By Lydia Karazarifi

The 10th-year anniversary of the self-organized referendum against water privatization in Thessaloniki and the annual celebration of seeds in Stagiates inspired reflections about what it means to unite different layers of water as a commons and about new democratic possibilities and forms of coexistence between people and water.

Growing up in Thessaloniki, I came across a terrain of social struggles for the defence of water as a public and common good. Memories of celebrations, assemblies, events, international encounters and knowledge exchange regarding water connected to other goods such as land created a space questing alternatives through intersected collective and individual spaces.

In one of these encounters in 2014, I remember Oscar Olivera speaking about the Bolivian Water Wars (1999/2000) bringing a bottle of water from Cochabamba to Thessaloniki, a precious gift and a symbol of solidarity as the city organized a water referendum. Water struggles emerged intensely after the ‘90s in the European context, influenced by this and other Latin American struggles for commons. Water embodied different meanings in diverse contexts, from life to democracy. Water united many communities and created bonds of alliance.

In recent years, stream of policies for the privatization of water continued to interfere with the protection of water as a commons and public good. However, the water movements remained in the social sphere to produce alternative proposals towards water justice and democracy. Some of the questions within the water movements that came to the surface were: How do we decide? How can we create something different around the protection of water? What can we learn from other social movements? What can be learned from the Greek context?

These questions have been central to my understanding of water and commons since then. After starting my PhD in political science and sociology, the focus on these questions and the seeds produced by water movements were connected to proposals for participatory democratic forms of action and collaboration and to negotiations between water as a public good and water as a commons. Some of these proposals are created in the European context through collective actions of social movements emerging at local and municipal levels.

In the meantime, particularly during the last two years extreme water-related phenomena have added new questions related to the management and coexistence with water. It became apparent that water can have a destructive force apart from its life force. Heavy rainfall and floods connected to problematic spatial design and unpreparedness for emergencies affected the region of Thessaly in September of 2023.

Here, I reflect on some water stories that suggest democratic possibilities and forms of coexistence between people and water. I focus on recent events in the Greek context aiming to unite different layers of what water as a commons can mean nowadays through problematics, encounters, moments of joy and knowledge exchange.

Thessaloniki, 17th of May, 2024

“We Continue For The Water”

The warm weather reminded the need for a higher consumption of water. Brochures on the streets of Thessaloniki announced a public event in Nea Paralia, the city’s seaside to commemorate; the 10th year anniversary of one of the most significant recent events related to water mobilizations in Greece, the self-organized referendum against water privatization in 2014.

Despite its unofficial character, the referendum was organized by the Union of EYATH (the public water management company of Thessaloniki) and local movements (Movement 136, Water Warriors), with the support of more than two thousand volunteers, lawyers and international observers. The vivid days of that time were characterized by community-building and a connection of different teams and people that some called the “water people”.

The referendum had a significant result: 98% against the privatization of water, with the participation of more than 50% of voters registered in the electoral catalogues lists. The referendum was connected to a chain of other water movements worldwide such as Latin American water struggles in Bolivia during 1999-2000, the Italian referendum of 2011 against the privatization of water services, and other influential encounters in France, Italy and Berlin.

Photo 1. The place of the 10th year anniversary of the self-organized referendum against water privatization in Thessaloniki (co-organized by the Union of the Water Company of Thessaloniki, EYATH, and the SOSte to Nero movement) with the brochure entitled “We Continue For The Water”. Source: Facebook page of Water Warriors.

Giorgos Archontopoulos, one of the speakers and president of the EAYTH Union, who participated in the referendum campaign, narrated some critical points of this citizens’ platform to defend water as a public service and common good.

Since the ‘90s, there had been pressures for privatization of water services. These were intensified after the 2008 global financial crisis, with the introduction of the stocks of EYATH and EYDAP, the state-controlled water companies of Thessaloniki and Athens, into TAYPED, the Hellenic Republic Asset Development Fund (HRADF). (The other water companies in Greece function under municipal authority).

According to Archontopoulos, the union of EATH along with other movements and public initiatives got inspired and received knowledge and experience from other referendums aiming to care for water and mobilizing the citizens to protect public services and goods. Something that became clear was that the privatization of water services could be done through direct and indirect forms; and that some indirect forms involved partnerships between public and private entities.

