In Part I, we looked at how shepherds in the Pyrenees are breaking down borders and bringing back old practices of pastoralism to restore the sustainable practice of seasonal migration with their flocks. Now, let’s explore the recent history of the anarchist guerrillas who repeatedly crossed these mountains in the fight against fascism, which was also a fight against private property and for the commons.

These mountains fight back

Shepherds are not the only border crossers and mountain hikers who don’t fit within a lucrative outdoor sports demographic. Around the world, crossing borders is an act of subversion and survival, from the rough terrain of the Balkans to the watery grave of the Mediterranean to the scorching heat of the Sonoran.

It was not so long ago that the border that runs between the Pyrenees’ highest peaks, a border that also divides the Catalan and Basque countries between the modern states of Spain and France, signaled the divide between dictatorship and democracy. For many people, this was a difference between life and death. Franco, the fascist dictator, did not die until 1975, and Spain did not have a democratic constitution until the end of 1978.

Of course, the line between dictatorship and democracy is more of a membrane than a wall, as I hope to show in a forthcoming book. Both are ruling class strategies for social control, generally corresponding to different conditions and circumstances. The secret services of democratic Britain and France regularly passed on information to the secret services of Francoist Spain to help keep the plebes in line. But the plebes would not stay in line, and they exploited the membranous character of the border and the porous Pyrenees to the best of their ability.

Maquis is a French word referring to the dense bushes that grow in the wild fields or on mountainsides. A euphemism for guerrilla warfare—those who head for the hills and must make their beds in the brush—it was adopted into the Catalan language in a consequential and bloody history.

Three anarchist maquis conducting reconnaissance while crossing the Pyrenees, April 1948

Catalan revolutionaries made up an important part of the guerrilla resistance that often had to take to the hills in the fight against the Nazis during World War II. In fact, la résistance was a truly international affair, and many of the hundreds of thousands of Catalans, Basques, Castillians, and other Iberians who fled across the mountains in 1939 made up a significant part of it.

Anarchists from Catalunya had survived the repression of the Spanish Civil War, both the firing squads of the fascists and the cheka torture chambers of their erstwhile Communist allies. Once in France, they wasted no time in throwing themselves into the struggle against the Nazis and Vichy collaborators. They were the ones who liberated Toulouse, and they were in the first Allied column to enter Paris. They expected that at the end of the war, the Allies would also sweep away General Franco, but by the time the powers that would become NATO made their alliance with fascists public, the anarchists had already decided to stage the war themselves.

The contents of an anarchist guerrilla’s backpack

In a Catalan context, els maquis are the guerrillas and resistance fighters who set up bases across the border in France and organized expeditions to smuggle in radical literature, to support clandestine workers’ struggles, to sabotage infrastructure, to liberate prisoners, and to assassinate members of the Franco regime. Their struggle lasted from the early ’40s until 1963. They were an influence and an inspiration for the autonomous workers’ movement that exploded across Europe in the late ’60s, and their experience and strategies were a major reference for the guerrilla movements that grew up across Latin America in the 1950s.

However, communist organizations from Uruguay to Cuba that received direct material support from the maquis made a key change to the methodology. Whereas for the anarchists, the guerrilla struggle existed to support an autonomous workers’ struggle, meaning the organization supported the class, for the communists the guerrillas would become the nucleus of a vanguard organization meant to lead the class. Even where they were militarily successful, those who accepted this change in ethics and method simply replaced old colonial aristocracies with a settler-led Party.

