By Alexander Dunlap and Carlos Tornel

Summarizing a recent conversation in Globalizations, this article seeks to provoke a dialogue on environmental and energy justice, political affinity, statism, everyday warfare and the concept of activism.

The planet continues to be engulfed by socioecological catastrophe. With no shortage of warnings: not only from within elite and policy circles, such as the Limits to Growth Report (1972), but also from the centuries of nearly endless actions of people fighting to defend their habitats, from the Bogs of England to the Lacandon Jungle. This present, and predicted, situation remains pressing. Meanwhile, institutional and academic responses appear inadequate, where the word ‘critical’ downplays a necessary hostility against the existing methods of organization, planning and development imposed on the world by force, deception and allurement strategies. While “critical” engages and negotiates—empowering systems and discourses—hostility rejects, fights and abolishes.

Discussing these issues in a lengthy exchange in Globalizations, we have drawn to the fore some harsh realities worth highlighting. From different perspectives, and positionalities, we have located five general points within this dialogue challenging the existing hegemonic situation in academia. Starting from a discussion of environmental/energy justice, the purpose, then, is to highlight these issues related to political affinity, statism, everyday warfare and the concept of activism itself. While we only speak briefly to each of these issues, our hope is that this piece is read as a provocation for scholars to address and engage with discussions concerning justice.

Environmental and Energy Justice

We embrace environmental and, to a degree, energy justice. Carlos, as well as other political ecologists such as Tristan Partridge, have revealed the policy-centric and technocratic framing of most energy justice scholarship, and have shown how it has explicitly positioned itself as ‘anti-activist’ in many instances. While this is slowly being reversed as we write, the concept of ‘justice’ still raises concern.

As a liberal/modernist concept, justice is rather limited, more so once we realize there are many conceptions of justice. This has resulted in critical, indigenous and decolonial forms of environmental justice. Environmental justice (EJ) studies’ emphasis on recognition, procedural and distributive justice, which includes capabilities to engage in the latter institutional processes, remains wedded to a teleological form of modernist progress, a cartesian society/nature dualism and a narrowly defined Western universalism.

While distribution concerns remain a useful approach, it embeds within it a reductive and pacifying effect. Focusing on fairly and evenly distributing participation within development projects, as well as the socioecological ‘costs’ and ‘benefits’, risks assuming modernist development and tends towards excluding post-development practices that want to reject modernism, statism and capitalism—even if this is not the intention of EJ authors. This is a point already recognized by decolonial EJ studies. By calling everything an EJ struggle (as the otherwise amazing EJ Atlas map also tends to do), scholars risk reducing all conflicts to a matter of distribution, leaving the desire for modernist assimilation unquestioned.

This privileges civil society groups and movement leaders that promote fair and more equitable development, as opposed to wider transformations and ‘societies-in-movements’. This is an ever-present tension in environmental conflicts, which exists between a desire to survive and living comfortably under states and capitalism versus post-development alternatives rooted within convivial and vernacular trajectories. NGOs funds, mainstream politics and academic subjectivities behind mainstream environmental and energy justice tend to ignore autonomous, insurrectionary and self-determining tensions (rejecting modernism) in environmental conflicts. While critical, Indigenous and decolonial environmental justice respond to some of these issues, the question emerges: why integrate autonomous, anarchists and self-determining tendencies into a singular academic framework? While it is possible to call everything a distribution conflict, this underwrites political tensions and possibilities that reject statism, modernism and capitalism leaving the culprits of socioecological catastrophe mildly challenged.

Political affinity, not identity politics

Essentializing identities within environmental conflicts shows how people can be mislabeled and manipulated. People are unique, have differential experiences related to class, culture, ethnicity, (non)gender, abilities and politics. Not all people from the ‘Global South’ or Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) are anti-capitalist, let alone anti-state. Environmental/energy conflicts, considered broadly, reveal a multiplicity of political positions transcending identity—there are capitalist, authoritarian and anti-feminist BIPOC people. Tokenizing identity through modernist/developmental state programs based on ethnicity or (non)gender is ill advised and counterproductive for shaping liberatory ecologies and producing effective challenges to actually existing capitalism. Political affinity and vision can reveal more than identity, even if the two are not mutually exclusive. An individual’s politics can reveal the real intentions of people and not just using identity as a political leveler to speak on behalf of entire demographics. Identity categories, while empowering, also serve to divide, conquer and manage people within political systems.

