By Japhy Wilson

Have state and capital succeeded yet again in their joint campaign against the stubborn flourishing of universal humanity? Perhaps. But the Peruvian people have awoken, and any such victory can only be temporary and contingent.

Spontaneous uprisings against grotesque injustices are frequently filled with violence and rage and desperation. But sometimes they are transfigured by moments of sudden beauty, in which universal humanity manifests itself, not as a utopian ideal, but as a vibrant truth.

A moment of this kind has just occurred in Peru. But its fleeting and effervescent character has led it to be lost amidst the tragedies and brutalities that have dominated most reports on the crisis currently gripping the country. We should pause to bear witness to this moment, just as we rush outside at night to see a rare comet streaking across our shared sky.

Betrayal

Ever since Spanish conquistadors demanded a vast gift of gold to spare the life of an Incan emperor, before murdering him on its delivery, Peru has constituted an extreme case of the violence and venality of extractive capitalism. To this day, the country remains dominated by a predominantly white elite based in the coastal capital of Lima, and the transnational corporations that control the mineral and hydrocarbon industries that sustain the economy.

The Indigenous inhabitants of the highland and jungle regions of Peru have been historically excluded from the wealth generated by these extractive industries, the majority of which are located in their territories. Their exclusion has been combined with a deeply entrenched legacy of exploitation, repression and racist denigration emanating from the capital.

Pedro Castillo, a primary school teacher with Indigenous ancestry from the impoverished highlands, was elected president of Peru in 2021, promising to address these historical injustices. It was the first time anyone with his background had come to power, and his election generated immense hope among the marginalized sectors he symbolised and claimed to represent.

But the right-wing congress refused to let Castillo govern. He was subjected to repeated impeachment attempts from the outset, which came to focus on corruption cases in which he almost certainly was indeed involved. On the 7th of December, facing a further impeachment vote, Castillo made a clumsy attempt to dissolve congress and rule by decree. The military refused to support him, and congress swiftly voted to remove him from office.

Castillo was automatically replaced by his vice-president Dina Boluarte, who had promised to immediately resign if Castillo was forced from power, which would have triggered a general election. Instead, Boluarte allied herself with the army and the most conservative elements of congress and announced that she and the congress would remain in power.

Uprising

Boluarte’s betrayal was perceived by the Indigenous inhabitants of the highlands as the culminating insult of an unacknowledged coup through which the Lima elite had disposed of the only political representative they had ever had. Furious crowds immediately took to the streets. Boluarte’s regime responded with unprecedented repression, including the massacre of 10 unarmed protesters by the army in Ayacucho on the 15th of December 2022, and the further slaughter of 17 demonstrators by the police in Juliaca on the 9th of January 2023.

The Juliaca massacre may have been a desperate attempt by an illegitimate regime to stifle an uprising that was rapidly spiralling out of control. But instead, it catalysed an unprecedented popular movement that decided to march on Lima and force Boluarte to resign.

The “Seizure of Lima” was set for the 19th of January. Throughout the country, community assemblies and regional social movements resolved to pool their funds to send representatives to Lima, and to organize strikes and blockades to put economic pressure on the regime.

In the days leading up to the 19th, provincial cities were filled with emotional scenes in which thousands of people turned out to wave off convoys of buses departing for the capital. The caravans were met with further spontaneous support along the way, in the form of gifts of food and water from the communities through which they passed.

And while the Lima elite looked on in horror, most of the population of the capital welcomed the protesters with open arms. The students of San Marcos, the oldest university in the Americas, occupied the campus and turned it into a huge dormitory, which was quickly inundated with further supplies donated by the everyday inhabitants of the city.

Labour unions, student organizations, and environmental movements joined the struggle. Artists and musicians performed for the protesters being hosted at San Marcos. Medical students formed brigades to tend to the injuries that everyone knew would come. And by the 18th, over 100 roads were blocked across the country in support of the Seizure of Lima.

As journalist Ybrahim Luna noted, despite the tragic circumstances that had motivated the movement, it possessed “a certain joy,” resulting from the collective experience of a “total identification with a cause, as when… the people bade farewell to those who filled the buses departing for the great city of Lima, amidst applause, and finally feeling part of something.”