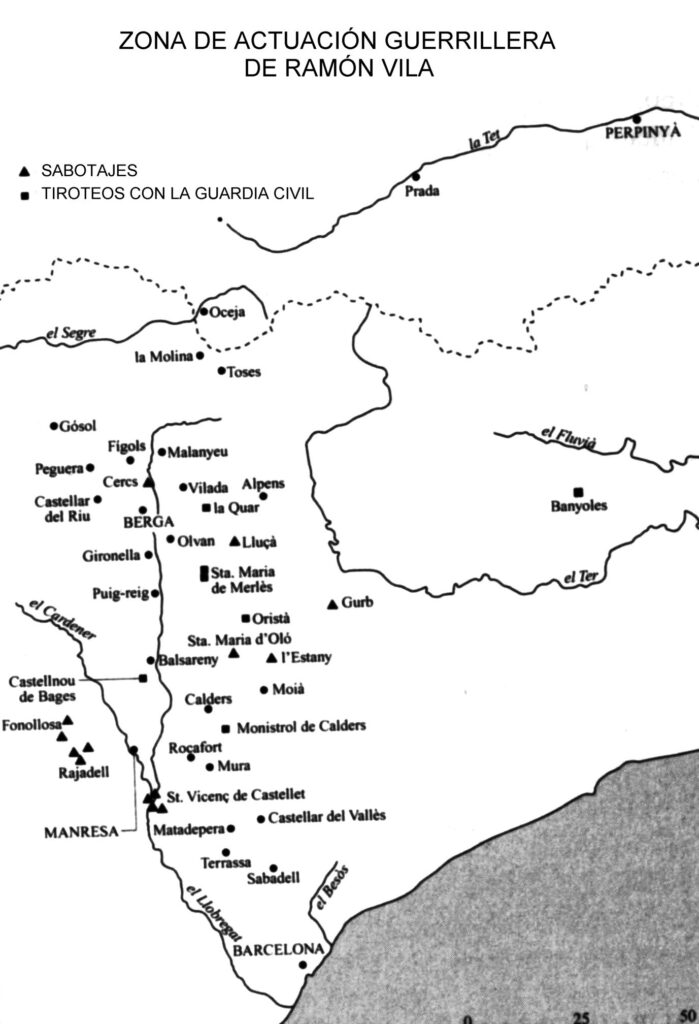

Map showing the crossing routes, as well as the sabotage actions and shoot-outs the Catalan anarchist Ramon Vila Capdevila engaged in over 20 years of clandestine crossings.

Remembering all these efforts and all these defeats, though, may well be the first step to imagining a different outcome. Professional historians treat our subversive past like archaeology, something to be dusted off and placed in a museum, putatively out of harm’s way but in truth, where it can do no harm. Our movements are learning to treat history like another commons, something that will nourish us if we take care of it. In the Pyrenees, there are still some veterans of the maquis sharing what they lived through, helping us gain perspectives for the future.

Unearthing a common history

Joan Busquets has walked this mountain path many times, though in the past it was always at night. Now he’s an old man and the police are no longer on his tail, though they certainly keep tabs on everyone who is along for this little hike, and a few have been the subject of anti-terror investigations in recent history. (As with most such transitions, the Spanish police experienced almost no change in their structure, personnel, or training as the government switched from fascism to democracy.)

A half hour trek from the old stone bridge, he points out the abandoned farmhouse and tells the story. The family who lived there were sympathizers. Often around the fourth night hiking from their bases across the border—always at night, never under a full moon—the maquis would stay here. If the weather permitted they would sleep around back, where there are some pine trees growing now. The family would let them know if Guardia Civil were coming up the path, giving them enough warning to hide in the woods. Otherwise they would rest up and plan the next action. It might entail blowing up a power line to frustrate Franco’s development plans, or beating up a fascist boss on the factory floor in support of the workers who continued to organize clandestine unions at one of the peri-urban industrial colonies. Other times the guerrilla affinity group would head into Barcelona to coordinate with the clandestine Defense Committee or attack a police station.

