By Emilie Dupuits

The second post of series “Reimagining, remembering, and reclaiming water: From extractivism to commoning” , co-organized by the Undisciplined Environments and FLOWs blogs, discusses controversies and challenges in scaling-up social struggles for water conservation and sustainable livelihoods in the Intag Valley, Ecuador.

The evolution of the anti-extractivism struggle in Intag Valley

The “Citizen Revolution” government of Rafael Correa, in power between 2007 and 2017, marked a considerable growth of mining investments in Ecuador and the exacerbation of social-environmental conflicts, often related to water resources. These investments were part of the extractivist policies implemented in the Latin American region by so-called ‘post-neoliberal governments’, which framed mining as socially and environmentally responsible. However, these policies contradicted the Good Living (Buen Vivir) and Rights of Nature principles recognised in the Ecuadorian Constitution of 2008.

The Intag Valley, located in the northern highlands of Ecuador, illustrates the multiplication of social struggles against mining and for the conservation of water resources in the country; as well as the development and scaling-up of concrete alternatives to extractivist projects. Several transnational companies have tried in vain to initiate mining explorations in the region. In the 1990s, the Japanese company Bishi Metals, and then the Canadian companies Copper Mesa and CODELCO (Corporación Nacional del Cobre de Chile), faced strong grassroots resistance. Several non-governmental organisations (NGOs), such as DECOIN (Defensa y Conservación Ecológica de Intag) and Acción Ecológica, as well as the municipality of Cotacachi, played a central role in opposing extractivist projects, by declaring Cotacachi “ecological canton” in 2000.

Beyond traditional resistance, various territorial alternatives to extractivism have emerged in the region. Territorial alternatives refer to the emergence of productive activities from the grassroots that contribute to improve local livelihoods while conserving the environment. For example, DECOIN invested in the conformation of community water reserves and in the development of agro-ecological activities, such as the production of organic coffee or ecotourism, which have contributed to unify an anti-mining front. In 1999, DECOIN acquired for the first time land in the community of Junin, threatened by mining exploration. In addition, a coalition of nine grassroots organisations including DECOIN created the Consorcio Toisan in 2005 to support the territorial alternatives of Intag.

Despite resistance, the government made an alliance in 2012 between the National Mining Company of Ecuador (ENAMI) and CODELCO in order to reactivate the exploration project of Llurimagua in the community of Junin. The grassroots organisations in the region responded to these threats by scaling-up their territorial alternatives through multi-actors partnerships involving private companies, public authorities and international development actors.

A banner in the community of Junin reads: “A green, solidarity and productive Intag: Buen vivir, friendship, biodiversity and economic alternatives are worth much more than copper”. Source: E. Dupuits