This sense of insurgent passion was communicated by many of those directly involved in the struggle, such as a student who travelled from the highland city of Cusco, and who posted the following Facebook message to her family, after she had secretly departed for the capital:

“Mother, sorry for so much rebellion. Today we arrived safely in Lima. All along the way we heard [the chant] ‘The people, united, will never be defeated,’ while [the people] gave us water, tuna and biscuits. Many parents… wept on our departure.”

This is the humble and fragile essence of what the political theorist Susan Buck-Morss calls “universal humanity.” It is embodied in those moments when people stretched to breaking point by historical systems of injustice suddenly and miraculously overcome their racial, cultural, and regional differences and collectively express their common desire for equality, abundance and freedom. Not as a vague utopian dream, but as a visceral lived reality.

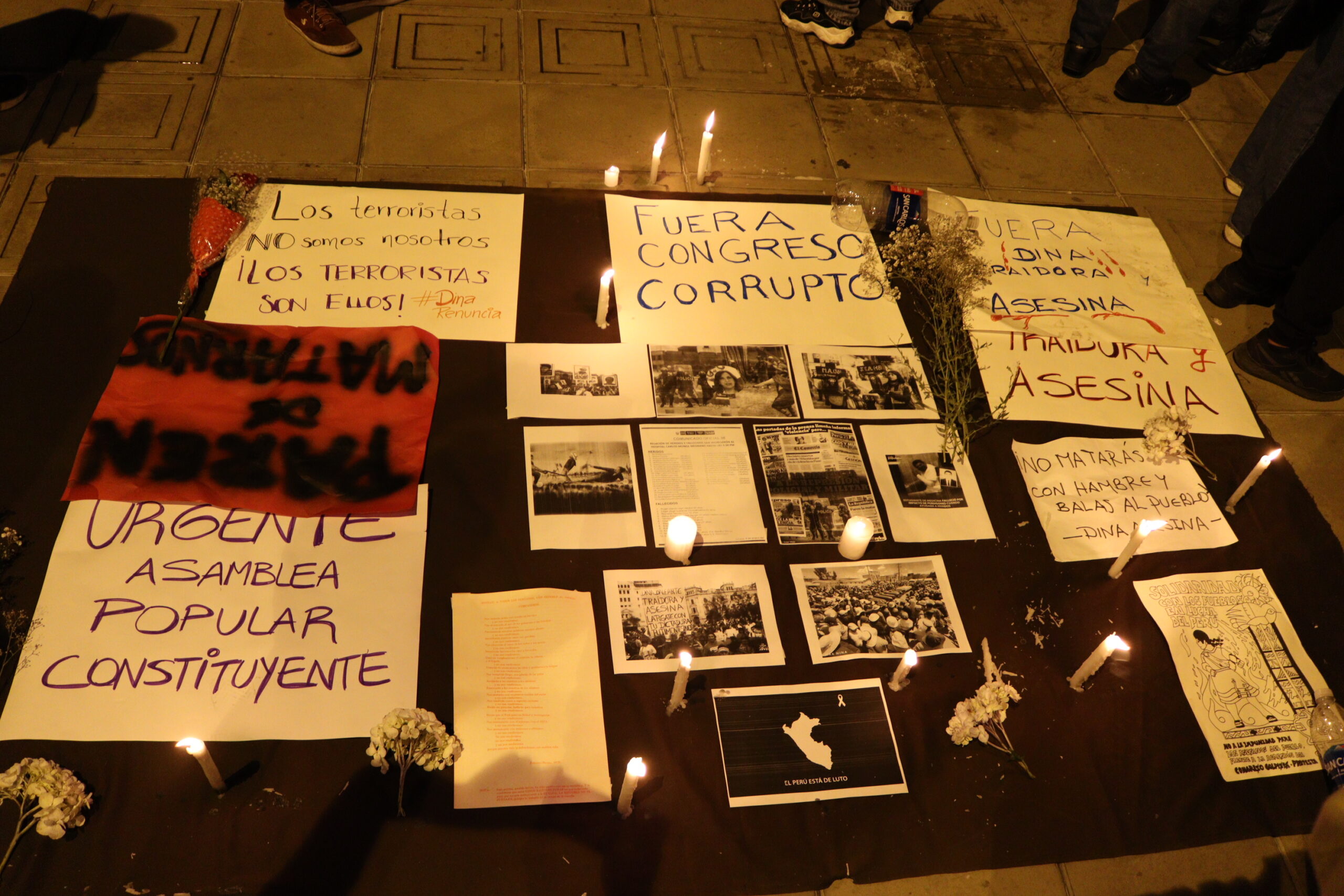

Demonstration against the Boluarte government in Lima, 10 January 2023. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Repression

The capitalist state is terrified of such expressions of universal humanity, which expose its structures of domination and pose a grave threat to its survival. It therefore seeks to crush them at any cost. As the philosopher Alain Badiou has noted, such struggles demonstrate that “over and above their vital interests, human animals are capable of bringing into being justice, equality and universality… It is perfectly clear that a high proportion of political oppression consists in the unremitting negation of this capacity.”

In my new book, Extractivism and Universality: Inside an Uprising in the Amazon, I report on a manifestation of universal humanity in the Ecuadorian Amazon, in which Black, mestizo and Indigenous oil workers united against the combined forces of a multinational corporation and a militarized state. The uprising achieved a remarkable victory. But it was eventually defeated by state and capital through a complex combination of repression and division.

The state has confronted the Peruvian uprising in a similar way. Over 11,000 police were deployed to repress the protests in Lima on the 19th of January. Two days later, tanks broke through the gates of San Marcos, and 193 students and provincial protesters were detained. Female detainees were forced to strip naked, and their genitals were searched for drugs.

