By Meriem Farah Hamamouce and Amine Saidani

The agricultural sector in Algeria relies on the informal labor force of Sub-Saharan migrants on their way to Europe. Interviews with migrants highlight their precarious conditions of life and work, worsening during the Covid-19 health crisis.

Introduction

Over the last few decades, the Maghreb has become a migratory space: in addition to its traditional function as a site of emigration, it is now a transit land for many migrants trying to reach Europe. Since many African countries are dealing with unstable political and economic situations as well as with climate change, the in-flux of sub-Saharan migrants has become a major societal fact in Algeria. While in the 1990s, this concerned only the Saharan regions, during the 2000s it spread to the coastal cities of the north of the Maghreb, feeding the local economies. Transit through the Algerian territory happens in stages and through specific corridors. Although transnational migration to Europe begins in a heterogeneous manner, sub-Saharan migrants reorganize themselves collectively during their journey. During different stages of their journey, migrants ‘recognise’ each other and cooperate, gradually creating a common history, an ‘adventure’: their migratory project is a collective one and brings them together (for more information on sub-Saharan migration through North Africa see the book “Le Maghreb à l’épreuve des migrations subsahariennes. Immigration sur émigration” edited by Bensaâd, 2009).

According to the report “Contribution à la connaissance des flux migratoires mixtes, vers, à travers et de l’Algérie: Pour une vision humanitaire du phénomène migratoire”, compiled by the International centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD) in 2015, the province of Ghardaïa is an unavoidable transit land for migrants. They settle temporarily in order to accumulate the financial resources and information necessary to reach Europe. This reality is evidenced in the strong presence of migrants in the informal labor market in the Sahara, particularly in sectors with labor shortage, namely in agriculture, construction and public works. In recent years, sub-Saharan undocumented workers have become essential to the functioning of these sectors.

However, the introduction of a range of measures to limit the spread of Covid-19 has disrupted this migration process. In light of the context and our previous work with different rural actors, including sub-Saharan agricultural workers in the M’zab Valley, we explored how they dealt with the constraints posed upon them by the pandemic. In other words, how did sub-Saharan migrants experience the pandemic and the related lockdown measures? How did these impact on their work and which coping strategies did they adopt? We answer these questions by placing the experiences of young sub-Saharan migrants at the heart of our qualitative analysis. Because of the structural role of sub-Saharan labor particularly in Saharan agriculture, we focus on this sector and have made some recommendations for policy that could contribute to more a just development of this sector.

