Hydropower projects, disguised and depoliticized as green and sustainable, are being imposed as a development solution across the Himalayas. The dam conflicts presented here illustrate how civil society groups have become political actors, rising up against assaults on democracy.*

Source: NHPC.

Source: NHPC.

Climate change has set an imperative for economies around the world to revise their development models in recent decades, towards more sustainable and ‘carbon-neutral’ energy production. This is also opening up new spaces for capitalist development to exploit.

Often, new profitable technologies are promoted as green and ecologically sustainable, while accompanying environmentally and socially destructive processes are obscured. This process is commonly known as ‘greenwashing’, and large hydropower dams make for a great example of this form of depoliticization.

Hydropower has long been promoted as a clean energy technology by governments, donor agencies, private sector companies and even big green organizations across the globe. These promotions have persisted despite the negative impacts of hydropower dams on people and the environment, exposed by civil society campaigns since the 1980s. By the 1990s the World Bank, largest international hydro-financier, had withdrawn most of its support for dam construction.

Yet as climate change policies tend to celebrate hydro as a clean and green energy model, the large dam has made a comeback. What is being largely overlooked in the process – deliberately or not – is that social and environmental impacts are still controversial, and that dam construction practices are rather dubious.

The biodiversity and landscapes in the footprint of large dams are often home to indigenous and/or agricultural societies who claim rights to these territories as their ecological, ancestral and spiritual commons. Their way of valuing nature – i.e. as invaluable heritage, mother nature or abode of gods – is radically incompatible with that of hydropower proponents, who only see a commodity.

Thus, as with many other ‘green’ technologies, in addition to depoliticizing ‘greenwashing’ discourses they are often accompanied by fundamentally undemocratic means of governance. This may include the deployment of exceptional laws or the repression of democratic and fundamental human rights through state actors and armed forces.

Buddhist monks and activists protesting against construction of the Rathong Chu hydropower project in Sikkim in the 1990s. Source: SIBLAC / indiatogether.org.

Hydropower development in the Eastern Himalayas

In India, the revival of large dams has led to a sudden expansion of hydropower development activities in the Eastern Himalayan border region in the Northeast of the country, known as India’s “water towers” and the nation’s last untouched hydropower ‘frontier’. Between 2003 and 2010, the governments of the two states Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim signed over 160 agreements for hydropower projects, mostly with private companies.

The capitalist relations underpinning these hydro ventures are evident, as private developers anticipate huge profits and ample opportunities for financial speculation in the stock market. Local political elites, in turn, are benefiting by way of kickbacks. The state earns 12% of the power or revenue generated for a period of 35 years, after which it becomes the owner of the project. The communities whose land is acquired for dam construction are entitled to only 1% each from the state and the power developer for ‘local area development’.

For downstream areas or other areas adversely affected by the project, where land has not been acquired, there are no compensation or rehabilitation provisions. In the long term, the purchased agricultural and forest land is effectively transferred from private and community ownership to the state. As such, hydropower development represents a form of enclosure of the commons (river, land, forest) for purposes of capital accumulation.

By 2010 Arunachal Pradesh had awarded contracts for construction of 130 large hydropower projects on all of its rivers, mostly to private companies. The figure has risen to around 170 since then. Source: The Economic Times.

In Sikkim plans for around 30 run-of-the-river projects will leave virtually no stretch of the Teesta and Rangit rivers flowing free. Source: Vagholikar and Das, 2010.

Hydropower contradictions and challenges to democracy

The commodification of the Eastern Himalayan Rivers is legitimized as the only way in which these peripheral states can generate revenue, become financially independent and enhance local development. Since this is a less-developed mountain region with serious infrastructure deficiencies – particularly for transport, electricity and health care provision – the discourse of development is used as justification for the construction of dams. Dam enthusiasts also claim that projects serve the national interest. Finally, by labelling the projects “run-of-the-river”, a technology which is neither supposed to affect the flow of the river nor to cause significant submergence and displacement, promoters claim that these dams are low impact.

