By Margarita Triguero-Mas and Mario Fontán-Vela

Despite Portland’s reputation as a champion of sustainability, the city still struggles to overcome its legacy of racist policies and environmental injustice when it comes to the inclusion of Black residents.

Editors’ note: This post forms part of the series “Green inequalities in the city”, developed in collaboration with the Green Inequalities blog. The series seeks to highlight new research and reflections on the linkages between the dominant forms of “green” redevelopments taking place in cities and questions of urban environmental justice, and the challenges and possibilities these imply for more just and ecological urban spaces.

Portland is considered a pioneer of sustainability planning. However, its traumatic history of racial exclusion, and environmental injustices and increasing gentrification have drawn criticism for perpetuating white privilege, and have raised concerns about procedural justice linked to environmental interventions in the city. In Cully and several other neighborhoods, community groups are leading new anti-gentrification policies and sustainability projects that acknowledge the risks of (environmental) gentrification. But while some of these initiatives are the result of the Black/African American community’s mobilization, their inclusion in the decision-making process is still largely insufficient to produce truly equitable and just outcomes.

Portland’s sustainability as a source of gentrification and exacerbated inequalities

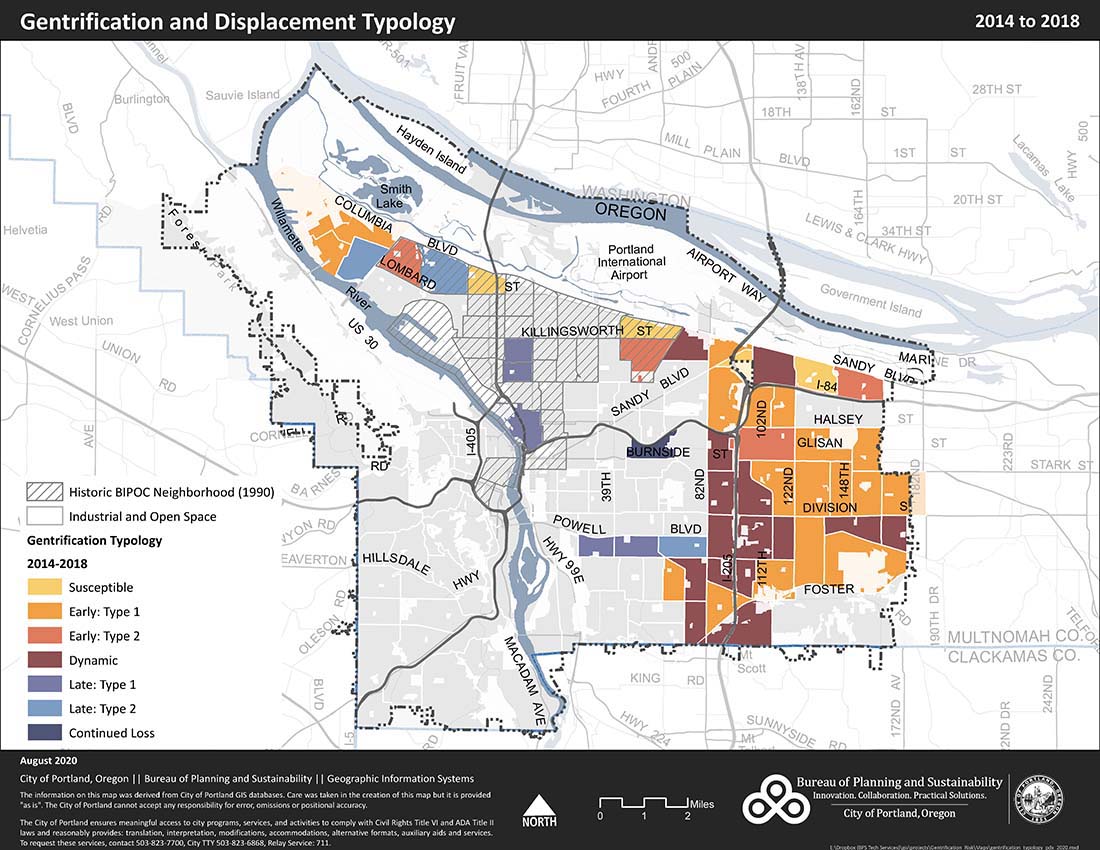

One of Portland’s widely known examples of institutional racism towards Black residents is the case of the Albina District, located in the inner North/North-East. After the initial confinement and concentration of the Black/African American population, through racist policies such as redlining, the area was subject to the construction of infrastructure (Interstate 5, Highway 99 and Memorial Coliseum, and the expansion of Emanuel Hospital) that erased substantial parts of the District, destroying key African American landmarks, shops and homes. Gentrification pressures later caused the community to scatter throughout Portland, with detrimental effects on community identity and place attachment. Many Black residents express a strong attachment to Albina as the heart of the African American community, even those who no longer live there.