This is not a criticism of identity mobilizations but of how state bureaucracies and procedures (i.e., community consultations such as Free Prior and Informed Consent schemes and other social-environmental impact assessments), academics and politicians tend to tokenize people’s identities, divide them from other issues and reduce these struggles to assimilationist politics. The Pluriverse aims for (relative) unity through diversity, which implies rooting anti-capitalism and anti-statism into a pluriversal struggle. Pluriversal openings will have to come into dialogue with one another, placing political affinity – based on what people know and don’t want (i.e. statism/colonialism/capitalism) – whilst recognizing differences between race, gender and identity at the center. Rooting in political affinity offers the possibility of confronting the multiple forms of (non)gender, class, ethnic and nonhuman exploitation and extraction to build alliances, complicity and alternatives to development from pluriversal openings.

See more from Indigenous Action Media (IAM). Source: IAM

Statism is colonialism

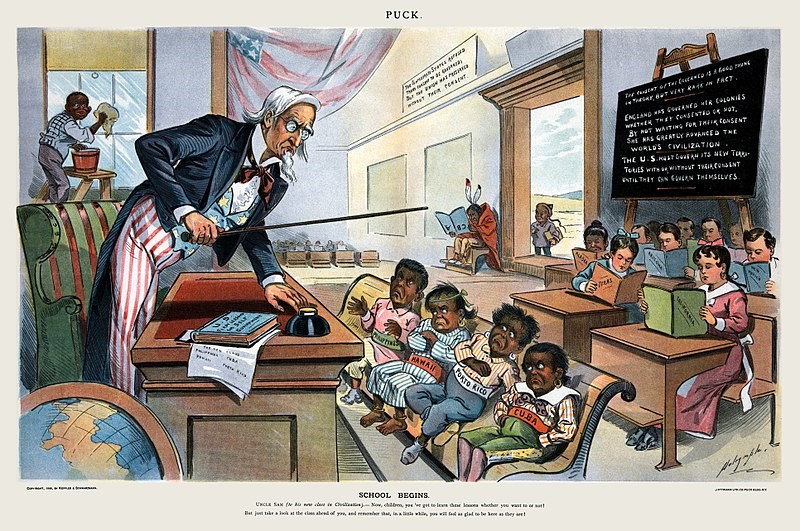

The university and NGO complex has largely captured decolonial discourse. Decolonization has slowly become a synonym for reformism—decolonizing the state, international relations, artificial intelligence, diets and so on, separating it from anticapitalism, and from abolishing the state and (ethnic) hierarchies. The relationships, habits and trajectory of modernist development remain preserved, not questioning the exterminating, degrading and carceral processes states spread to everyone—humans and non-humans. The decolonization era, for example, is known for Marxist-Leninist armed formations and, later, ‘post-colonial’ governments separating the political from the economic, embracing bureaucracy, centralized control and Eurocentric dualisms. This, of course, comes after colonial oppression and philanthropic organizations introducing and organizing educational systems.

Colonialism—discrimination, control and extraction (in so many words)—is embedded within statism and state formation, producing and affirming class, gender and ethnic hierarchies to advance the political economy of extractivism. Internal colonialism played a central role in the configuration of modern rule and liberal governmentality. Classical colonial powers—Spain, England, Portugal, etc.—could not organize colonial ventures and takeovers without first organizing this power internally by exterminating dissidents, disciplining people and environments to organize mines, factories and militaries to establish a structure of political economy. Colonialism would export this model with similar and increasing ruthlessness overseas to organize a structure of conquest and extractivism: the state. Recognizing state formation as colonialism, and continued statism as (neo)colonialism, can reinvigorate productive conversations about the existing infrastructures, organizational patterns, discourses and extractivism that seeks to divide, conquer and integrate everyone into a global extractivist economy. This recognition also creates the possibility for far reaching political affinities across classes, ethnicities and (non)genders to begin composting the colony/state that organizes and facilitates the structures of generalized and variegated intensities of exploitation and extraction.