Reality, however, tells a different story. Existing projects are diverting almost the entire river flow through underground tunnels that can reach up to 20km long, dug by blasting. Communities on the land above the tunnels experience declining availability of water sources, lowered groundwater tables and degraded land. This affects agricultural production and residential buildings and can lead to displacement even after project completion.

It also creates anxieties about potential future impacts, including from projects yet to be implemented. What will happen, for example, if a flash flood or an earthquake damages a dam upstream? Could it cause a domino effect? And how will the arrival of hundreds or thousands of workers from other parts of the country impact local cultures, politics and economies?

The choice for hydro-based development is a political choice that calls for public debate and negotiation, involving all concerned actors, yet the process to date has been anything but democratic, inclusive or participatory.

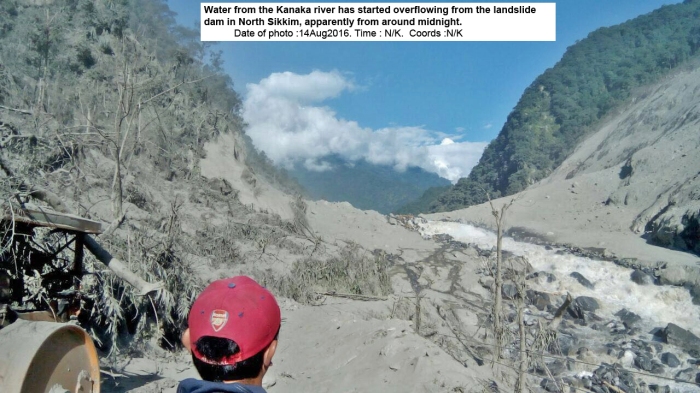

Only last week, on 13 August 2016, a landslide dangerously blocked the course of a river in Dzongu, North Sikkim, roughly 20km upstream from the 510 MW Teesta V hydroelectric project. If the landslide dam fails it could unleash a flash flood similarly destructive as the one in Uttarakhand in 2013. Source: Save the Hills.

Depoliticization through discourse and state-sanctioned illegality

In publicizing and promoting projects, uncomfortable facts oftentimes remain untold or understated. For example, that underground tunnelling impacts the land and water resources above; or that a barrage is able to dam and store water even though its technical design is different from a dam. Instead of clarifying and accounting for inconveniences and technicalities with unpleasant consequences, government and company representatives often share one-sided information about projects to appease affected communities with promises of employment, local infrastructure development and free electricity. This is a form of depoliticization, undermining public debate and democracy.

To the local populations it becomes evident only at the stage of construction, or even only after project completion, that employment opportunities tend to diminish with the completion of construction activities; that promised health, education and communications facilities often do not materialize or do not meet locally specific needs; or that the promised electricity is not for free after all, and can only flow if transmission lines are installed. The market town of Dikchu near the 510MW Teesta V hydroelectric project in Sikkim has been facing several hour-long power cuts almost daily several years after project completion.

The 97MW Tashiding project in West Sikkim is one example where public consultation and the eliciting of consent were largely sidestepped. The mandatory public hearing was so poorly advertised that many locals thought it never took place. Despite a stay order issued in 2012 because mandatory approval by the National Board of Wildlife had not been obtained, construction works continued and millions of rupees have been invested since.

Construction works for the 97MW Tashiding hydropower project in West Sikkim, April 2015. Source: author.

Suppressing democratic freedoms

Where communities stand up to contest hydropower development and the procedural injustices it is fraught with, they face heavy-handed responses by the state. One common way of suppressing dissenting voices is by cutting off so-called ‘benefits’ to the concerned persons and/or their families. In Sikkim, teachers in particular have been ‘punished’ through transfers to new assignments across the state, including to remote locations.