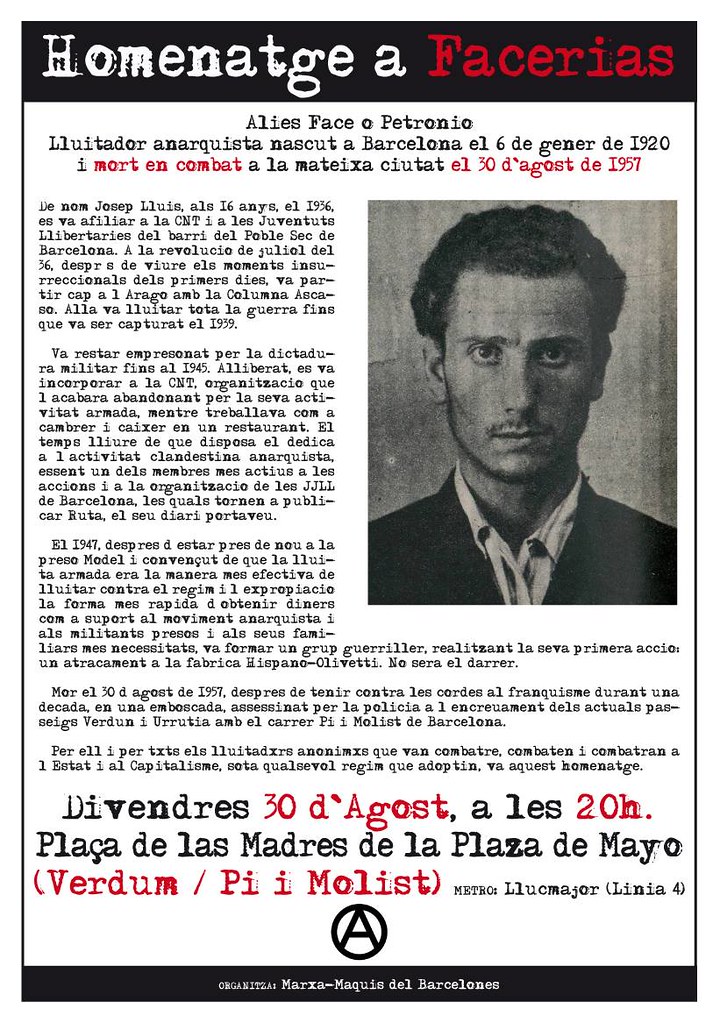

Poster for a 2013 event remembering the life and struggle of Josep Lluís Facerias, held on the square in Barcelona where he was gunned down by police in 1957.

In 1949, Joan was arrested in Barcelona and given the death penalty. His sentence was commuted to long-term imprisonment due to his young age, but the other members of his group were either killed during arrest or executed by firing squad. Resistance continued inside prison walls. But the movement had a much harder time surviving the Transition to democracy (referred to as the Transaction by its critics).

In the 1970s, as one of the largest wildcat strike movements in the world shook the foundations of power, the Left sat down at the table with the fascists and shook hands over a new constitution that left the most fundamental structures of power unchanged. Within a couple years they would win elections and hold onto power for well over a decade. The memory of the maquis and the revolutionary, anticapitalist movement at the heart of the resistance was no longer convenient. It was placed in a museum, mentions of its most radical elements excised, and society was instructed to look ahead to a future that everyone by now has found wanting.

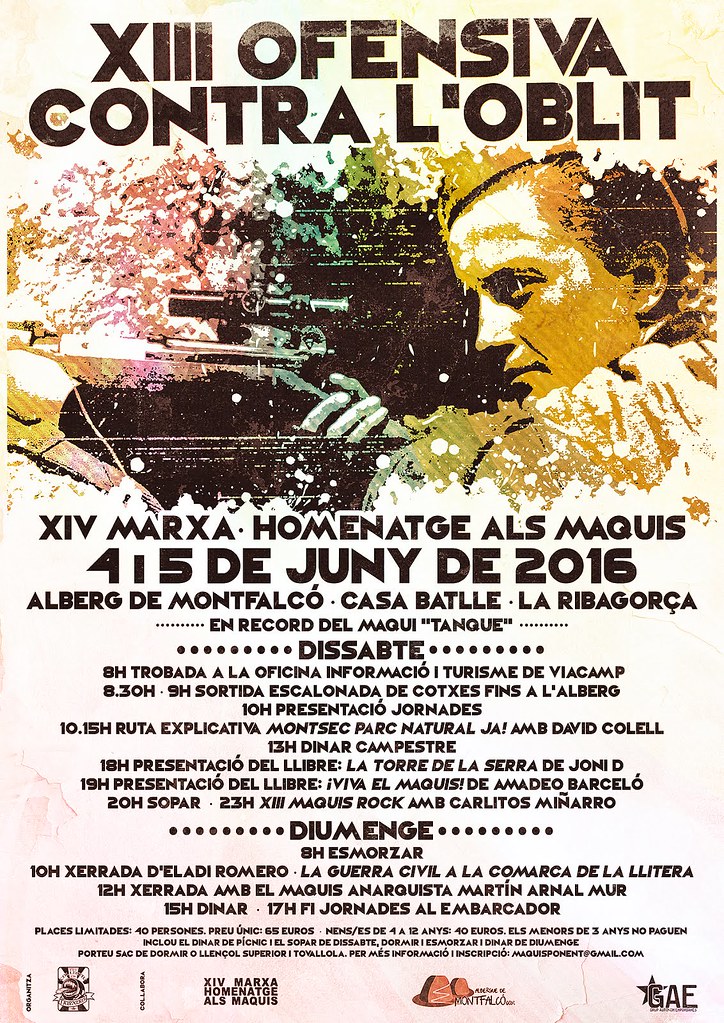

Poster for a 2016 hike and weekend of events commemorating the maquis.

