How can agrifood alternatives become part of activist strategies, which embody a politics of extending conflict and social struggle to confront the capital-state nexus, rather than just aiming at building difference or autonomy in the cracks of capitalism?

Source: http://foodtank.com

Alternative agrifood movements such as organic farming, fair trade, slow food, community-supported agriculture, and local food networks have proliferated since the 1990s worldwide. Arising as a critique and an alternative to the corporate control of agrifood systems, the industrial model of agriculture, and neoliberal globalization, they ask the fundamental democratic questions of what needs, rights and lives people recognize, desire and demand.

Localism and market-based activism, however, has undermined their transformative potential. Whereas some argue that alternative food economies create spaces for progressive discourse to imagine and create alternative food worlds, critics sustain that, without confronting political and economic centers of power, alternatives complement -rather than oppose- conventional agrifood systems, thereby, failing to address social inequalities. Do alternative food economies have any role in the radical transformation of the agrifood system?

Here I present two different examples that show how agrifood alternatives can be part of activist strategies, which embody a politics of extending conflict and social struggle to confront the capital-state nexus, rather than just aiming at building difference or autonomy in the cracks of capitalism.

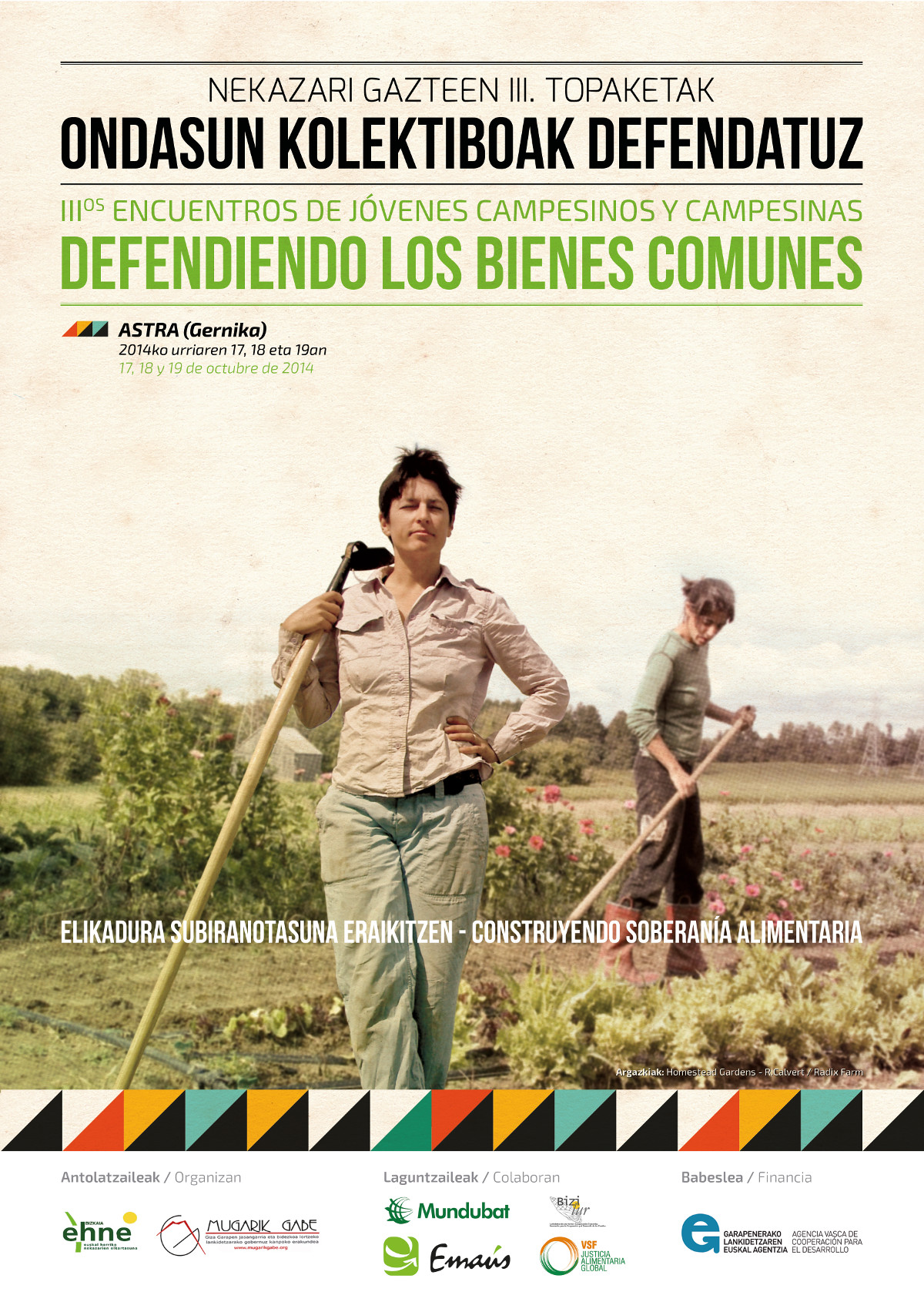

III Meeting of Young Peasants, October 2014, Euskal Herria. Source:www.elikaherria.eus

Building food sovereignty in the Basque Country

EHNE-Bizkaia is a union of small-scale farmers in Biscay, a province of the Basque Country, Spain. Born in 1976, it has a long history of political activism. Years of agrarian modernization oriented to an intensive, competitive and indebted agriculture were causing the increasingly abandonment and aging of the sector, as well the loss of agricultural resources. Keep focusing on prices, subsidies and policy reforms was felt as insufficient. A more critical approach to production models and economic development pathways was needed.