Based on the above, social movements in Greece were mobilized and alerted to the protection of water. The increased mobilizations of water movements led to the removal of the water stocks of EATH and EYDAP from TAYPED in 2023 by a decision of the higher court. However, as water activists mentioned, water struggles continue, and new issues are emerging.

A significant one is the reform of the Energy Regulatory Authority (RAE), an independent entity regulating energy and waste to also include the water sector in its functions and to be formed as Waste, Energy and Water Regulatory Authority (RAAEF).

This reform was voted on in the Greek Parliament in March of 2023. The water movements and the trade unions of the water services opposed it, as they considered it to be the first step of another attempt to privatize water services; after almost a decade of the referendum campaign, the movements went back to the streets. A concert with great participation took place in the central square of Aristotelous to denounce any form of water privatization. At the same time, the degradation of water services and water-related disasters connected to climate change has become another crucial issue, which raises some further questions related to water policy.

Kostas Voudouris, the second speaker of the 10-year referendum anniversary event, professor at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and member of UNESCO’s Water Centre, put emphasis on a new reform that could influence water regulations in the whole country. After the extreme storms of Daniel and Elias taking place last September in the region of Thessaly, which led to flooding, destruction of the roads, water and electricity cuts as well as uncertainty of living, the government proposed that the local municipal water authority of Thessaly (DEYA) become involved in the management of anonymous companies as independent entities that are not under the state’s control. It is not clear how this proposal is going to be implemented.

Voudouris expects that there will be pressure towards the merging of public water companies with private companies, which would be in contrast to the national law and the public interest of water as a public good. He noted that water is a cultural legacy and should be protected as such, and that investments in municipal water companies are needed but without public-private mergers.

He advocated for reforms towards a participatory model empowering a dialogic relationship between the citizens, scientists and water; a constitutional guarantee of water as a collective good; and sustainable use through small-scale water storage, water re-use and circularity.

Photo 2. The public discussion, Thessaloniki 17/05/2024. Source: Lydia Karazarifi.

Claus Kittsteiner, an international observer in the water referendum of 2014 and a member of the Berliner Wassertisch network, and Isabelle Plichon, an activist from France and elected member of the municipal committee for water management in Lyon, along lawyers, members of environmental groups and activists, took part in the conversation.

Photo 3. The public discussion. Source: Lydia Karazarifi

To sum up, the anniversary of the water referendum can show that the protection of water services is related to particular localities and people, but is also linked to networks of alliances-beyond-a-place. People with diverse perspectives have collaborated in the negotiation of what makes water a public and common good and continue to do so in times of crisis, as well as in times of hope.

Stagiates, 18th-19th of May, 2024

“After her forced migration, a woman, on the move, took some seeds of black figs from her place of birth, Izmir in Turkey, and transferred them to her new place of residence, somewhere in the south of France, where the figs started flourishing. People from other places did the same with various seeds. So, seeds and people on the move started flourishing in different places, spreading knowledge and new aromas across territories.”

This was one of the many stories shared in the workshop of storytelling about seeds and migration in the frame of the annual celebration of seeds in Stagiates.

Stagiates is a village in the Pelion Mountain, around ten kilometres from the city of Volos in Thessaly, Greece. Around 70-80 permanent inhabitants live there. This village has a long history of water commoning and water struggles to protect water as a commons.

From the 18th century, the first records of the village are connected to the importance of water. There has been a tradition of community water management and self-managementof the area’s irrigation system. A.P.O.DRASIS is a group that was created in 2009, after the first attempt of the privatization of Krya Vrisi, the water source of the village, by a bottling company in Volos, the closest city.

The village got integrated into the municipality of Volos in 2011 as part of the Kallikratis reforms, which affected the water regulations and threatened the disruption of the relations between the locals and water.

People in Stagiates resisted to the privatization and chlorination attempts of Krya Vrisi and organized collective actions towards the improvement of everyday life in the village. They created paths to the mountain of Pelion, enhancing the connections among the villages and the city, as well as library points in the paths in and close to the village, cinema nights, cultural events, educational and collective activities related to the maintenance of the water network.

Moreover, the community of Stagiates is connected to other movements working to take care of the commons in Greece and abroad. There is a continuous movement in and out of the village through these water flows.

