By Margarita Triguero-Mas

If equity is not made a priority, Cleveland’s vision of becoming a “green city on a blue lake” risks falling victim to the injustices of green gentrification felt in similar revival cities across the US.

Editors’ note: This post forms part of the series “Green inequalities in the city”, developed in collaboration with the Green Inequalities blog. The series seeks to highlight new research and reflections on the linkages between the dominant forms of “green” redevelopments taking place in cities and questions of urban environmental justice, and the challenges and possibilities these imply for more just and ecological urban spaces.

After decades of economic decline and environmental degradation, the city of Cleveland, Ohio is experiencing a mild renaissance through greening and other revitalization efforts. Yet, by catering to and benefitting mostly wealthier, white residents, some environmental amenities seem to be perpetuating long-standing racial inequalities. Can a majority African-American post-industrial, recovering city like Cleveland address its historic environmental inequities without reproducing the negative effects of environmental gentrification observed in so many other cities? A comparative of projects in the Detroit Shoreway neighborhood may give us some clues on how community-focused green developments might avoid the onset of green gentrification.

Cleveland’s decadence and renaissance

Cleveland’s rapid decline began in the 1950s and accelerated during the 1970s when massive population loss due to industrial restructuring (and the consequent loss of jobs) and residents moving to the suburbs. This process left thousands of vacant houses and lots in its wake. Over the next few decades, Cleveland’s notoriously polluted Cuyhoga River also had devastating impacts on health that, like other epidemics, predominantly affected low-income and Black residents. Particularly over the last ten years, the river’s restoration and clean-up—as part of a concerted effort to re-brand Cleveland as “a green city on a blue lake”—has significantly changed the course of its urban development.

Ethnically-diverse neighborhoods which have been subject to are scheduled to undergo green revitalization, such as Tremont, Ohio City and Detroit Shoreway, have experienced a resurgence in the form of gentrification. Despite its negative associations, during our GREENLULUS’s project qualitative fieldwork many residents have described this as a desirable dynamic after so many decades of decline. In contrast, some local stakeholders say that other parts of the city, like the predominantly-Black East Cleveland, are apparently “too poor” or “too Black” to be gentrified.

But is gentrification and its associated racial inequities an inevitable consequence of (green) development? Perhaps we can find some answers by comparing two dramatically different green developments located in Detroit Shoreway neighborhood.

Revitalization and Greening in Detroit Shoreway neighborhood

Detroit Shoreway is a majority white caucasian neighborhood, with a relatively high population of Blacks and Hispanics. While the racial diversity of the neighborhood is often cited as a major asset, economic disparity is a reality too. Moreover, the greening-related developments of the neighborhood are far from homogenous.