“School Begins” (Puck Magazine 1-25-1899). Source: Wikimedia Commons

This is (low & high intensity) war

Recognizing that statism is colonialism also brings up the fact that statism is warfare, internally (e.g. state formation) and externally (colonialism), which continues into the present (neo)colonial development. Land centered peoples in the diverse territory homogenized as ‘Europe’ have long regarded the state as an instrument of war, subjugation and colonialism. By labeling “colonial warfare as ‘unconventional’ or a ‘small wars’ affair”, Mark Neocleous reminds us, “dismiss[es] what has in fact been by far the most common form of warfare in the modern world.” Imposing and convincing people of civilization, Empire and state has always been and continues to operate along the logic of warfare—which is not just tanks, soldiers and riot police, but psychological, technological and civil military approaches. The Zapatistas have called this a ‘Fourth World War,’ to animate how capitalism and statism operate as structures of permanent (and renewing) conquest through institutions and political economy. Addressing how, for example, low-carbon infrastructure is deployed, must consider the doctrine of counterinsurgency warfare, designed to defeat rebellion and maintain a statist model, along with how modernist infrastructures remain enduring continuations of statism and colonialism that articulate conventional and low-intensity social war(s) to maintain the existing state system and global extractivist economy.

Activism?

This raises the question of how researchers relate to the state and capitalist ‘development.’ All researchers have positionalities, ideological preferences and therefore perform all kinds of ‘activism(s).’ Capitalist, statist and modernist research activism conceals its ‘activism’ with implicit claims of objectivity or by branding othered knowledges/praxes as “activists.” Activism, then, emerges as a shorthand for slander, political disagreement or a miscommunication in demonstrating the way students or staff can improve narrative description, methodological write-ups, research questions and, overall, the presentation of fieldwork material.

While understandably a useful term to indicate politically motivated activities, activism is often applied narrowly and ambiguously, as it symbolizes only a limited (and domesticated) forms of political engagement (e.g. petitions, mass demonstrations, canvassing and banner drops). The relationships associated with activism, anarchists have identified, can objectify struggles, proliferate categorizations, separate people through (self-important) informal hierarchies and undermine multifaceted struggles that transcends the political norms and relationships established by self-defined ‘activists.’ This narrow definition creates a separation from the existing realities, which has an isolating and cadging effect: either embraced to fashion as an ‘activist’ commodity or having it thrusted upon you to degrade or discredit one’s work. Political conflict remains inseparable from life itself. Activism, as a term, is a discursive social control strategy that reflects liberal conceptions that maintains the existent global extractivist systems.

For militant reconfigurations

The appeal to work with ‘middle-road’ reformism, ignoring insurrectionary political tensions and struggles within the institutional realm of liberalism/modernity (which is rapidly narrowing) persists. Challenging (extreme) divisions of labor remains central. Academics, for example, are positioned as the intelligentsia, viewing people and struggles from the biopolitical vision of the academy. We advocate immersing ourselves in our habits, our politics and common struggles—moving from the desk and participant observation to becoming research accomplices. This entails dissolving the ‘home-field’ dichotomy, recognizing how researchers, themselves, are also in the metaphorical Petri dish of these political and ecological struggles—even if they can leave in most instances. Instead of relying on liberal/modern teleologically informed and dualist-framings that reproduce a coloniality of justice(s), we need to reject them. These struggles are everywhere in a global ecosystem, connected through urban centers, financial networks and extractive supply-webs. We imagine more from not only environmental and energy justice, but academia as a whole, critically reflecting on these insights in their work but also daily-lives. This means remembering nothing is separate—we all have a stake in these political struggles even when we think we don’t.

—

Alexander Dunlap is a Docent research fellow at the University of Helsinki, Finland. He has published three books: Renewing Destruction: Wind Energy Development, Conflict and Resistance in an American Context (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), the co-authored, The Violent Technologies of Extraction (Palgrave, 2020) and the co-edited volume: Enforcing Ecocide: Power, Policing & Planetary Militarization (Palgrave, 2022). Twitter: @DrX_ADunlap

Carlos Tornel is a PhD researcher at Durham University. He is the editor of the book: Alternativas para limitar el calentamiento global en 1.5°C. Más allá de la economía verde (Heinrich Böll, 2019) and co-author of Minerales críticos para la transición energética. Conflictos y alternativas hacia una transformación socioecológica (Heinrich Böll, 2022). Several of his book and articles can be found here.

