By Aunindo Ghosh.

The symbolism and hidden messages of injustice lurking beneath the apparent success story of water governance in Bangalore, and a work of art which proved stronger than statistics in shifting perceptions around water and its politics.

Source: Art in Transit

Water, Me and a Mural

It was a hot summer afternoon in Bangalore, the showcase Silicon Valley of India. I was with a group of climate action fellows trying to understand the water issues of the city. Throughout the day, we visited a rejuvenated lake and a state-of-the-art sewage treatment plant. We also spoke to people who were at the forefront of solving water issues in the city., Their actions seemed to have worked, as despite the doomsday predictions of Bangalore approaching Day Zero within this decade, in my condominium, I had 24 hours water-on-tap, my drinking water tasted sweet, and I had never seen grey water or experienced the stench. In fact, unlike other environmental and climatic parameters like bad air-quality and rising temperatures, on this my city seemed to be doing fine.

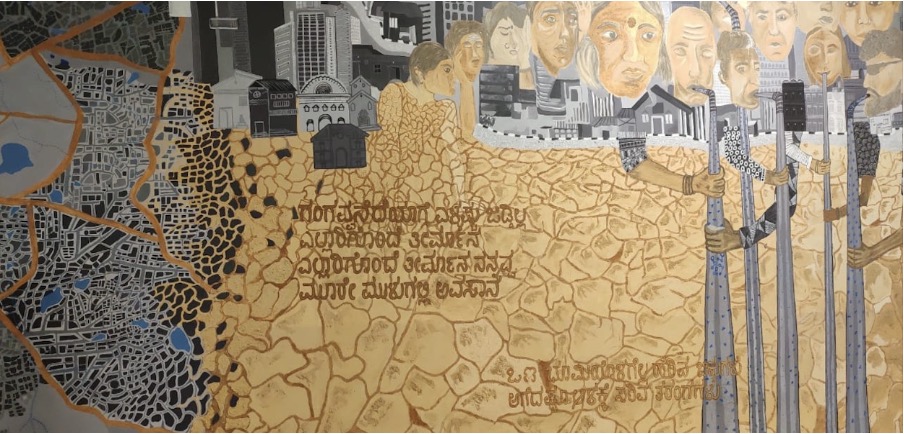

Our next stop for the day was Cubbon Park, the site of a rainwater-harvesting project. On our way, we were suggested by the tour leader to have a look at a Mural telling the Water Story of Bangalore created by a group of students-activists from the “Art in Transit” movement . By then, my head was reeling from the summer heat and from all the numbers and technical terms thrown at us earlier at the treatment plants, so I decided to just take a customary walk by the murals – and then I saw this:

Bigger the money, thicker the pipe! Mural at Cubbon Park Metro Station. Source: Pooja B, used with permission.

The frame above was almost hidden amongst the long series of illustrations – but there was something so deeply disturbing about it, that it caught my eye instantly. The rapidly urbanising Google Earth-like image on the left, almost merging into the parched earth on the right, to show reality from above and below – two sides of the same coin. The highrises and buildings signifying the so-called “development” and the rapid urban migration that happened along with it. Men of higher castes and upper economic classes drilling the earth with ever-thickening and ever-deepening pipes, sucking the common water table dry, while the less privileged ones – dispossessed and disenfranchised- helplessly look on! And to complete the picture, there is the quintessential middleman, acting as a conduit, with a pipe connected to both his mouth and head. Was it by accident that most of the people who looked on were women, with the ones most distant from water access being closer to the ground, almost becoming one with the earth? What was this frame doing in the middle of Bangalore’s successful water management story? What was the cost of this success?

I had to dig deeper and find out.

Accumulation by Dispossession: Unequal Access to Water and related Health Impacts

Bengaluru, predicted to be the fastest growing city in the world for the next 15 years, is already facing an acute water crisis. This has led to an ever-increasing demand for water, and local government bodies haven’t been able to keep up. 110 villages that got merged into expanding urban sprawl back in 2007 have no public water supply to this date . Moreover, in the areas in central Bangalore where there is municipal water supply from nearby Cauvery river, the property prices are so high that only the elites can afford to buy land, or rent houses. Others simply sell-off their lands and move to the suburbs, where there is no public provision of water.

The water demand gap is filled up by private water tankers, which operate without trade licences, and charge exorbitant amounts, especially in peak summer heat, benefitting by the lack of proper price regulation and their monopoly over the business. The Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) – The institution tasked with regulating this business hasn’t issued a single trade licence to date. The source that these businesses use is groundwater, which also is in great scarcity. The Karnataka Ground Water Authority is responsible for issuing permits for digging of borewells in the state. Within Bengaluru, the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) has been charged with this task. However, since 2017, no permits for commercial borewells have been issued by the authority, claiming dangerously low levels of groundwater in the state. The tankers, as a result, draw thousands of litres of water daily from domestic or illegally dug borewells. The fact that these two institutions do not always communicate and cooperate on the ground, results in a complete lack of oversight on the price, safety, and drinkability of the water.