Scaling-up territorial alternatives: The HidroIntag project

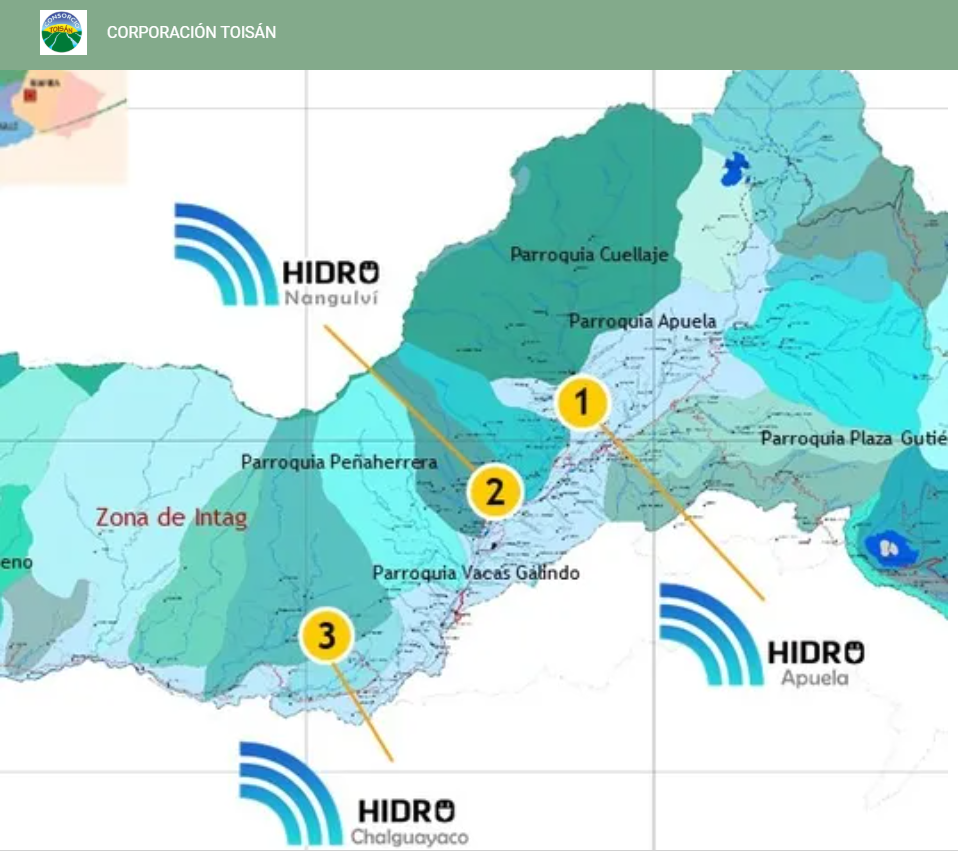

These scaling-up strategies can be seen in the case of the HidroIntag mini-hydroelectric project proposed by Consorcio Toisan in 2007. As I will discuss, the case shows the challenges, dilemmas and contradictions of building cross-scale alliances. HidroIntag aims to build two mini hydroelectric power plants in the villages of Nangulvi and Apuela, for an energy production of around 6.2 million megawatts. The energy produced would be bought by a private company producing cement, Cemento Selva Alegre Otavalo (UNACEM), and the profits would be donated to a territorial fund which would benefit nearly 68,000 families. The project was formulated in 2007 by civil society organisations of the Consorcio Toisan.

According to the President of Consorcio Toisan, “HidroIntag is based on social and solidarity economy, fair trade and local identities. It represents the communities’ hope of a territorial development from the grassroots facing mining extractivism threats”. The small-scale production of hydroelectricity will not affect the environment and will benefit directly to the communities involved. Furthermore, they consider the initiative as central for local energy sovereignty, through the inclusion of rural populations in energy production and decision-making.

Several international actors played a central role in the scaling-up of the initial proposal thanks to the existing networks of the Consorcio Toisan. The government of Cuba, through technicians from the company Cuba Solar, carried out in 2007 an assessment of the hydric potential of the basin and the first trainings. Between 2008 and 2014, the project received support from the French Syndicate of Electricity. And in 2014, the election of a new favourable administration within the municipality of Cotacachi was decisive to carry out the project.

The communities’ alliance with the municipality also proceeded from a new legislative framework enshrined in the 2008 Constitution which requires having a majority participation of the public sector in projects involving strategic resources such as water, and which promotes the conformation of public-private alliances. It is for this reason why in March 2018 the municipality of Cotacachi created a new company (HidroIntag CEM) in alliance with UNACEM and grassroots organisations of the Corporacion Toisan, to build and operate the two mini-hydroelectric plants. The partnership with UNACEM was justified by referencing the company’s social and environmental responsibility policy, and its commitment to the development of clean energy and community projects.

The communities have defended their right to full participation in the company through various mechanisms. Beyond their representation in the management structure, the communities also ensure their participation through their organisation in fifteen basin councils conformed by drinking water and irrigation committees, parish governments and social organisations of the Intag Valley. They also created a territorial fund to manage the benefits of hydroelectricity production for community development and water conservation projects.