The union embraced then the goal of food sovereignty, based on new “peasants”, agroecological production and local food networks. Its goal was not just to respond to the survival needs of small-farmers, but to address their problems as a “social question” – how and what food produce, where and by whom and to who? This would allow small-farmers to speak for the whole of society and build broad social and political alliances, while envisioning an economic-agrarian alternative for the Basque territory.

How to translate this into practice? EHNE-Bizkaia stopped small-farmers’ training in conventional farming, and opened its discourses and activity to society (e.g. talking of food, rather than just agriculture; setting training offers to non-farmers; intensifying social information through publications, debates, etc). It developed the community-supported agriculture network Red Nekasarea, based in alliances between consumers and small-farmers. And gave primacy to attract new young agroecological producers in order to rejuvenate the sector and gain new potential militant energies.

The union’s concern, however, is not just to build practical alternatives in the “cracks” of capitalism or exemplify that another agrifood model is possible and better. Ideological work on the emancipatory agenda of food sovereignty is fundamental to policitize agrifood issues in society. Importantly, the building of practical alternatives is followed by the perspective of their convergence into a broad social movement struggling for food sovereignty in the Basque territory. While led by small-farmers, this movement is built on the basis of alliances with other social and political forces.

Building alternatives on the ground and uniting them into a social movement is followed by struggles to change policies and institutions. For instance, the struggle for land reform is a main stage of confrontation with the state. Land access is a major problem to young producers. Land reform is envisioned as a mean to ensure food production according to social needs, not market dynamics. The state then is called to be the sovereign power that has to ensure land is used according to its social function of providing food, regardless of the property regime. Nonetheless, this is not a call to top-dow approaches. For EHNE-Bizkaia, the state should be transformed from the bottom-up.

No-middlemen food distribution in Greece. Source: http://greektv.com

Building solidarity in food distribution in crisis-ridden Greece

Global economic crisis and austerity policies have hit Greece hard, especially since 2010. Economic meltdown was accompanied with the withdrawal of welfare policies, growing levels of unemployment, poverty and social inequalities. In the midst of social hardship and mass anti-austerity protests, solidarity networks arose to respond to immediate basic needs, expand resistance struggles and offer alternative pathways that re-think the economy and democracy.

For the first time in decades, food consumption declined. Signs of hunger and nutritional poverty were evident around Greece, while relative prices of food kept increasing. As charity, philanthropy, entrepreneur ventures, and neonazi xenophobic actions (food banks only for “genuine Greeks”) on food were increasing, social activists engaged in building alternative food distributions based on “solidarity”, i.e. equal relationships.

After the flowering of grassroots solidarity food banks, soup kitchens, and social groceries, the ‘no-middlemen’ food distributions emerged in 2012. Such open-air distributions bypass intermediaries, providing better prices and direct payment to farmers and quality food at low cost to impoverished consumers. They are organized by local solidarity groups that select farmers on the basis of quality and price criteria, frequently asking them to give some % of their produce for free for poor households.

The first initiative appeared in the town of Katerini, in Central Greece, and rapidly spread across the country, especially in Athens and Thessaloniki where food deprivation is higher. Many of the existing 50 local groups, are also involved in other solidarity actions in health and education. Most of the groups organize convivial and political activities in their neighborhoods and get involved in local struggles such as against electricity cuts and public services privatization.

Apart from responding to the basic needs of consumers and supporting farmers, a central aim of these initiatives is to re-construct the economic along solidarity lines. Agriculture and food are considered to be strategic to build an alternative to austerity. Through these distributions, activists aim to give hope against despair, and to build collective bonds against increasing neoliberal individualization. These actions try to politicize and empower citizens for mobilizing against austerity policies.

These distributions thus are an integral part of the broader political movement directly confronting austerity governments and policies, while struggling for an economic alternative based on solidarity relations that implies a different state. This is done also by demanding policy reforms that confront the economic and institutional barriers for these initiatives to develop, and push for deeper changes in the agrifood system.

Via Campesina banner. Source: http://viacampesina.org

Conclusive notes

Tackling agrifood injustices and reclaiming real democracy involves challenging the political and economic powers that are structuring agrifood systems. Practical alternatives may contribute to open imaginaries and politicize agrifood issues, but without a more confrontational politics they can easily be a complement of or be assimilated by market forces. This implies engaging with a politics that does not refuses to tackle the state, but that, at the same time, goes further than policy reforms to embody an ambition to transform the state itself. Both cases show how activist strategies on the ground are tackling these issues, emphasizing the importance of developing practical alternatives in building a confrontational politics.

*This post is part of a series sharing chapters from the edited volume Political Ecology for Civil Society. Rita Calvário’s contribution with the original title ‘Reclaiming democracy through alternative economies activism: lessons from agrifood movements in the Basque Country and Greece” is included in the chapter on democracy. We are eager to receive comments from readers and especially from activists and civil actors themselves, on how this work could be improved, both in terms of useful content, richness of examples, format, presentation and overall accessibility.