The M’zab Valley

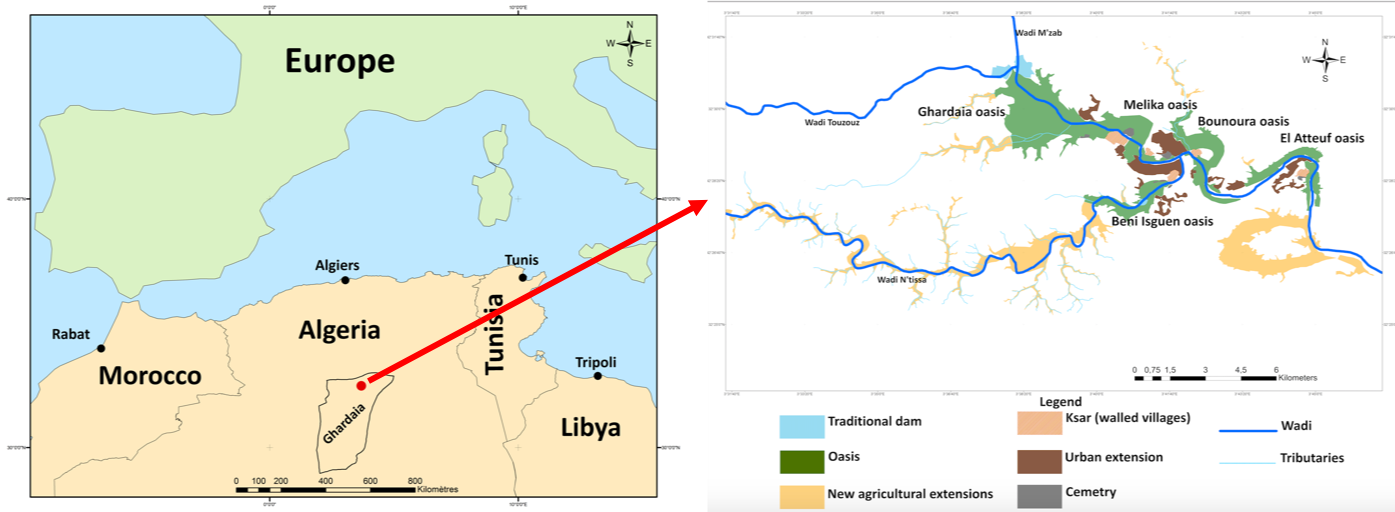

The M’zab valley is located in the province of Ghardaïa, in the northern Sahara, about 600 km from the capital Algiers, and is characterized by the coexistence of two agricultural landscapes: the ancient palm groves created in the eleventh century and the new agricultural extensions created in the 1980s. The labour force is mainly composed of sub-Saharan migrants in transit.

Map of the M’zab valley case study in Algeria. Source: Meriem Farah Hamamouce

This study is based on our work prior to the pandemic with agricultural actors in the M’zab valley. During the month of March 2021, 10 interviews were conducted with sub- Saharan workers in order to document their experiences during the Covid-19 crisis.The names of the sub-Saharan farm workers interviewed are fictitious in order to maintain their anonymity.

From Mali to Ghardaïa, a long and difficult journey

The Malian border is more than 1200 km away from Ghardaïa. The migrants we spoke to underlined the reasons for crossing the border. One of the migrants we interviewed, Djamel, 22, told us:

“I left my country, Mali, because life is difficult and we cannot find work… In Mali, there is almost no work left because of the civil war and the pay is very low, around 3 euros for a 9-hour working day… the search for gold is hard work with a lot of risk, without guaranteeing any money at the end of the day“.

Another migrant, Nassim, 24 highlighted the difficult conditions of the journey:

“We had to walk for hours in the middle of the desert while avoiding the main roads in order to avoid the Algerian security service who are very present in the border regions… Algerian smugglers show us the way in exchange for money… So to pay for our journey from the Malian border to Ghardaïa, we are obliged to stop in certain towns to earn a little money… part of the money is used to pay the smugglers and the other part is sent to our families who stayed in Mali through an informal network of money changers… our families rely on us to provide for them“.

One of the Malians interviewed, Karim, 23, said:

“I am the eldest of 10 children… My father has a low income… he relies on me to feed the family… that is why the goal of going to Europe is not achieved quickly… We have to meet the needs of our families first.

Over the years, an informal network of money changers has developed between Algeria and Mali. As a young Malian, Said, 20, explained:

“If I want to send the equivalent of 10,000 DA (± 63 €) in Francs to my family in Mali, I have to give 17,000 DA (± 106 €) to the trader”.

The choice to settle in Ghardaïa and not in another Algerian province is mainly explained by family ties:

“My older brother settled in Ghardaïa since 2014…he welcomed all the young men from the family and from our home village who wanted to embark on the adventure of migration…we need a stable focal point before we embark…because this is the person who takes care of us once we are arrive and waiting to find a job…he also puts us in contact with employers“.

Karim added

“My brother worked for years with a farmer-digger… when he went back to Mali temporarily, he gave me his contact… I came directly to him in 2019“.

This choice to go and work in Ghardaia can also be explained by the need for labour, as explained by a young Malian, Yacine, 20:

“I came here to Ghardaia because work is available and the pay is better… During my journey, I stopped first in Bordj Baji Moukhtar, a border region with Mali, where I worked for 1000 da/day, then I went to Adrar where I worked for 1200 DA per day (± 7,5 €)… here in Ghardaïa, we are paid between 1500 and 1700 DA per day (± 94 and 106 €)“.