In the Dibang Valley of Arunachal Pradesh, civil society groups and dam-affected people successfully blocked the mandatory public hearing for the 3000MW Dibang Multipurpose Project for six years. In response, the state government mobilized paramilitary forces, which resulted in violent clashes. In one incident the police fired at a group of students during a religious celebration. This heightened fears and the activists eventually resigned, permitting the public hearing and confining their demands to improved terms of compensation. Other incidents of violence (state-mediated or otherwise) against dam critics in Arunachal Pradesh include the recent killings of two protesters in the Tawang district, and the shooting of an outspoken female journalist in 2012, amongst others.

Members of the indigenous Idu Mishmi community blocking the road in protest against the Dibang dam project. Source: sandrp.wordpress.com.

Reclaiming democracy

Citizen groups who contest hydropower plans in the Eastern Himalayas undoubtedly face formidable obstacles: local civil society and affected communities often lack the political self-determination and experience to mobilize against the state or the private sector. Due to the greater political and economic power of the latter, many people fear being targeted and economically marginalized. The Himalayan geographic and cultural landscape also makes it difficult to mobilize across natural and ethnic-cultural boundaries. Different ethnic groups often compete against one another for the resources and opportunities provided by the state, and are therefore reluctant to cooperate. Other times they are simply too far apart. Nevertheless different anti-hydro movements have emerged and have challenged project proponents – in context-specific, strategic ways.

(Re-)claiming identity

In North Sikkim a group of indigenous Lepcha activists – the Affected Citizens of Teesta (ACT) – staged one of the earliest examples of resistance against hydropower development. Several years of street protests, protracted hunger strikes and persistent legal activism have culminated in the scrapping of four out of seven proposed projects within the ‘tribal reserve’ Dzongu. Two projects are still being challenged in the courts.

As a major mobilizing tool, ACT used and ‘re-invented’ their distinctive identity: a ‘vanishing’, endangered tribe. Arguably, this issue had more traction with the government because the ruling party had won its votes by promoting an all-inclusive policy centred on enhancing the political recognition and protection of minority communities. It was also a way of redefining a sense of cultural self-esteem and political emancipation, and helped mobilize larger numbers of supporters from the Lepcha community, which had been split over the issue of hydropower.

ACT activists during a protest against dams in Dzongu. Source: saveteesta.wordpress.com.

Mobilizing for inclusive governance

Members of the indigenous Adi community in Arunachal Pradesh are staging another on-going struggle for self-determination. Their main contention is that dam construction on the Siang River will submerge the majority of wet-rice fields on the river banks, an important asset in the Adis’ subsistence economy, and a marker of culture, identity and political autonomy.

The Adis take collective decisions through traditional democratically organized community councils (one vote per household), and these are binding for all community members. This allowed civil society activists to mobilize a unified, resolute political stand against three large dam projects planned on the Siang River (even if individual opinions may differ), and a resolve not to allow any project activity before public consultations are held. Their adamant refusal to allow the mandatory public hearings has so far discouraged project proponents to further pursue project plans.

The Siang Valley, Arunachal Pradesh. Source: SANDRP.

Politicizing new issues

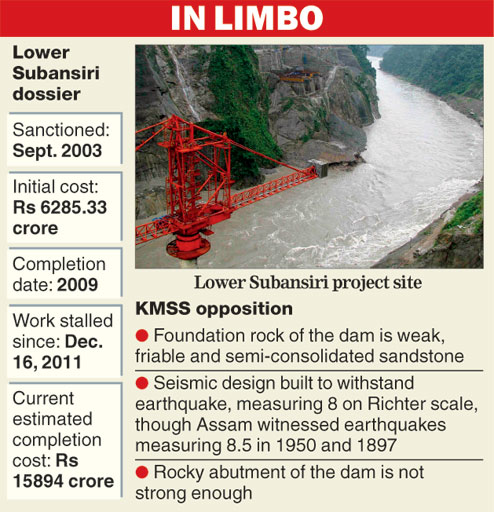

The most powerful resistance to hydropower, in terms of numbers, is currently being staged by peasant and student organisations in the state Assam. The Assam anti-dam movement initially started mobilizing due to the failure of impact assessments and rehabilitation processes to account for downstream affected populations – a common shortcoming of hydropower governance. The 2000MW Lower Subansiri hydroelectric project, built on the Arunachal-Assam border, is expected to have significant impacts on Assam’s peasant economy, as flow fluctuations and potential floods resulting from the dam stand to disrupt agriculture, fisheries and transportation in downstream areas.

