By Gustavo García-López, Irene Leonardelli and Emanuele Fantini

A new open Series co-organized by the Undisciplined Environments and FLOWs blogs looks at struggles over more just and ecological water presents and futures.

Water connects every aspect of life: from our literal physical sustenance, to economic activities and political regimes. Within and beyond the current Coronavirus pandemic, a water crisis looms large. While media, government and NGO attention has almost entirely centered on the deaths caused by this pandemic, it can be easy to forget that globally, every 2 minutes a child dies from diseases caused by lack of access to clean water and sanitation. While worldwide one of the most common guidelines to prevent the spread of the virus has been to wash hands regularly and carefully, this is simply not possible for the 780 million people who do not have access to a safe water source.

Political ecologists have made important contributions to understanding this crisis. They have highlighted that the crisis is not one of ‘scarcity’ in the purely physical sense of lack of enough water, but rather, of the political-economic or hydro-social arrangements that govern how water is defined, valued, claimed, accessed, distributed and used. Scholars and activists have shown that the main forces contributing to this water crisis include: over-extraction and pollution (for urbanization, agriculture, mining, energy production and other industrial activities); restrictions in access and inequitable distribution due to neoliberal policies of privatisation and commercialization of water, and changing climatic patterns. Moreover, this water crisis most often (re-)produces spaces of privilege and marginality along lines of gender, class, ethnicity, caste, among other aspects of social difference. We could thus say that flows of water and their transformations are connected to flows of power.

Automatic Water Dispenser in Maharashtra, India. Source: Irene Leonardelli

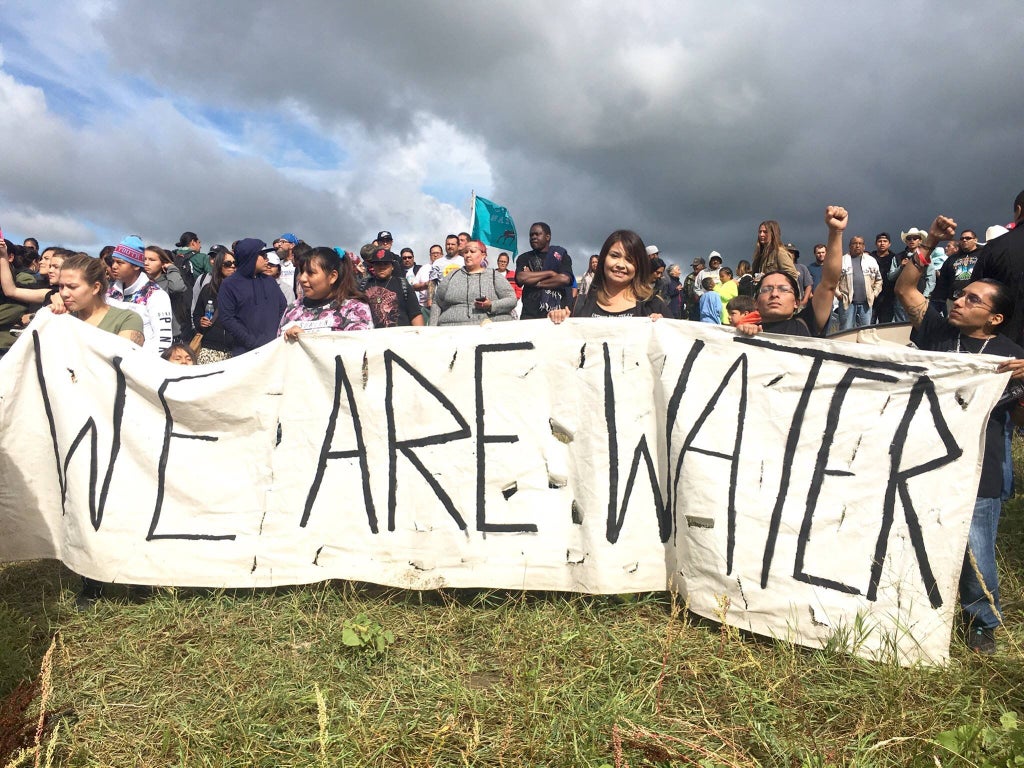

A key aspect of these “hydropolitics” has been the re-imagining and reclaiming of alternatives to the neoliberal extractivist model of water. Often these are summed up in geographer Karen Bakker’s dichotomy of “the commons versus the commodity”, pitted in a global “water war”. This conception of commons reflects ideas about democratic communal and/or public management, and the human right to water. The Movements across the world, from Italy and across Europe, to Bolivia, South Africa and the Dakota indigenous nation in the United States, have mobilized the discourse and practices of the commons in fighting water privatization, commodification and extractivist projects.

