By Jeroen Vos and Rutgerd Boelens

Transnational water movements often mutually complement with place-based forms of collective water management. This may enhance grounded and equitable water provision, and shape political advocacy of common resources control at multiple scales. This is the latest post of the series “Reimagining, remembering, and reclaiming water: from extractivism to commoning”, co-organized with the FLOWs blog from IHE Delft Institute of Water Education, looking at struggles over more just and ecological water presents and futures.

All around the world, people have organized themselves to build, run, maintain and defend collective water provision. This water can be for household consumption, irrigation, micro-hydropower, fish production, or for other uses. People have also organized to protect their river, lake, wetland or catchment area. Different bodies of scientific literature exist on these water collectives, of which two stand out. One body investigates the organization of so-called “common pool resources” management. Elinor Ostrom and others have described the factors that influence the functioning of initiatives around common pool resources. The other body of scientific literature focuses on social movements that mobilize against extracting or polluting industries, dams, and water transfers that destruct rivers.

We propose to merge these two theoretical perspectives while complementing and deepening them, with attention to and analysis of, among others, unequal power relationships; contingency; non-static cultural and political-strategic identities; contextuality; and the workings of subtle normalization and governmentality schemes. In our frame, beyond rational choice misfits, we acknowledge the political and cultural-symbolic character of common pool resources organizations, and at the same time we recognize the constructive action of water ‘protest and proposal’ movements.

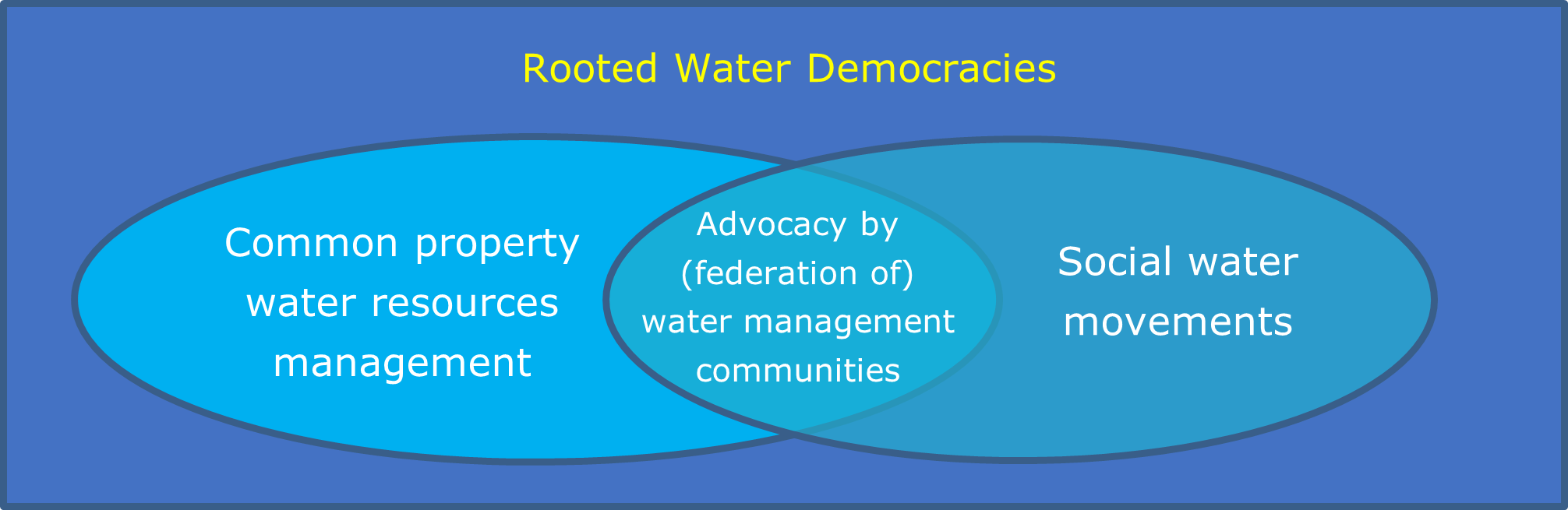

For this purpose, we suggest using the concept of “Rooted Water Democracies” (RWD). RWD can be collectives that manage a shared water resource, or a group of people that advocate for more inclusive and sustainable water policies (see Vos et al. 2020). In some cases, these collectives stand for both, or they shift their focus from managing a common water resource towards advocacy, or the other way around (see figure below). To defend and advocate common water resources management, local water users’ collectives often organize themselves in second tier and third tier advocacy organizations.