Main square of Albina District, historically a meeting point of the Black/African American community. Informative panels through Albina District describe the history of the neighborhood, from which the Black/African American community has been disproportionately displaced.

Construction sites abound in the Albina District, which is currently characterized by a mixture of historical Victorian houses and modern luxury housing.

Meanwhile, building on its reputation for livability and climate change mitigation initiatives, Portland has branded itself as a sustainable and green city. But a closer look reveals that industrial pollution and environmental hazards have been and still are higher where unprivileged residents (such as Hispanic, African American or Asian) reside, disproportionately impacting groups living below the poverty line. In 2015, an estimated 600,000 residents lacked regular access to some of the main sustainable features that Portland markets itself on: fresh and healthy food, safe neighborhoods, convenient transit and affordable housing. This raises concerns about how sustainability is defined and conceptualized by the city, indicating that the city’s focus on environment and economy may lead to a growth-obsessed model of sustainability that neglects societal needs.

In fact, environmental amenities and sustainability projects have largely manifested as large-scale, mixed-use projects that have attracted tech companies and middle-class residents, resulting in an exacerbation of inequities, rising real estate prices, eviction, gentrification and the displacement of long-term underprivileged residents, particularly Portland’s Black/African American and the Latinx community. In fact, those interviewed for our GREENLULUs research project expressed concern that environmental decisions and development priorities in Portland have been made mostly by white male experts, leaving low-income and people of color consistently out of the decision-making process.

Municipal and neighborhood initiatives to tackle environmental gentrification

Our fieldwork indicates that municipal representatives and technicians are ill-equipped to enhance sustainability without triggering environmental gentrification. In contrast, some bottom-up strategies, like those developed in Jade District and Cully neighborhoods, are precisely designed to avoid gentrification while enhancing sustainability.

In Jade District, an ethnically and racially diverse neighborhood located in central East Portland, the community-led initiative Portland Ballot Measure 26-201 (known as the Portland Clean Energy Initiative) taxes large retailers in order to fund activities like green job training programs and energy-efficient home upgrades that prioritize low-income residents and communities of color. This increases job opportunities, potentially income levels, and housing quality for long-term low-income residents, enhancing their odds to remain in the neighborhood.

Another example lies in Cully in North-East Portland, one of the city neighborhoods with the least non-Hispanic white population, and a disproportionate concentration of subsidized, low-income and working-class renters. Here, reconceptualizing environmentalism as a movement that should benefit the community, has led to the branding of Cully as an EcoDistrict where sustainability is also an antipoverty strategy. To prevent the displacement of residents by green gentrification, community organizations mobilize to provide affordable housing and affordable economic elements in the neighborhood. For instance, the initiative “Living Cully weatherization + home repair project 2.0”, was initially conceived to lower energy bills by upgrading homes to low-cost energy systems, and ended up repairing household mold, failing roofs and heating systems. And the Thomas Cully Park, was a former landfill that was turned into a park in 2012 thanks to a coalition of neighborhood organizations called Let us Build Cully.

General view of Thomas Cully Park. The park features areas such as a gathering space designed for the Native American community, a playground area with water pump (main photo) an a vegetable garden.

The anti-environmental gentrification strategies in Jade District and Cully were generally perceived by the people we interviewed as strategies adaptable to Portland city and beyond. Notably, despite the lack of Black/African American leadership in these current strategies, the African American community has been extensively involved in anti-gentrification policy work and community mobilization in Portland, achieving wins such as the non-cause evictions ban and the inclusion of several Anti-displacement PDX demands in the Master Plan of Portland 2016.

Still, the concerns raised by our interviewees over institutional racism, and the lack of African American leadership and of significant involvement of this community in grassroots anti-environmental gentrification strategies, constitutes a major challenge in Portland’s fight against environmental injustice, displacement and gentrification. Portland must find an alternative to a growth-obsessed model of sustainability that integrates social concerns.

—

Margarita Triguero-Mas is a transdisciplinary researcher focused on healthy, equitable, resilient and sustainable urban planning. She addresses her work through approaches mainly derived from public health to better understand the health effects of air pollution, green and blue spaces, and meteorology, both in high and low-income countries. @ItaTrigueroMas

Mario Fontán Vela is a public health and preventive medicine doctor and a doctoral researcher at the University of Alcalá. His research explores the relationship between the urban environment and the population’s health, focused on how cities can promote physical activity through green spaces, based on the social determinants of health frameworks.

All photos taken in July 2019. Credit: BCNUEJ.