The annual celebration of seeds, co-organized by A.P.O.DRASIS and Aigilopas, is an important meeting point for different environmental and social movements, activists and people who are interested in the exchange of traditional seeds, knowledge and experience around environmental politics –and very much connected to water.

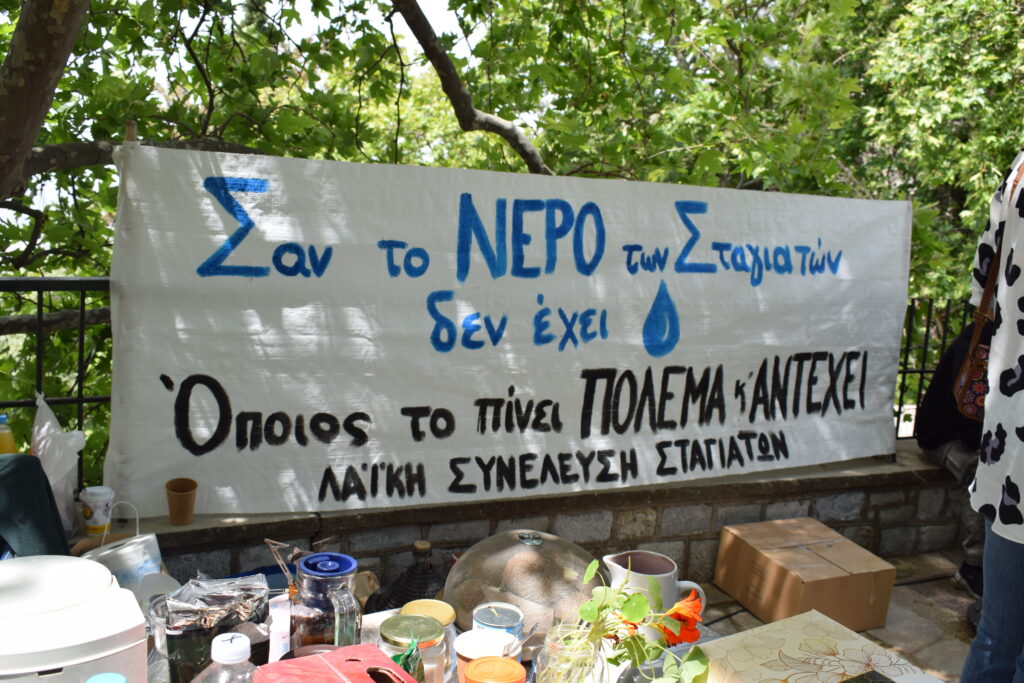

Photo 4. “Like the water of Stagiates there is none. Whoever drinks it fights and endures” Stagiates Popular Assembly. Source: Lydia Karazarifi.