There is more to these binaries, for water commons (and commons in general) are not static; rather, people relate to water in different ways that evolve over time, and that can be contradictory in practice. Thus, the meanings of the concept of the common (as of privatization) are diverse and contested, involving always political questions about what is to be ‘common’, by/for whom (what community), and how (for what uses, through what decision-making processes). As Orla O’Donovan reminds us, the meanings of water are similarly manifold, ranging from a resource available for human use or commercial exploitation, to “a quintessentially communal substance flowing between and connecting our watery human and non-human bodies”. These emerging perspectives suggest a need for new ways of “imagining and doing water politics” , that begin to heal our destructive and unjust relations with it. These new ways demand a “re-membering”, in a double sense: bearing in mind the importance of water and past ways of relating to it, and a re-connecting of the ‘members’ of our water bodies. This can be understood through the term commoning, a process of re-making water commons that include different actors, both humans and non-human others and ways of knowing–that is, to reimagine, remember, and reclaim our interdependent connections to each other and to water.

Session organized by the Our Water Commons collaborative program (part of the On the Commons organization) in the 2002 World Water Forum in Istanbul. From left to right: Adriana Marquisio, President Uruguay’s Public Water Workers Union; Maude Barlow, former Senior Advisor on Water to the UN General Assembly President; Uruguayan Minister of Environment; Daniel Moss, Coordinator of Our Water Commons. Source: Our Water Commons.

Building on these emergent discussions and activist practices, this Series seeks to highlight critical thinking on current challenges and possibilities for more just and ecological water presents and futures. In contrast to dominant perspectives on water governance which focus on economic and technical aspects and institutionalized forms of collaboration, we heed calls for re-centering ‘the political’ in water decision-making, use and management. The series emerges out of a collaboration between Undisciplined Environments and the FLOWs blog from the Water Governance Department at IHE Delft Institute for Water Education, and will be published jointly on both blogs on the third Tuesday of every month. Some of the topics which will be covered include the integration of indigenous peoples rights into international water governance frameworks, the relation between gender and water governance, struggles for water justice in the context of conflicts against extractive projects such as mining, hydropower and water transfers, and the scaling-up of grassroots alternatives to this water extractivism. The series is open-ended and we would be happy to receive ideas for contributions from engaged scholars and activists to re-imagine, re-member and re-claim water commons.

—

Gustavo García-López ([email protected]) is Assistant Researcher at the Center for Social Studies, University of Coimbra, and the 2019-2021 Prince Claus Chair in Development and Equity at the International Institute of Social Studies, The Hague. He is a member of the Undisciplined Environments editorial collective.

Irene Leonardelli ([email protected]) is a PhD student in Feminist Political Ecology at the IHE Delft Institute for Water Education, in the Netherlands, and part of the WEGO-ITN and has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 764908. Her research focuses on processes of agrarian transformation and water governance in Maharashtra from a feminist perspective. She is a member of the Undisciplined Environments editorial collective.

Emanuele Fantini ([email protected]) is Senior Lecturer / Researcher in Water Politics and Communication in the Water Governance Department at IHE Delft. He is the editor of IHE Delft Water Governance blog, FLOWs, and he hosts the podcasts “The sources of the Nile” and “Water Alternatives Podcast”.

Top (feature) image: Dakota Access pipeline protesters at Cannonball River in North Dakota. Understandings of water based on its interconnectedness to humans and all life is central to many grassroots water struggles. Source: No Dakota Access in Treaty Territory – Camp of the Sacred Stones (Facebook page).

17 Comments