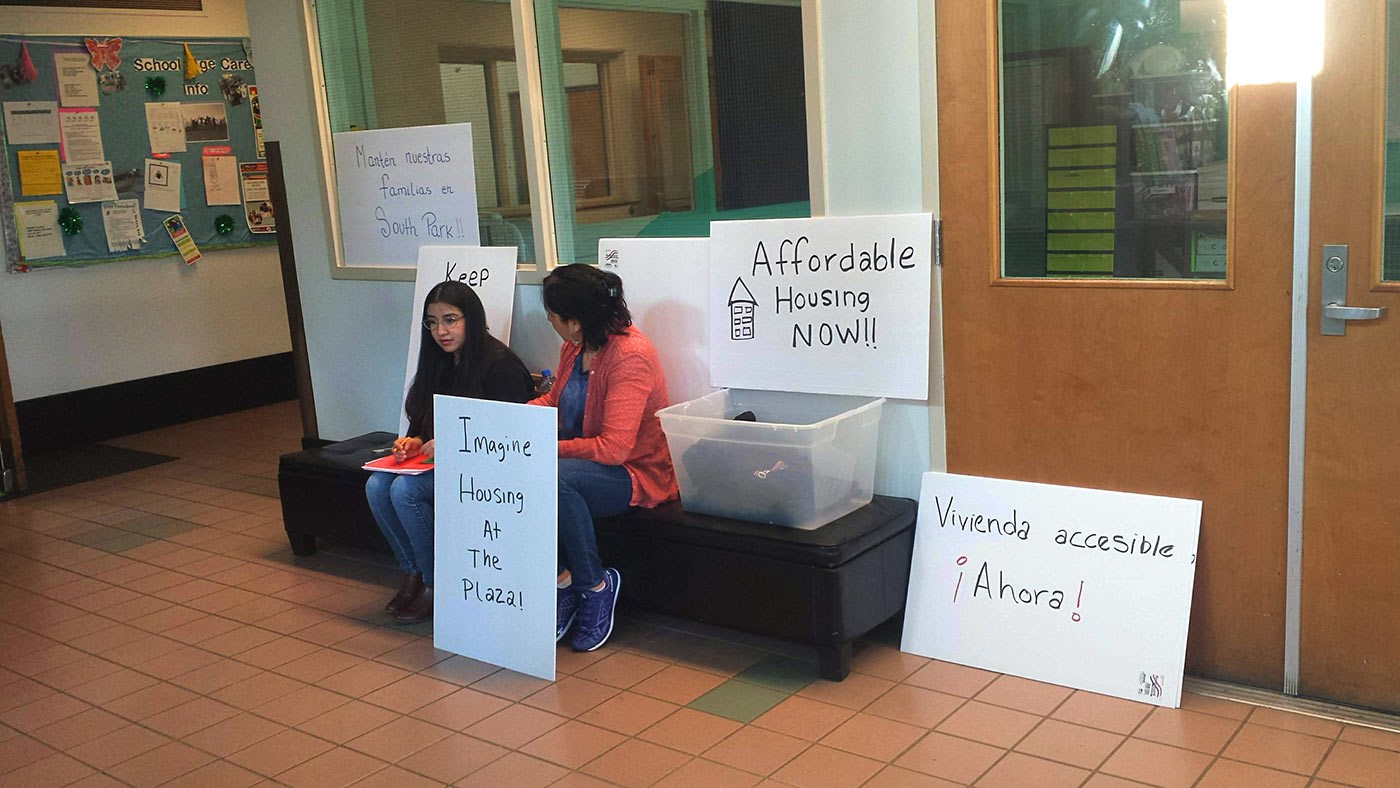

Activists at a neighborhood town hall meeting in South Park with Mayor Durkin. Photo by Helen Cole.

Availability and access to affordable housing

While residents see that the city is finally addressing its environmental concerns, they do not see any realistic efforts to address the issue of affordability. This was corroborated by the developers I spoke with during my field research. While the new Mandatory Affordable Housing (MHA) plan adopted in March 2019 requires new developments to either include affordable units or contribute to a citywide fund for affordable housing, many are doubtful. Due to the high price of land in the city, developers don’t find it economically profitable enough to pencil in affordable units. One developer told me that out of 16 multi-family projects they had worked on in the past few months, only one opted to include affordable housing in the design, which resulted in only one affordable unit.