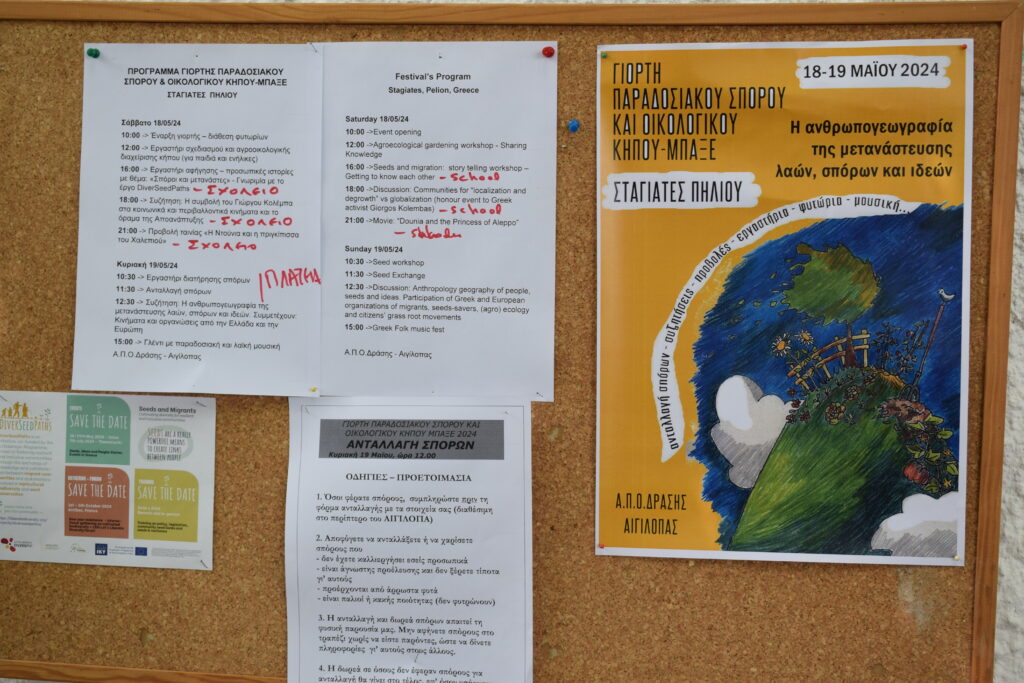

The theme of this year’s celebration was focused on commons, and was devoted to Giorgos Kolebas, who died a year ago and was an important thinker, activist and writer on the commons. The celebration included discussions and workshops on the theme “The anthropogeography of migration of people, seeds and ideas”, looking at the intersection between seeds, commons and migration, through different stories and examples shared.

A central question around these topics was how they are interrelated through the different stories and examples that can be shared.

People from France shared their stories about agroecology and possible collaborations between different territories. Other stories were about extraction from the ground, the renewable energy constructions that might harm the land, and there is interplay between oneself and the land. Activists from different places in Greece expressed their experiences concerning climate change, such as the melting of ice and the changing of the economic activities in the places they inhabit.

At the same time, I heard stories about the sharing of water from Stagiates to a refugee camp of Moza by members of the village’s community in 2016, and to the region of Pelion and Volos during and after the floods last September. Another story was about the learning of a traditional recipe to bake bread shared by Roma communities in a previous seed celebration in Stagiates.

Photo 5. Brochure of the annual celebration of seeds in Stagiates, Pelion Mountain. Title: “Anthropogeography of migration of people, seeds, ideas” and program attached. Source: Lydia Karazarifi.

Photo 6. Seeds exchange. Source: Lydia Karazarifi.

Fragments of life, possible disruptions and ideas unfolded through testimonies and stories.

“The seeds accumulate knowledge from different generations”, as noted by a farmer. The people might follow similar processes. Knowledge and culture production can be spread through the exchange of traditional seeds, the movement of people and ideas.

The discussions followed an open and participatory fashion of cultivating and exchanging stories and their sprouts. They were located in the school of the village, which works as a communal space, and in the main square. Some meters from there, the Krya Vrisi water source provides the local populations in Stagiates and the broader region with water in times of need.

In the same way that the flowing water spreads solidarity, moving seeds connect diverse communities proposing alternatives, knowledge and culture exchange, resilience and care for the community and the environment, and new stories for life-making. The celebration ended with seed exchanges, music, dancing, and eating together in the main square.

Photo 7. Glenti (meaning celebration in Greek), collective dancing in the main square of Stagiates Village. Source: Lydia Karazarifi.

Conclusions: Some Common Ground Towards The Commoning of Water

In his book Omnia sunt Omnia Sunt Communia. On the Commons and the Transformation to Postcapitalism, Massimo De Angelis states that commoning can be seen as “the life activity through which commonwealth is reproduced, extended and comes to serve as the basis for a new cycle of commons (re)production, and through which social relations among commoners – including the rules of a governance system – are constituted and reproduced” (De Angelis 2017:201). On the other hand, the collective actions of social movements are particularly essential for the protection of the commons.

Through the stories of two events –the Thessaloniki water referendum and the Stagiates community initiative, it becomes evident that water can connect different environmental and social struggles at different scales but facing similar challenges.

Commoning is being re-negotiated towards the different crises, from the economy to the climate. The role of local communities is crucial to carry on struggles that are rooted in the local environment and shaped by traditional knowledge. The dialogic relationship between the different needs can unfold possibilities towards democratic alternatives considering the environmental limits.

The different stories can cultivate hope as seeds as well as new life potentials towards care and solidarity for diverse communities.

Lydia Karazarifi is a PhD Candidate in Political Science and Sociology at Scuola Normale Superiore in Florence, Italy. She participated in water and earth movements and other initiatives on the commons. Her research focuses on water as a commons and commoning in times of crisis. Apart from her research, she is an amateur in photography and multimedia.