As the protests continued in subsequent days, the police violently and consistently prevented the protesters from occupying public squares, in order to avoid images demonstrating the size of the movement. This steadily escalating police violence culminated on the 28th of January, when a protester was killed by a teargas cannister fired at close range into his skull.

The strategic fragmentation of the protests in Lima has facilitated claims by the government and the corporate media that the protests are the work of a small group of political agitators organized by narcotraffickers, foreign agents, and remnants of the terrorist group Sendero Luminoso. These unsubstantiated claims dehumanize the protesters, placing them outside the law and legitimating continued state violence in the provinces, with further police murders of civilians occurring in the regions of Puno, Cusco, and Arequipa. By the end of January, 47 people had been killed by the security forces since the start of the protests.

The universal humanity on the streets of Lima and across the country is thus being shattered by repression and erased by propaganda. Meanwhile US$53 billion of mining investments for 2023 are quietly announced. The prime minister of the new government holds unpublicised meetings with the heads of the main transnational mining companies operating in Peru, who are escorted to the Palace of Government by the various ex-ministers who they now directly employ. And the USA has expressed its support for Boluarte’s “efforts to restore calm,” while announcing $8 million of additional funding for her regime.

As I write these lines on the 2nd of February, Boluarte has just defiantly declared that her government remains “firm in our defence of democracy, stability, and private investment.” Meanwhile the protests in Lima finally seem to be petering out. Poor people can only survive for so long without working, and human beings can only suffer so much repression.

Have state and capital succeeded yet again in their joint campaign against the stubborn flourishing of universal humanity? Perhaps. But the Peruvian people have awoken, and any such victory can only be temporary and contingent. In the words of the Peruvian activist Indira Huilca: “What has arrived with this newly mobilized citizenry is the political agenda for the years to come, in which we must reconstruct a democracy shot to death.”

***

Japhy Wilson is Honorary Research Fellow in Politics at the University of Manchester and author of Extractivism and Universality: Inside an Uprising in the Amazon (Routledge 2023) and Reality of Dreams: Post-Neoliberal Utopias in the Ecuadorian Amazon (Yale University Press 2021). He is currently based in Peru.

This post was originally published in Spanish in OpenDemocracy.

Featured image credit: Wikimedia Commons.