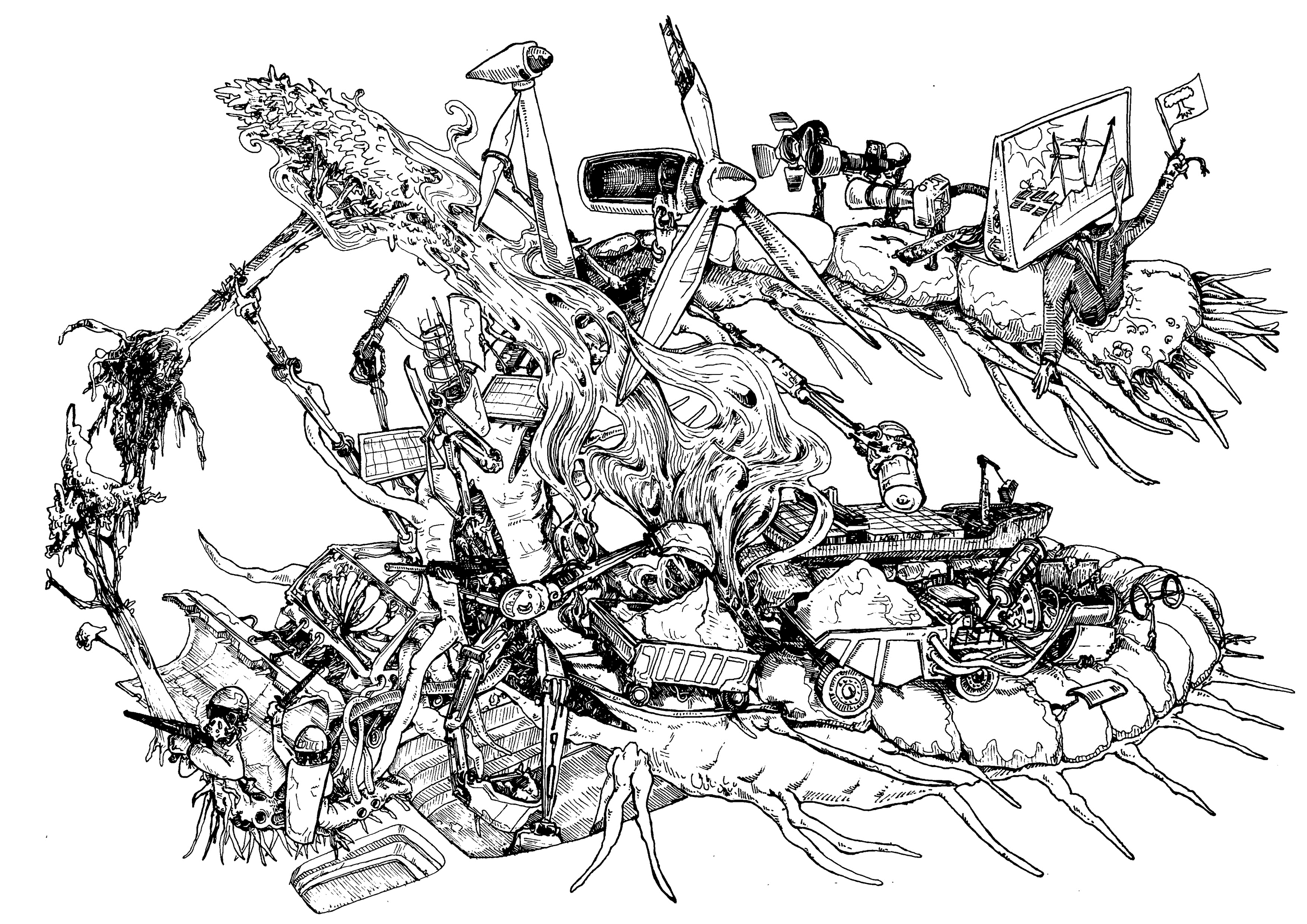

Cover image: Depiction of the ‘World eater’ consuming the people and planet. Credit: Merty Dunes.