One of the main projects which would be financed through this territorial fund is the conformation of a municipal area of conservation and sustainable development in the Intag Valley. This project could strengthen the dynamic of community water reserves acquisition by DECOIN from 1999. These water reserves are managed by the communities themselves or by the parish governments through water resources management improvement and reforestation. As of today, there are 40 community water reserves in the Intag Valley representing almost 7,562 hectares.

Beyond the conservation of water resources, the territorial fund would serve to support the productive alternatives of grassroots organisations in the region. This is the case, for example, of the Intag Ecotourism Network (REI) or the Rio Intag Coffee Growers Association (AACRI), members of DECOIN. Beyond community divisions between pro and anti-mining groups in the region, these sustainable productive projects open new economic opportunities for local residents.

Map of part of the proposed HidroIntag project. Source: Consorcio Toisan.

Emerging resistances and controversies

The HidroIntag project, and the conservation and sustainable alternatives that would be financed through the territorial fund, are facing certain resistance, especially from pro-mining groups and farmers. These tensions stem in part from the priority given to extractivism by the national government from 2007, and still in effect in the current context of economic crisis.

Beyond local resistance, the HidroIntag project is paralysed by the lack of political will of the new Cotacachi mayor elected in April 2019. This political rupture affects the project since the president of the HidroIntag company is Cotacachi’s mayor. In addition, the mayor declared a new municipal ordinance that reduces the decision-making power of the Consorcio Toisan in the company. This dependence shows a certain loss of autonomy by the communities towards public and private actors.

There is also a controversy concerning the alliance established with the private company UNACEM. Despite the fact that UNACEM considers itself to be part of the non-metallic mining sector, it nevertheless has a certain environmental impact. Indeed, the history of UNACEM is linked to that of the Lafarge cement company which owned the cement concession until 2014. According to Acción Ecológica, Lafarge is still accused today of environmental damage to the community of Perugachi for air pollution. In addition, communities question the decision to sell energy produced by HidroIntag to UNACEM and not to local users, which is the result of a law which requires the sale of energy produced through mini hydroelectric plants to private actors.

Faced with these limitations, the project is in a phase of adaptation and rescaling. The first option contemplated by the Consorcio Toisan was the sale of 50% of the company shares to the regional government of Imbabura. However, the re-elected president of the regional government of Imbabura rejected that proposal due to political interests. Another option was the sale of the municipality shares to the grouping of municipalities that is about to be legalised between several parish governments of Intag, or the development of a smaller project. A final option is the sale of the shares to UNACEM, transforming the project into a completely private initiative. If that option marks a radical change, local communities keep their confidence in the company’s social responsibility to maintain community principles. However, the credibility and confidence in the HidroIntag project especially at the level of donors, could be affected by the continuous paralysis over time.

Conclusions

This analysis revealed how the HidroIntag project evolved from its territorial and community identity when it was created, to its appropriation by private and government actors. The multi-actor partnership implied an increasing dependence of grassroots organisations on the private sector requirements of economic and financial sustainability. Furthermore, the HidroIntag project has been paralysed by political interests at the regional level that go against the territorial and anti-extractivist imaginaries initially promoted. In response, grassroots organisations seek to rescale the project to a private-community initiative, or go back to their territorial bases.

The case study of HidroIntag enlightens the broader challenges of scaling-up territorial alternatives to water extractivism. On the one hand, grassroots actors often have to adapt their initial claims based on degrowth and commoning imaginaries to fit with governments, experts and private companies’ interests in ecomodernism and sustainable development. On the other hand, grassroots actors seek to respond to their limited participation in multi-actor partnerships, and the barriers brought by regional State actors, through rescaling back the initiatives toward territories. Finally, the case study discussed reveals the constant changing meanings and imaginaries related to water commons and anti-extractivist territorial alternatives.

—

Émilie Dupuits holds a PhD in political science from the University of Geneva, Switzerland. She is now working on a postdoctoral project funded by the Swiss National Foundation (FNS) on water commons, grassroots movements and socio-technical imaginaries in Imbabura, Ecuador.

One Comment