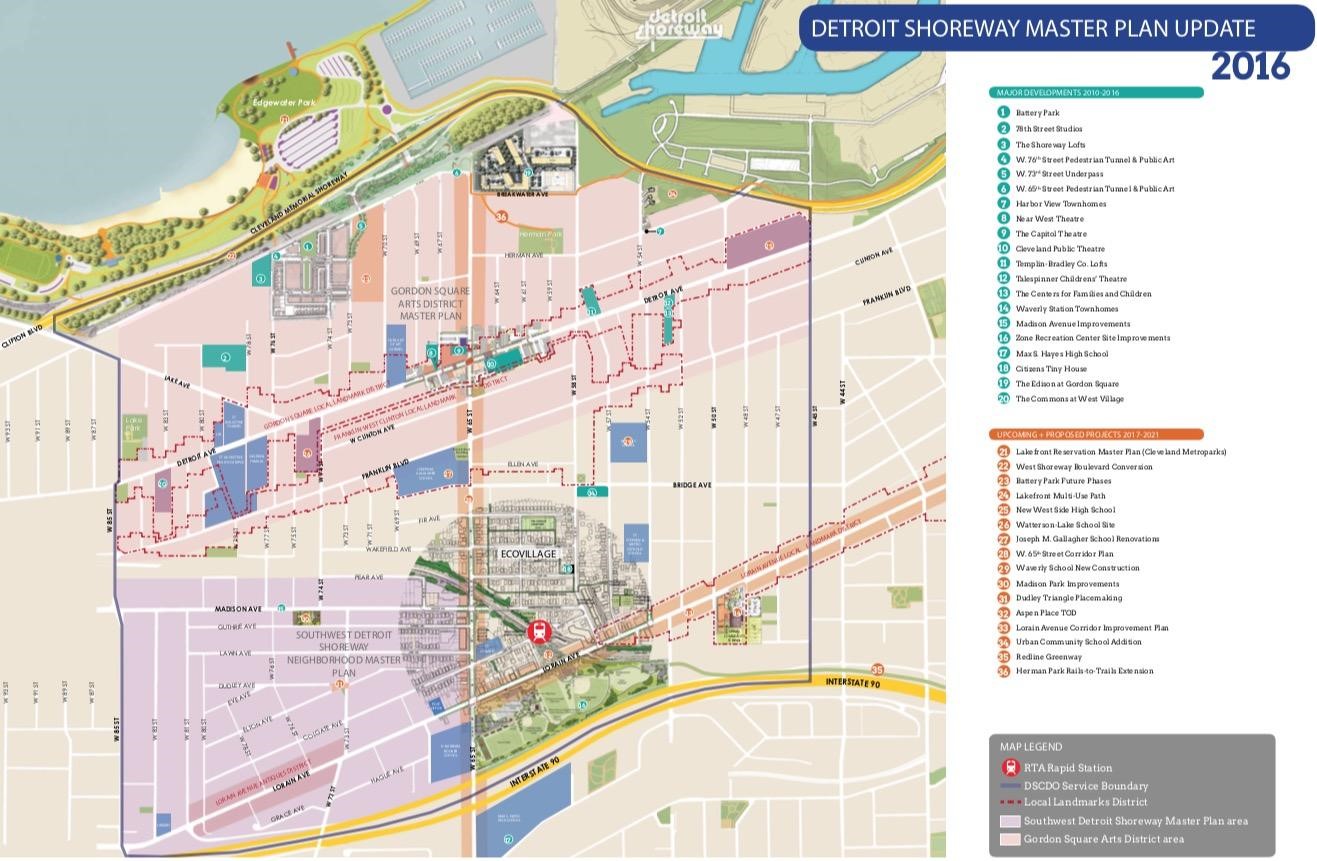

Detroit Shoreway neighborhood Master Plan. The map shows the borders of the neighborhood, with most new luxury developments to the north and EcoVillage in the southeast. The map also shows some of the main greenspaces, giving an idea of the potential influence of Edgewater park on the neighborhood development.

In the northern section of Detroit Shoreway, a post-industrial area historically home to many Italian immigrants, the new Gordon Square Art District has spawned an array of cultural and gastronomic offers. The area has also recently seen new luxury housing next to the restored Edgewater Park. The park, once riddled with crime, is now one of the city’s main attractions, complete with lakeside beaches, boat ramps, a fishing pier, picnic areas and a beach house with food trucks and live events.

Residents enjoy open-air barbecues along the eastern part of Edgewater Park. Source: Author

Life in Edgewater Park beach. Source: Author.

The role of environmental amenities like Edgewater Park in bringing investment and new residents to the neighborhood is perceived as secondary by most respondents of our interviews with residents. Factors like proximity to downtown and motorized high-speed roads, and the new availability of sit-down restaurants, are the factors that most interviewees identified as shaping the attractiveness of Detroit Shoreway for newcomers. However, for-profit developers highlight and use as a selling and marketing point Edgewater park as a core attraction of the neighborhood.

For whatever reasons, it is undeniable that this northern area mostly attracts wealthy white couples and detracts long-time residents due to their lower purchasing power. Moreover, its popularity is in one way or another affecting all Detroit Shoreway neighborhood residents. Many of those we interviewed explained how close friends and family have not been able to find a home they can afford and how they have felt socially displaced from certain areas.

Billboard for a new development in the Detroit Shoreway neighbourhood (May 2019). Source: Author.

A contrasting example of green redevelopment is the EcoVillage project the southeast section of Detroit Shoreway. EcoVillage is a pedestrian-friendly, Transport Orientated Development (TOD) dating back to 1996 that was designed to promote social integration and sustainability . The homes in the area have access to a large urban park with walking paths, playgrounds and outdoor and indoor sport fields like the Michael J. Zone Recreation Centre. Residents also have access to a train station and bus lines that allow them to easily reach their workplaces within 20-40 minutes. Despite having attracted mostly white middle-income residents, EcoVillage has been quite successful in keeping its existing Black and low- and middle-income residents and in avoiding any major cultural, social or physical displacement.

So far, EcoVillage does not seem to be contributing to any gentrification processes. One of the successes of this project may lie in its deliberate inclusion of the less privileged, focusing on filling empty lots and not making changes to existing homes. It envisions a heterogenous community in terms of education, class, ethnic background, income and access to capital. Still, some argue that the particular success of Detroit Shoreway’s EcoVillage may be attributed more to the constraints on new investments imposed by the 2008 global financial crisis than to its inclusivity measures.

A view of an EcoVillage home southeast Detroit Shoreway (May 2019). Source: Author.

Yet, Detroit Shoreway’s EcoVillage is an exception to the rule when it comes to ecovillages in the Global North, which are mostly inhabited by white, upper-middle class, highly educated residents and where the high cost of living is an impediment for inclusion. In fact, the role of ecovillages in fighting social inequities is controversial. While social justice is recognized as an essential factor for sustainability, it is not the central aim of most ecovillages.

Civic and policy efforts to avoid displacement

In light of challenges like these, Cleveland is discussing policies to avoid displacement and ways to achieve racial equity. In addition to educational initiatives like organizing exhibitions and trainings on structural and institutional racism, the newly-created Equitable Community Development Strategy of Cleveland has launched a call for proposals to explore how existing policy can protect current long-term residents from displacement while promoting development and taking into account differences between neighborhoods and a broad range of factors like transit and jobs.

The question is now whether recent conversations and initiatives around development and equity will bring actions quickly enough to make sure that the vision of Cleveland as a ‘green city on a blue lake’ does not perpetuate and exacerbate existing racial and social inequities as it transforms from a recovering and shrinking industrial city to a metropolis with a more diverse economic base.

There is indeed a risk that Cleveland follows the path of revival cities such as Philadelphia or Washington DC where the rates of redevelopment and gentrification-driven displacement are today some of the highest in the country. Cities must find ways to tame green gentrification resulting from new green developments while also ensuring that sustainable projects like the Detroit Shoreway EcoVillage do not become drivers of gentrification themselves and can be inspiring other similar initiatives elsewhere in the city and beyond.