The native villagers, migrant workers, and other low-income and marginalised citizens spend a disproportionate amount of their home budget just for water, while it hardly makes a dent in the pockets of upwardly mobile white-collar populations staying in gentrified colonies. Research has also shown that water crisis and micropolitics around water access has a deeply embedded gender aspect, where power and inequality plays an important role in affecting women disproportionately. Perhaps, not by coincidence, the lady in the mural that was placed farthest from the water source had a parched motif painted all over her body.

Even after ill-affording drinking water from the organised water-cartel, the worries do not end. Groundwater levels in Bangalore have depleted up to 1500 feet due to drying up of shallow aquifers resulting from illegal over-mining. As a result, heavy metals, harmful chemicals and sewage residues get into the water resulting in severe kidney problems, cancers, blue baby syndrome and dental ailments. The rich and the gentrifying can afford sophisticated water-filters and even bottled water, while the financially disadvantaged classes suffer. There are few cases of local politicians supplying clean filtered water, but that too is uncertified, unregulated, and fraught with vested business interest, re-routing of public money, and political advantage-seeking tactics.

India’s Silicon Valley, and it’s Water Mafias

My first brush with the disempowerment of civil society and the water-cartel came last summer, when our water prices suddenly went up by 30%. When, as an apartment owners association, we confronted the water-tanker operator, we were directed to the “real owner” who turned out to be the local legislative assembly leader who was running this as a shadow business. Frustrated, we approached the municipal authority for a resolution. To our shock, our water supply lines got stalled within 24 hours and we got a call from the politician saying that his people were everywhere, including civic authorities – and hence, we should just stop “meddling”, and pay the increased price. The term “Water Mafia” became very real for us.

In the paper titled ‘Mafias’ in the waterscape: Urban informality and everyday public authority in Bangalore‘ published in the journal Water Alternatives, Malini Ranganathan argues that rather than seeing the mafias as filling a gap where public water supply has failed, they must be seen as formative of the post-colonial state and not as existing apart from it. As she highlights, the actions of mafias must be understood beyond the profit and rent seeking behaviours normally associated with private tanker operators. Rather, social protection, the provision of welfare, electoral lobbying, and the facilitation of unauthorised land sales to lower middle class buyers are all part of the mafias’ political activities.

In exploring the political ecology of the commons, Massimo De Angelis has argued that enclosure is not a static historical phenomena, but a continuous process that feeds capitalism’s need for accumulation and creation of surplus value. In the case of Bangalore, , the water mafias are also land sharks who buy large parcels of land from the fringes of rapidly urbanising suburban Bangalore. Then they dig borewells pumping out the aquifers -a water commons, and sell the extracted water to the dispossessed poor and gentrifying rich alike, at an unregulated price. This accumulation perpetuates an accumulation of their power and profit, feeding a continuing cycle of inequality and urban injustice. The fact that the poor are priced out of the areas with municipal water supply, while also driven out even from suburbs with relatively higher water tables by water-mafias, is also a classical case of accumulation by dispossession.

Source: Bangalore Mirror

Source: Bangalore Mirror

Droplets of Hope – The million recharge well project

The story of Bangalore’s tryst with water would not be complete without mentioning the innovative “Million Recharge Well” project, conceptualised by the consultants at Biome Water Management, whereby shallow recharge wells are being dug in both private areas and public spaces in order to recharge the shallow aquifers, which have dried up not just because of over-mining, but also due to the increased concretisation of the city, resulting in reduced percolation of rainwater. This project has the dual benefit of reviving the lost livelihood of the ‘Mannu Vaddars’, who are traditional well-diggers. While this kind of project and initiative offers a ray of hope, I would argue that the core political-ecological issue of unregulated private water supply cartel, and resulting inequality and injustice, remains to be addressed.

Source: Art in Transit Project

The Role of Art, when statistics fail

In our life full of information and data overload, it is very easy to get desensitised to any statistics or dry information that does not affect us directly or immediately – even if it sounds ominous in the not-so-distant future. The alarms of Day Zero in Bangalore did not manage to get to me, as long as I had water coming out my tap, or the water filter was full. Bumping into the mural on that sultry afternoon, though, suddenly highlighted the invisible injustices behind my convenience. The symbolism and hidden messages of injustice lurking beneath the apparent success story left a strange taste in my mouth. A work of art ended up being stronger than statistics, and it forever changed my perception of the water I took for granted.

* Aunindo Ghosh is a seeker of truth through the lens of intersection between environment, society and economics. He is a political ecologist and public communicator by training, and works in the field of Public Engagement & Outreach for climate action in India. Aunindo is an alumnus of Institute of Environmental Science & Technology (ICTA) at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain.

A very interesting and horrifying factual analysis by Aunindo. The “helplessness of the situation” is even more disturbing. How can mankind be so insensitive! How long shall we be digging our own graves! It’s already too late! May God grant the human species with wisdom and common sense!