The movement has also tackled the rarely discussed issue of dam safety. Commonly perceived as a techno-scientific matter to be assessed by experts and scientists, dam safety concerns are often brushed aside by depoliticizing claims that today’s dams are technologically advanced, unbreakable and indisputably safe. A team of local academics demonstrated that this was not the case. They assessed and questioned the project’s site selection and technical design in light of the high risk of earthquakes, associated landslides, and possible disaster should an earthquake or flash flood hit the reservoir.

The anti-dam activists quickly picked up the issue and made it a central point of their campaign, for which they received backing from large sections of Assamese society. The Lower Subansiri project has become such a politicized issue that construction has been brought to a standstill for nearly five years (helped by the movement’s blockade of the supply of construction materials), and remains unresolved even after multiple rounds of high-level negotiations.

Source: The Telegraph India, 5 January 2015.

Lessons learned

This contribution outlines how democratic values and practices are being threatened by top-down hydropower planning, disguised as a green, sustainable and imperative development solution. The dam conflicts presented here illustrate how civil society groups have reacted to such assaults on democracy: by reclaiming their political identities; by mobilizing traditional democratic institutions to create a more powerful voice and by broaching and politicizing contentious issues that have previously been sidelined. Just as depoliticization can occur through very different means, it is important to keep in mind that there are myriad ways to counter it, depending on local experiences, political configurations, geographic characteristics etc.

To further enhance the democratisation of ‘green’ development it is important to rethink grassroots actors as political actors, and public action for social and environmental justice as an exercise of political agency. The political should be understood here not in the narrow sense of electoral politics, but as a way of starting or entering a public debate, of reclaiming voice and of laying open controversies and antagonisms through a range of strategies including civil disobedience.

* This post is part of a series sharing chapters from the edited volume Political Ecology for Civil Society. Amelie Huber’s contribution is included in the chapter on “Democracy”. We are eager to receive comments from readers and especially from activists and civil actors themselves, on how this work could be improved, both in terms of useful content, richness of examples, format, presentation and overall accessibility.

Futher readings

- Ahlers, R., et. al, 2015. Framing hydropower as green energy: Assessing drivers, risks and tensions in the Eastern Himalayas. Earth Systems Dynamics. 6, 195- 204.

- Baruah, S., 2012. Whose river is it anyway? Political economy of hydropower in the Eastern Eastern Himalayas. Economic and Political Weekly. 47(29), 41–52.

- Ete, M., 2014. Hydropower Development in Arunachal Pradesh: A new narrative in natural resource politics? Heinrich Böll Stiftung, India, 10 November 2014.

- Huber, A., Joshi, D., 2015. Hydropower, Anti-Politics, and the Opening of New Political Spaces in the Eastern Himalayas. World Development 76: 13-25.

- Imhof, A., Lanza, G. R., 2010. Greenwashing Hydropower. World Watch Magazine. 23(1).

- Meyer, K., et. al., 2014. Green and Clean? Hydropower between Low-carbon and High Social and Environmental Impacts. Briefing Paper 10, Deutsches Institut für Entwicklung.

- Vagholikar, N., Das, P., J., 2010. Damming Northeast India. Kalpavriksh, Aaranyak, & Action Aid India, Pune, Guwahati, New Delhi.

Civil Society organizations working on hydropower conflicts

- Affected Citizens of Teesta

- Carbon Market Watch

- Forum for Policy Dialogue on Water Conflicts in India

- International Rivers

- Kalpavriksh Environmental Action Group

- Legal Initiative for Forest and Environment (LIFE)

- Save the Teesta / Save Dzongu

- South Asia Network of Dams, Rivers and People

One Comment