Bypassing checkpoints during the lockdown

Migrants have taken an important role in the development of the national economy despite their irregular situation in Algeria. In case they are stopped, they risk being escorted back to the borders. With the Covid-19 health crisis, control has been reinforced, which has led migrants to develop strategies to avoid coming across the checkpoints. The 10 migrants we interviewed told us that they used secondary roads, wadis and mountains to move between their homes and workplaces. As Djamel explained:

“I chose to work on a remote farm in Ghardaïa in order to ensure my safety…to get to the city center, if necessary, I cross the gardens and farms in order to avoid the controls“.

A migrant cycling through a wadi to avoid checkpoints. Photo: M. F. Hamamouche

This irregular situation makes migrants vulnerable. Some take advantage of the situation of Malian migrants by refusing to pay them when their work is completed, while threatening to call the security service. Migrants are also subject to repeated theft, not only by some Algerians but also by migrants from other countries. As Salah, 25, confided to us:

“I was attacked when I tried to bypass the town on the side roads. They stole my phone, my bike and my money for the day“.

According to the same person,

“attacks and thefts have increased since the beginning of the Covid-19 health crisis… These attacks are carried out with impunity… the aggressors know that we cannot file a complaint“.

Gathering sites have been replaced by word of mouth and phone recruitment

Before March 2020, migrants looking for daily work used to gather in specific gathering points. Farmers used to come and recruit them in these places. However, with the health crisis and the reinforcement of checkpoints, migrants deserted the collection points. To find work, they could only rely on word of mouth and through phone contact, as Karim explained:

“During the first months of the lockdown, when mobility restrictions were strict, I was able to find work thanks to my network of contacts. My former employers, who had kept my phone number, contacted me when they, their family or neighbors needed a worker”. Another worker, Nassim, 24, told us: I took the initiative to call my former bosses, one by one, to ask them if they needed a worker. Only the farmers responded positively to my request… the building contractors did not need any more workers since this sector was heavily impacted by the health crisis”.

On the other hand, for migrants who arrived in Ghardaïa shortly before the health crisis, it was more difficult to find work because of the restrictions imposed by the government to counter the spread of Covid-19. They relied on their compatriots who had been in the M’Zab valley before them. As Adam, 18, explained:

“I arrived in Ghardaïa in February 2020… I was able to find a job quickly and even during the lockdown thanks to a young man from my native village who has been living in Ghardaïa since 2018. He contacted me every time his employers needed several hands”.

Some of those who did not find work during the months of the lockdown, relied on help from their compatriots:

“I borrowed money from a friend… then I paid it back a few months later… fortunately there is mutual aid and compassion between Malians… in my opinion this is what makes the difference with other migrant nationalities” (Ilyes, 19).

Turning to agricultural work and a strong demand for versatility

Migrants who worked in the construction and public works sectors before the health crisis saw their activity suspended when the lockdown measures were implemented in March 2020. This economic sector has been hit hard by Covid-19. To support themselves and their families back in Mali, some of them have turned to agriculture. According to Nassim:

“Before the crisis, I worked mainly in masonry, but with the introduction of the lockdown and the suspension of all building activities, I found myself without work… I then became an agricultural worker because this activity cannot stop… The farmers needed us to carry out certain agricultural tasks: working the soil, irrigation, manual weeding, harvesting seasonal vegetables… we found work by word of mouth”.

Agricultural tasks carried out by sub-Saharan workers. Photo: M. F. Hamamouche

Another worker, Salah, told us that he had been recruited to help clean out wells:

“A friend, an agricultural worker for a farmer- washer, called me to tell me that his employer was looking for workers with knowledge of construction and public works to restore a dozen wells in an old oasis… I responded positively to this proposal because I knew that this type of work would last several months“.

In addition, there was a high demand for multi-skilled workers during the lockdown period, as farmers were looking for Malian workers with skills in agriculture and construction, as was the case for Mohamed, 23:

“When my employer called me on the phone to recruit me, he had asked me if I had any knowledge in construction, as he wanted to fence his farm and do some work in his secondary house so that his family could confine themselves… he had specified that the work also consisted of maintaining the garden… he had offered me free accommodation in the farm during the work as his family was not yet there”.

