By Amanda Schockling

Houston’s reliance on the oil and gas industry leads to lower life spans in majority Black and Hispanic neighborhoods; a consequence of the historic redlining practices of the 1930s.

My neighborhood’s ZIP code played a big role in determining who I interacted with on a daily basis when growing up. As a child, my interactions were limited, and my social bubble restricted to who I met in school, around the neighborhood, and at my extracurricular activities. I attribute my childhood’s lack of diversity in part to my 5-digit postal code. The private school and Catholic church I attended in my ZIP code, as well as the kids I played with, were mostly white. And as a white person in Houston, I am no anomaly. White people are still more likely to be living among other white people than among African-Americans, Hispanics, or Asians in Houston, one of the most diverse cities in the U.S.

A lot of things depend on ZIP code in the U.S., just like the stamp says. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

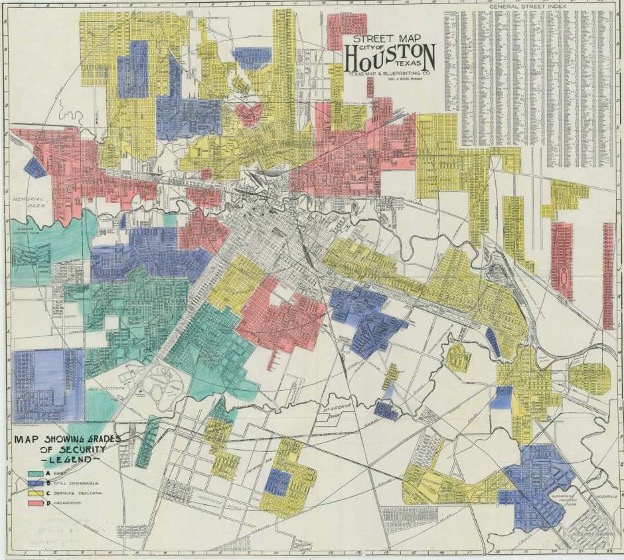

Houston is a sprawling, ethnically diverse city with a history of segregation and discrimination which continues to express today, due to the long-term effects of redlining and despite emancipation (1863) and desegregation efforts (1964). The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (a government-sponsored corporation created by the New Deal in 1933, which sought to expand housing options by refinancing loans and mortgages) drew the so-called ‘Residential Security Maps’, in 1933, after the Great Depression forced half of American households into loan default (Image 2). These maps, used by the Federal Housing Administration to administer loans, were drawn to indicate the desirability of neighborhoods largely on the basis of race. Blue and green neighborhoods were “desirable” areas to live, with the majority of residents of those areas being white. Yellow neighborhoods were marked as “definite declining” and those marked red were “hazardous”, singling out mainly Black populations, and hence the source of the term redlining.

An original map showing the redlining of Houston, Texas. Source: Houston Chronicle

Redlining was harmful for non-white neighborhoods across the U.S. because it was used as a risk warning to mortgage lenders and insurance providers. Many people were denied access to credit not because of poor qualifications but because of their ZIP code and race. Redlined neighborhoods “still suffer lower levels of investments than their white counterparts”. For example, research from 37 US cities showed that fewer trees were planted in redlined neighborhoods, resulting today in residents from such neighborhoods being more exposed to higher, and sometimes deadly, temperatures. This is a form of urban climate health injustice clearly marked by race. Other examples of “green inequalities” exist across the U.S. The City of Austin, for example, dedicates 15% of its land to green spaces which are more accessible to wealthier residents due to “a long history of spatial segregation and the current expansion of gentrification into once marginalized neighborhoods.”