One of the most important activities of the Iberian anarchist movement in the current period has been to treat history as a commons, as a living thing that gives us sustenance and that we in turn must refertilize, share, and locate ourselves within. Numerous groups have turned to our elders, interviewing them, publishing their memoirs, making sure they are taken care of and can find a place within this movement as it grows again. Sometimes that means following in their footsteps literally, as we did on that walk with Joan, rooting history within the terrain that gave it birth in a way that books never can, a way that is diametrically opposed to the disembodied, acquisitive, alienated, and artifact-focused gaze of official history.

This is memòria històrica, history as commoning, from below and within.

This direct transmission and collectivization of memory has accompanied another process, reaching even further back. Recent work has transformed our relationship with this land, taking its inspiration in equal parts from two sources. One source are the local historians reminiscent of—but much more chthonic and socially engaged than—E.P. Thompson, author of the aforementioned Whigs and Hunters. The other source are the residues of folk wisdom that many families can still access to trace themselves back to their ancestral villages, flung in a wide arc across the whole peninsula.

This latent memory, in most people, bears nothing of the subversive, and is nothing to be romanticized. Potentially, life in the villages can be as soul-destroying as life in a US suburb, even if the houses are much better made. But combined with the recently flourishing historiography of the commons, such memory can facilitate people developing an embodied understanding of primitive accumulation and the war on the commons.

E.P.’s account of the “Black Act” and how a modernizing English state executed peasants simply for gathering firewood from the old commons can demolish our sense of the foundations of modernity, but even if you live in the British isles or your distant family members emigrated from there, reading that history is unlikely to change who you engage with the land and engage with resistance in the present moment.

In Catalunya and other parts of the Iberian peninsula, however, recent efforts to pierce capitalism’s erasure of the past and uncover what proves to be an abundant history of peasant rebellions, battles for the commons, and early luddites, have gone hand in hand with anticapitalist efforts to win the commons back. That’s because instead of just history, we are dealing with historical memory, which in its best form is embodied, rooted, and territorialized. There is a major qualitative difference, after all, between reading something in a book, and having an adopted grandparent, a revolutionary elder, entrust you with a memory and ask you to pass it on.

What is remembered can be resurrected.