Schematic representation of Rooted Water Democracies, interlinking social movements and communal commons governance. Source: Vos et al. 2020

Out of numerous cases around the world, we give two examples of social water movements that organized themselves around collective management of their own water resources. The first example is the social movement called K136 in Thessaloniki, Greece, that protested against the privatization of EYATh, the Thessaloniki Water Supply and Water Sewage Company, in 2011. The movement proposed to buy the company, financed by the collective of water users, thus turning the protest movement into a common property water resources management collective. K136’s proposal was that if each household paid €136, one non-profit cooperative per municipality – 11 in total – would be in charge of the water. This plan was not realized. A minority share of the water company EYATh was privatized and the anti-privatization movement got divided in a faction promoting the ideal of the communal ownership and a faction promoting the public (state) management of the water company (TNI, 2014).

The second example is the Kengrehalla Rejuvenation Movement (KRM) in Karnataka, India, which was more successful. This movement first mobilized local people to protest against water transfers from rural areas to the town of Sirsi, for the building of a dam. After the success of stopping the dam, the organization shifted towards improving local water management and watershed conservation activities by creating the Kengre Watershed Protection Committee, that promoted rain water harvesting, tank cleaning, awareness raising and reforestation with native species (SOPPECOM, 2010).

Katribu nation holds an anti-dam protest in the Philippines. Dams, mining and privatization of drinking supply are recurrent threats to the water and livelihoods of rural and urban communities across the globe. Source: International Rivers / Water Alternatives

There are also many examples of initiatives that shifted from common property water resources management to advocacy and resistance. A first example are the water users’ associations that manage large-scale irrigation systems in the North Coast of Peru. They manage their systems relatively successfully. One threat to the agricultural production, however, is the contamination of rivers by mining operations in the headwaters. On various occasions the water users’ associations have mobilized large protests against new mining projects. A second example are the local water collectives like water associations, village committees or cooperatives, which manage rural drinking water supply in many countries around the world, such as Benin, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, India, Colombia or Sri Lanka. They have often organized around regional federations and national organizations in order to defend their interests (Dupuits et al., 2020).

Another example is provided by Hoogesteger et al. (2016) who examine cases in Ecuador where drinking water and irrigation collectives integrate and unite at district, regional and national scale, challenging the state’s formalistic water governance structures. They organize to defend their water use rights, enforce government accountability, and promote conservation of headwater areas. A last example are the North African farmers’ collectives that manage oasis, and that have organized a federation called RADDO in 2001 to advocate for the protection of the oasis, which are under threat due to the depletion of the aquifers by large-scale water users outside the oasis.

These are just a few examples of the many different forms RWDs can take, showing the mix of on-the-ground managing water resources and multi-scalar advocacy work. In our book Water Justice, published in 2018, we describe many more instances of the diverse collective action forms to defend and create inclusive, democratic and environmentally sustainable water management. These experiences show that common pool resources management collectives often perform important advocacy work and shape alternative governance structures, at different scales.

National March for the Right to Water, began Feb. 1, 2012 from Cajamarca to Lima, Peru in protest against a large mining project. A month later, a similar March for “Water, Life and Dignity of the Peoples” was held in Ecuador.

RWDs are often under pressure. They are unseen or side-lined by government organizations. This is because governments and companies have interest in taking control over water resources, and their forms of collective management are often not accepted. For instance because their internal rules do not comply with (rigid and decontextualized) national legislation.

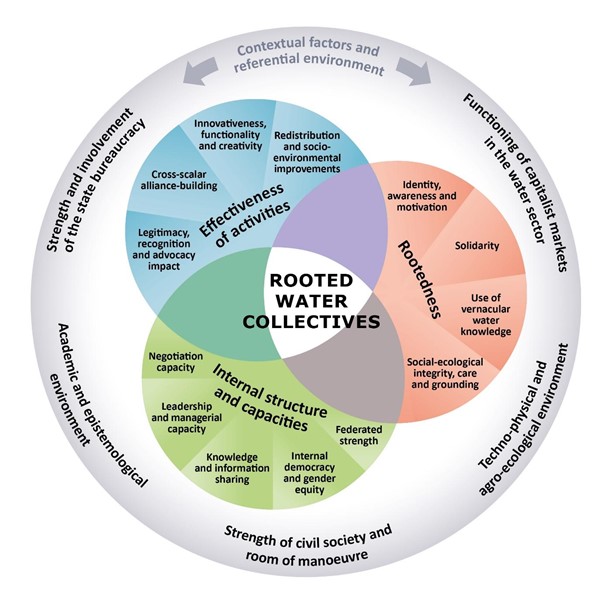

To better understand RWDs, we propose the look at three dimensions of RWDs (see figure 2 below):