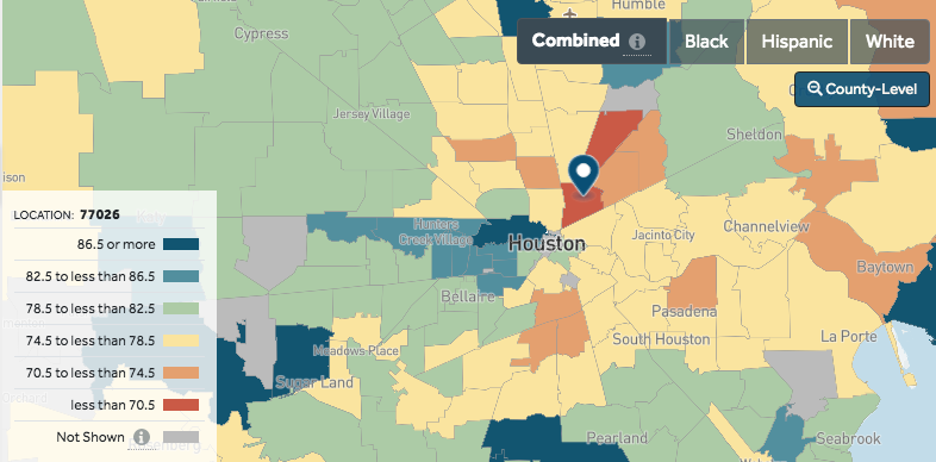

Moreover, redlining practices and Houston’s lack of zoning regulations regarding the different possible uses of land within the city, makes it easier for polluting industries to move in and harder for neighbors to move out. Today, the City’s oil refineries and chemical plants surrounding the Houston Ship Channel make it the second largest petrochemical complex in the world (Image 3). There is no coincidence that the surrounding East Houston neighborhoods are also home to more African-Americans and Hispanics than whites. No one wants to live next to chemical plants, and those who can afford to move out have long ago done so. The people who live there now have no other options and due to intersectional inequalities are mostly people of color, marking yet another kind of urban environmental injustice in Houston.

A view of the petrochemical facilities along the Houston Ship Channel with a view of downtown Houston in the background. Source: Texas State Historical Association

Living next to petrochemical facilities and businesses handling hazardous materials comes with high risks. Neighbors near the Ship Channel not only have to see the negative impacts on their natural environments, but they also often experience the effects themselves, in their own bodies. In 2014, 4,000 barrels of fuel oil were released into the Ship Channel after a barge accident. In 2019, 9,000 barrels of toxic chemicals spilled into the Channel and 20,000 barrels of chemicals, including benzene, caught fire in southeast Houston, burning for several days.

A study conducted in 2006 had already found higher levels of dangerous air pollutants in neighborhoods surrounding the Ship Channel. A 2007 study found that children living within 2 miles of the Ship Channel were 56% more likely to get childhood leukemia than those living more than 10 miles away. A 2019 research study found that white people living near the Ship Channel in Pasadena (ZIP code 77506) have a life expectancy of 66.7 years (the lowest in Houston). Similarly, Black people living near polluting industries and rail yards in the formerly redlined neighborhood Kashmere Gardens (ZIP code 77026) have a life expectancy of 67.7 years (Image 4). Well-off, white Houstonians, however, have the highest life expectancy in the Houston area (92.1 years in ZIP code 77007/Memorial neighborhood). The 25.4-year difference in life expectancy is a matter of race and wealth; an intersectional matter of many forms of exclusion that come together to affect health trajectories in Houston.

A map showing life expectancy by ZIP code in Houston, Texas with ZIP code 77026 (mostly Black residents) pinned. Source: Author-made map from Texas Health Maps.

Political ecology examines polluting activities and environmental injustice, like those seen in Houston over the past century, and seeks to explain the not-so-natural disasters in terms of political and economic dimensions, power structures, and social differences. The combination of the redlining of majority Black neighborhoods with the placement of petrochemical facilities, puts minorities living in East Houston at a higher risk of negative health outcomes relating to environmental pollution. People in these neighborhoods have fewer means to relocate because of their inability to access credit. As a result, their bodies and health suffer because of their own powerlessness to counteract environmental changes happening around them.

Our ZIP codes shouldn’t be the sole determinant of our health. Living in a place where we are more likely to get cancer based on where we attend school and sleep at night, is unjust and unethical. And yet, this is the reality for many minorities living in Houston. One might remark that I’m “lucky” to have grown up far from polluting industries, but I counter that it wasn’t a matter of luck. It was due to a history of racial capitalism and the politics accompanied with it, which stack the deck against racial minorities and which allow for the ‘sacrifice’ of underprivileged communities whose health and well-being is consistently devalued by industrial expansion and the economic growth brought with it.

Environmental justice activists, like Bryan Parras who founded Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services (TEJAS), lead the fight against permits, pipelines, and pollution in the Houston area by leading marches and “toxic tours” of the neighborhoods bordering the oil industry sites. Frontline organizations like the Southwest Workers Union and TEJAS recently called on local and state officials for a just recovery after February’s extreme cold left Texans on the brink of a complete power grid failure and Black, Latinx, Asian and other frontline communities the hardest hit. Students at Furr High School in Houston are educated on local environmental issues, collaborate with area organizations on hands-on projects, and are learning to advocate for themselves and their community in a reinvented, environmental justice-centered high school setting. Local communities know that intersectional solutions are needed to combat the entrenched environmental problems facing their communities; we just need to listen.

—

Amanda Schockling was born and raised in a suburb of Houston, Texas and is currently a student of the Environmental Studies and Sustainability Science (LUMES) program at Lund University in Sweden. She is currently writing her master’s thesis on the Sunrise Movement and the emerging socio-environmental movement in the United States.

Featured image by: Houston Chronicle, available here:https://www.hereinhouston.org/env-justice.