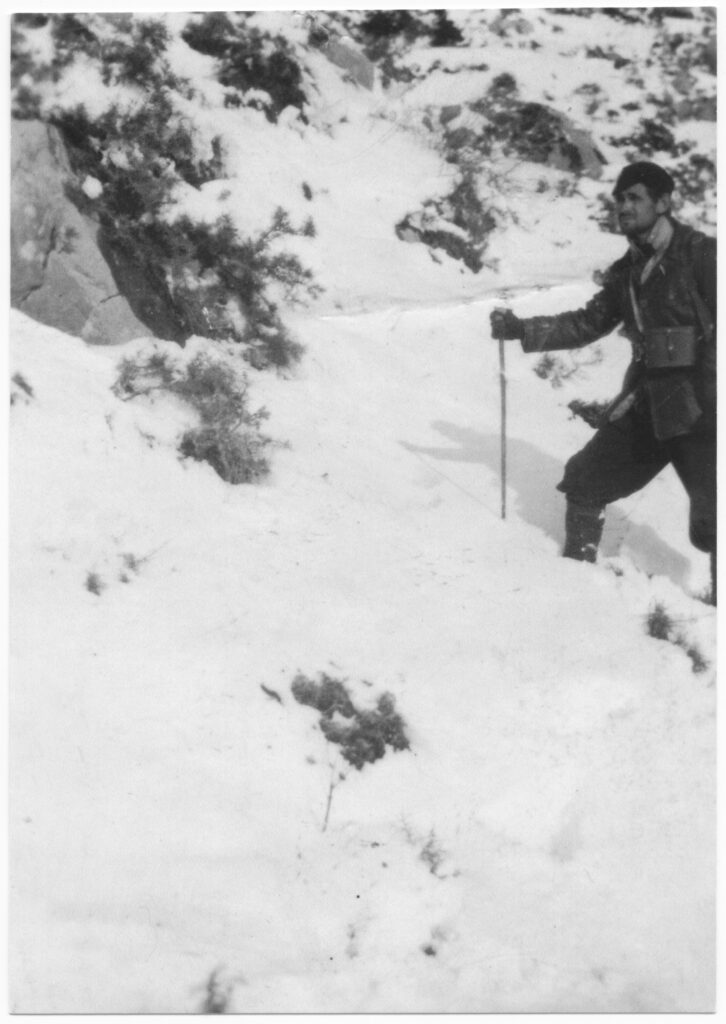

Photo of Quico Sabaté crossing the mountains in the snow, from the archive of his daughter Alba

The presence of the past also appeared in the interview I did with Edu Balsells, the shepherd who is resurrecting old practices of commoning and migration. Edu is an activist for sure but at the end of the day he is someone who is trying to make a living. And yet he casually drops references to peasant insurgents and anarchist maquis in between comments about different sheep breeds and the onerous nonsense of government regulations. Just as he seeks to share the mountains with other shepherds, other flocks, farmers, forests, other species, he shares the mountains with the ghosts of resistance past.

Likewise, Catalan feminists today are recovering their memory of the trementinaires, the healers and witches who traversed the mountains collecting medicinal herbs, a practice dependent on access to the commons and in turn necessary to a practice of healthcare that was held in common rather than individualized and monetized. And many of these radicals are part of the large and growing number of precarious youth who turn their backs on the competitive world of individual careers (a world that long since turned its back on them), and instead occupy abandoned farmhouses and mountaintop villages, reinvigorating a living commons in a space that capitalism had let fall through the cracks. In explicit reference to their anarchist elders, they support one another through mutual aid networks across a multitude of projects.

In summary, industrial agriculture led to the abandonment of these mountain villages that were once an anarchist stronghold and are now being squatted and reinvigorated as sites of resistance. Industrial agriculture is also a major source of greenhouse gas emissions. In Catalunya in particular, it’s a motor of erosion and desertification. And in a mountainous terrain like this one that puts an upward limit on the gigantic machinery employed, capitalism often cannot find a way to put agricultural land to use.

Edu Balsells might seem like a throwback in our modern media landscape, but in actuality he and shepherds like him are deploying some of the most versatile and effective solutions to the ecological crisis. Those who are taking up agricultural commoning in the mountains are also developing one of the best solutions available in the present circumstances. They are growing food in a way that increases biodiversity, repairs erosion, refertilizes soil, draws carbon out of the atmosphere, and increases food security and food autonomy. These new commons have the capability of becoming robust, far more immune to supply chain snarls and capitalist disasters than supermarkets. And the ethos, the very logic of sharing that motivates them, makes the new commons the perfect antidote to the engineered scarcity of capitalism. Given how many movements in the Global South are centered around the defense of surviving commons, this focus also creates a point of affinity necessary for developing truly countercolonial struggles and solidarity in the countries that are the foremost architects of global apartheid.

Likewise, Joan Busquets and other survivors of the armed struggle are not the relics of an irrelevant cause. Feminists reviving the herbal knowledge of witches are not hobbyists. They remind us that somewhere in our past, we missed a very important turn, and we are currently stuck on a trajectory that will make survival impossible. We are driving full speed towards a cliff because semantically we have been convinced that progress means never acknowledging that our society has committed some fundamental mistakes.

The ability to feed ourselves, the intentional turn towards a solidaristic approach to healthcare, the need to act like members of a community and to heal the land, to heal those relationships, the memory that food and health and land and relations didn’t just disappear, they were stolen from us as deliberate acts of social war, the determination to locate ourselves within a centuries-long war and learn how to fight back – these may be the most important elements of our future. If we are to have a future.

Franco the environmentalist

Hydroelectric megaproject built under the Franco regime on the river Ter, Catalunya (credit: Xavi Larrosa)

The mainstream conversation around the ecological crisis is reduced almost entirely to climate change, with a technocratic focus on greenhouse gas emissions, emissions reductions, and some industrial form of carbon capture. The intelligence and effectiveness of the technocrats can be amply summed up by the litany of missed climate goals, all the spent resources and institutional efforts that still haven’t decrease greenhouse gas emissions, or by depressing factoids like: carbon capture has been used primarily to increase the output of oil and gas wells.