Other important caveats are that the fund is not designated to a particular neighborhood, which means it will not necessarily benefit the neighborhoods where developers are building market rate housing, and the general process of getting things built is far slower than commercial construction. As a result, residents have little hope that affordable housing will catch up to the demand. Meanwhile, as luxury housing multiplies, so has homelessness, with a recent census registering a staggering 11,000 homeless persons in 2019.

In addition to the shortage of affordable housing, there is also unequal access to the little affordable housing that does exist. Among immigrant communities, barriers include language and limited access to the digital platforms where most offers are published and often taken before local residents even find out they exist.

Divisions also arise through the dynamics of informal networks. For example, many landowners/activists who own smaller properties and rent units at relatively affordable prices often seek tenants from similar social circles that tend to be white, limiting the opportunities for minority residents. Efforts at inclusion in general often stop at producing materials in Spanish, or offering interpreters for public events, addressing only some of the more obvious barriers to access.

Mayor Durkin addresses the South Park community as housing activists appear with signs demanding affordable housing. Photo by Helen Cole.

The role of greening in gentrification

In cities like Seattle, where there are very few affordable neighborhoods left, gentrification seems inevitable. During my field research, many residents that I spoke with said to have moved there in spite of its environmental problems, while others cited these same problems as a potential reason for leaving in the future. The city’s investment in addressing environmental issues may not necessarily trigger gentrification, but it may certainly speed up the process by attracting newcomers that would not otherwise choose a place like South Park.

Despite Seattle’s commitment to social and racial equity reflected in its initiatives and plans for neighborhoods like South Park, it is unclear whether gentrification processes thwart the efforts to achieve a more equitable city. South Park is a clear example of this dichotomous struggle towards a greener, healthier and more equitable neighborhood where lower and middle class residents can afford to remain as quality of life improves. That affordable housing should come at the expensive of other crucial environmental improvements needed in neighborhoods like South Park, is just one manifestation of the rise of green gentrification.

New housing in South Park. Photo by Hele Cole.

__

Helen Cole, a native of Arkansas, is a postdoctoral researcher with BCNUEJ focusing on the relationship between gentrification and health.

__

Top photo: South Lake Union, one of the most quickly developing neighborhoods in Seattle and the home of the Amazon headquarters, once an industrial area, was once proposed as a large central park which was contested by residents fearing the displacement of local businesses. Photo by Helen Cole.

Helen,

Your article does a great job elevate important community issues, and the untenable position of feeling that they need to choose between affordable housing and park. I want to also draw readers’ attention to the incredible work of the Duwamish Valley Affordable Housing Coalition, and efforts by the City of Seattle to address this issue. This is not a situation where either residents or city officials have thrown up their hands in resignation. Instead, it is an example, while not perfect, of how advocates on all sides can learn, and apply new models of equitable development. The Duwamish Valley Affordable Housing Coalition (DVAHC) and the Duwamish River Cleanup Coalition (DRCC) have worked with City of Seattle staff and electeds to identify resources for new affordable housing. The City’s Equitable Development Initiative has provided the DVAHC with $190,000 to build community capacity to advocate for and develop affordable housing, and may fund up to $1M towards the development of community-supportive spaces. The advocacy of DVAHC and DRCC complements the City’s racial equity initiatives, by helping the City learn how to translate citywide policies into place-based anti-displacement investments. In South Park, the community and City are working on multiple efforts to fund affordable housing, and the DVAHC is exploring the feasibility of using Equitable Development initiative grant funding to develop community-supportive spaces on another site on the Duwamish River. Over the coming years the City’s Duwamish Valley Program will support community conversation about how to address both economic and climate change displacement pressures, so the the incumbent residents and businesses can thrive in place.

https://www.seattle.gov/environment/equity-and-environment/duwamish-valley-program

https://www.seattle.gov/opcd/ongoing-initiatives/equitable-development-initiative