Agricultural tasks carried out by sub-Saharan workers. Photo: M. F. Hamamouche

More responsibility for skilled agricultural workers

Migrants who have been working in the agricultural sector in Ghardaïa for a number of years, have seen their responsibilities increasing in the farms, particularly in the phoeniculture sector. Indeed, the mobility restrictions imposed by the Algerian state to counter the spread of Covid-19 during 2020 have had an impact on the availability of skilled agricultural workers for harvesting dates. Traditionally, date harvesting in the M’Zab Valley, and particularly the harvesting of Deglet Nour dates, relies on workers from the Timimoun region, some 600 km away. The workers specialised in harvesting dates belong to a socio-ethnic group descended from the slaves who worked in the M’Zab valley. The latter were formerly called “khammès”, which means “sharecropper to the fifth” because they worked the land in exchange for a fifth of the harvest. Most of the descendants of the khammès gradually returned to their native region (Timimoun) after the 1971 land reform –a decision implemented to distribute land to landless peasants and to change the social status of the descendants of the khammès (for more information see Aït-Amara, 1999).

However, in October 2020, these skilled workers were unable to travel to the M’Zab valley due to mobility constraints. Consequently, Malian workers benefited from this situation. As Samir, 25, said:

“I have been working as a farm laborer since I arrived in Algeria in 2017, and I never went near the palm tree until 2020…the farmers preferred to use skilled workers to harvest the dates which have a high market value…but with mobility restrictions and the low local availability of skilled workers, they turned to sub-Saharan migrants as a last resort”.

Conclusions

In the Sahara, agriculture continues to be the main sector of occupation for migrants. However, its socio-economic role has evolved. It has gone from being a seasonal supplementary job in the traditional oases of the border areas, to an essential activity in new forms of Saharan agriculture.

Indeed, the unlocking of access to groundwater and agricultural land from the 1980s onwards allowed the development of large ‘pioneering front’ type agricultural projects, occupying new land and renewing agricultural methods and practices (see also the article “From Oasis Archipelago to Pioneering Eldorado in Algeria’s Sahara”, by Amichi et al., 2018).

In the Algerian Sahara, where less than 11% of the Algerian population lives (3.6 million inhabitants), agricultural development would not have been possible without foreign labor. Although irregular immigration is neither formalized nor controlled by the state, it has become structural to the functioning of strategic sectors and to the national economy.

Paradoxically, this pervasive reality, which puts immigrant agricultural workers in even more vulnerable conditions regarding their labor and health security and rights, is officially concealed, albeit tolerated to varying degrees depending on the area, the different sectors of the economy and the economic or political conjuncture. The ambiguity surrounding this migration (partially tolerated but not recognised) and the fragility of the conditions of residence and work, which inevitably lead to situations of vulnerability (e.g. blackmailing of employers controlled by the security services) are accentuated in times of crisis.

This situation more than ever highlights the importance of politically recognizing the rights of migrant workers and of taking action to address their needs. The migrants we interviewed told us that the conditions in which they are living and working are not dignified. The regularization of seasonal work and the allocation of work permits to foreigners would allow them to claim fundamental rights (social, economic and civil).

This issue of recognition must be given special attention by public authorities. A better understanding of the dynamics of migration and employment in Saharan agriculture can help to inform policies and regulations to reorganize the recruitment and employment of migrants and ensure decent and dignified working conditions. Policies must address the precarious situation of these workers focusing on providing them with proper housing, secure living conditions and health assistance. Moreover, little information is available on the impact of COVID-19 on the health of the immigrant workers.

Meriem Farah Hamamouce is a junior water management and agronomy researcher. She is the founder and manager of BRDA (Agricultural Research and Development office) and an associated researcher at G-Eau Research Unit (France). She also works as an independent consultant for the engineering office (ECA) in Algeria.

Amine Saidani is founder and manager of an engineering office (ECA) in Algeria and a Ph.D student in water sciences at IAV Hassan II (Rabat, Morocco) and SupAgro (Montpellier, France).

One Comment