- ROOTEDNESS: the rootedness is characterized by the use of vernacular and local knowledges, awareness, solidarity and caring for local socio-ecological integrity. Socio-ecological integrity refers to management of resources taking ecology and current and future generations into account.

- INTERNAL STRUCTURES AND CAPACITIES: these refer to the internal democratic organization, with respect for minorities, and good leadership and managerial capacities. The degree of federation is also important to assess. This also involves looking at how the local associations are organized at higher levels. They might be organized in first, second and even third tier federations.

- EFFECTIVENESS OF ACTIVITIES expresses the success of the RWD to defend their interests, negotiate with other stakeholders , and build alliances with other organizations like NGOs or government organizations .

RWDs do not always perform optimally on all three dimensions. Many forms of RWDs exist, and RWDs are not perfect democracies or intrinsically equitable institutions. It is also crucial to look at how local collectives, when engaging in transnational federations or mobilizations to defend their rights, often adopt and institutionalize global norms and modes of framing (e.g. claiming the “human right to water” or “rights of nature”, concepts that might be adopted to increase ‘resonance’ with policy makers and NGOs) .

This may be a strategic and creative process that often empowers locally grounded stakes and coalitions, but may also go against local understandings and rooted meanings and principles. As Dupuits et al. (2020:1) explain: “On the one hand, the appropriation of expert knowledge and technical idiom may improve their recognition and access to political and financial support. On the other hand, transnational involvement may (re)produce misrecognition or exclusion on the ground for community-based organisations”. RWDs will change over time, dynamically working along and connecting different spatial, institutional and time scales. Leadership, environmental and social changes often have large effects on the organisation of RWDs.

Schematic representation of Rooted Water Collectives analytical framework. Source: Vos et al., 2020.

To understand the internal functioning and success of a RWD, one should also regard the enabling and constraining environment in which they develop. This includes the state bureaucracy, wider economic circumstances, the agro-ecological environment, the strength of the civil society, and the societal acceptance and support of discourses about collective self-organization for managing commons. As the figure indicates, in our RWD framework, these 5 contextual factors and referential environment indicators get explicit analytical and institutional-political attention.

In this sense, the analysis is fundamentally different as compared to institutional analysis based on rational choice theory, in five ways:

- The analysis starts from the people’s struggles and empowering and justice effects of collective action.

- The analysis focuses on the socio-political and cultural-symbolic interactions, and not on the common resources units or any presumed optimal functioning of socio-ecological systems in and by themselves.

- Multi-layered RWD are regarded as politically federated organizations, rather than “nested” enterprises.

- The analysis regards the interactions of RWD with state bureaucracy, beyond the formal recognition by the state of the existence of common pool resources management. Civil liberties and political freedom are important factors needed for RWD to develop.

- RWD are not only about resources management rules and outcomes, they are about different worldviews, visions, values and believes regarding water sources and rivers, and their uses.

In conclusion, we propose to look at the real practices, organization and outcomes of collective water management, and how these practices are both contested and defended. Many different forms of collective water management exist in different contexts across the world: they are often unseen or side-lined, but critically important for water justice.

—

Jeroen Vos is associate professor at the department of Water Resources Management at Wageningen University, The Netherlands. His current research interests are the organization of riverine communities and the politics of water use by agribusinesses in Latin America.

Rutgerd Boelens is Professor Water Governance & Social Justice at the Dept of Environmental Sciences, Wageningen University, and Professor Political Ecology of Water in Latin America, CEDLA/University of Amsterdam. He also holds visiting professorships in Ecuador and Peru and coordinates the Justicia Hídrica /Water Justice alliance: www.justiciahidrica.org

Cover image: “Water is not for sale, it s defended!”. Artist: “Asociación de Educación y Comunicación La Cuculmeca”. Source: Red Latina sin Fronteras.

2 Comments