This conversation has no room for the commons, because it is too busy promoting huge new projects like giant wind parks or modernized airlines with highly paid climate accountants, smugly promising that their pollution-heavy industry is actually carbon neutral. The official conversation creates a terrain that is much less like the mountains with their hidden paths and complex gardens, and more like the monocrop plantation or the factory floor, terrains built for surveillance, for massing people together while also atomizing them. In a conversation designed by powerful institutions and invested so heavily in by major corporations, there is little for the rest of us to do other than what we’re told.

The great big solution to climate change is… acceptance. Accepting a change designed to keep power and profits in the hands of the very institutions and companies most responsible for the crisis. There is a parallel here: one of those rhymes of history we should know to pay attention to. Acceptance is also what was demanded of the Spanish population in the ‘70s, after Franco died, the Socialists shook hands with the fascists, and democracy was installed. The fundamental power dynamics in society had barely changed, as other tools were introduced to accomplish the same goals.

So it is with green energy. As I argue in The Solutions Are Already Here, “Ahead of Another Summer of Climate Disasters,” and other writings, the goals of the mainstream climate framework are not to heal the planet, but to allow the same players to hold onto their power and profits, while allowing some new players at the table, and introducing some new tools to help get the job done.

Many of these supposedly new tools, however, are actually not so new. Interestingly enough, the mountainous terrain we have been walking through has been a major site of green energy production for over half a century. More interesting still, it was Franco the fascist dictator who had most of it installed.

The giant hydroelectric dams that have engulfed valleys throughout the Pyrenees, submerging dozens of villages and cutting off hundreds more, are nothing if not a war against the mountains themselves. Many theorists have commented on the preference of dictators for infrastructural megaprojects. Such projects give them a chance to focus the power of the State, to prepare emergency response powers within the authoritarian logic of disaster management and to either flatten a rebellious terrain or make it uninhabitable. In the context of the Global South, Vandana Shiva writes about how megaprojects like dams show up again and again as a weapon of continuing (neo)colonialism.

The State impulse towards social control often manifests as a war on nature, particularly in areas with a geography that make homogenization, massification, and surveillance difficult. In Dixie Be Damned, Neal Shirley and Saralee Stafford (2015) effectively draw out this aspect of the conflict between the plantation class and the enslaved workers or sharecroppers in swamp regions of the US South.

Analyzing industrial wind farms in Oaxaca, Mexico, Alexander Dunlap and Martín Correa Arce (2021) have brought us up to date, also using a counterinsurgency framework, to show how the major worldwide push for so-called green energy plays directly into ongoing repressive campaigns and continuing colonization and re-engineering of the territory for the purposes of social control.

While the recent spree of wind turbine construction across Catalunya does not come with the paramilitary violence needed to carry out the same construction in Oaxaca—in Oaxaca there are still Indigenous communities defending the commons, whereas in most of Europe the countryside has already been depopulated—these wind farms are nonetheless a continuation of the legacy of Franco’s hydroelectric dams. And those in turn were a continuation of the massive deforestation of the Pyrenees in the 19th century, to build the railroads, launch the steel industry, and at the same time impoverish the commons that gave sustenance to the rural peasantry who made up the backbone of so many social rebellions in those years.

Under capitalism, there is startlingly little difference between such vastly different sources of energy. And today’s wind farms and other energy infrastructures, though they seem to lack the explicit violence of their forebears, have already been linked to expropriations and other conflicts that affect the growing wave of people resurrecting the commons. And more than that, they constitute a chess piece played with perspicacity, holding down a position so the enemy—that’s us—cannot take it.

Green energy remonetizes many rural spaces that a cumbersome industrial agriculture had had to abandon, and it architecturally occupies those spaces in a way that prevents us from resuscitating the commons, accessing land, and cultivating food autonomy, a healthy relationship in which we heal the planet and ourselves without any need for State or Capital.

To reclaim those commons, we would have to sabotage the swelling green infrastructure that constitutes the great hope of mainstream environmentalists, and that too is intentional.

Peter Gelderloos is an independent researcher, writer, and social movement participant. He is the author of The Solutions are Already Here: Strategies for Ecological Revolution from Below, How Nonviolence Protects the State, Anarchy Works, Worshiping Power: An Anarchist View of Early State Formation, and other titles. His works have been translated into fifteen languages. You can follow his work on Surviving Leviathan.