After almost eight decades the story of the collectivisation of Aigües de Barcelona during the time of the Spanish Civil War emerges as highly insightful given today’s context of European crisis and the parallel worldwide trend towards re-municipalisation of water management. *

The changes that Barcelona’s Avinguda Diagonal underwent since it was renamed and lost its former name Avenida del Generalísimo – previously used during the Spanish dictatorship (1939 – 1975) – also include the gradual removal of several Francoist monuments. The stele honouring the Nazi Condor Legion was removed from public display in 1980. The Monumento a los Caídos (Monument to the Fallen) which was centrally located on the University campus was dismantled in 2005. And finally la Victoria, a statue by Frederic Marès commemorating the triumph of the Francoist army during the Spanish Civil War, was removed in 2011. Together these monuments once signified a grand Francoist memorial. Yet one monumental building built in 1939 to honour Barcelona’s occupying military forces remains in use today – as a residence for military officials. Its history is intimately linked to the collectivisation of the water company Societat General d’Aigües de Barcelona (SGAB) during the Spanish Civil War.

Reforms during the War

Just a few months after the beginning of the war, in September 1936, the banker and businessman Josep Garí Gimeno fled Republican Spain and sought refuge in Burgos, the territory of the revolting Spanish military. Garí was the man at the forefront of Banca Arnús-Garí and CEO of Barcelona’s private water company (SGAB). He promised the military generals running the revolt against the Spanish Republic that once that war would be over, SGAB would reward them with a donation of one million pesetas. In addition to this, two years later he would also provide a piece of land which he owned on Avinguda Diagonal.

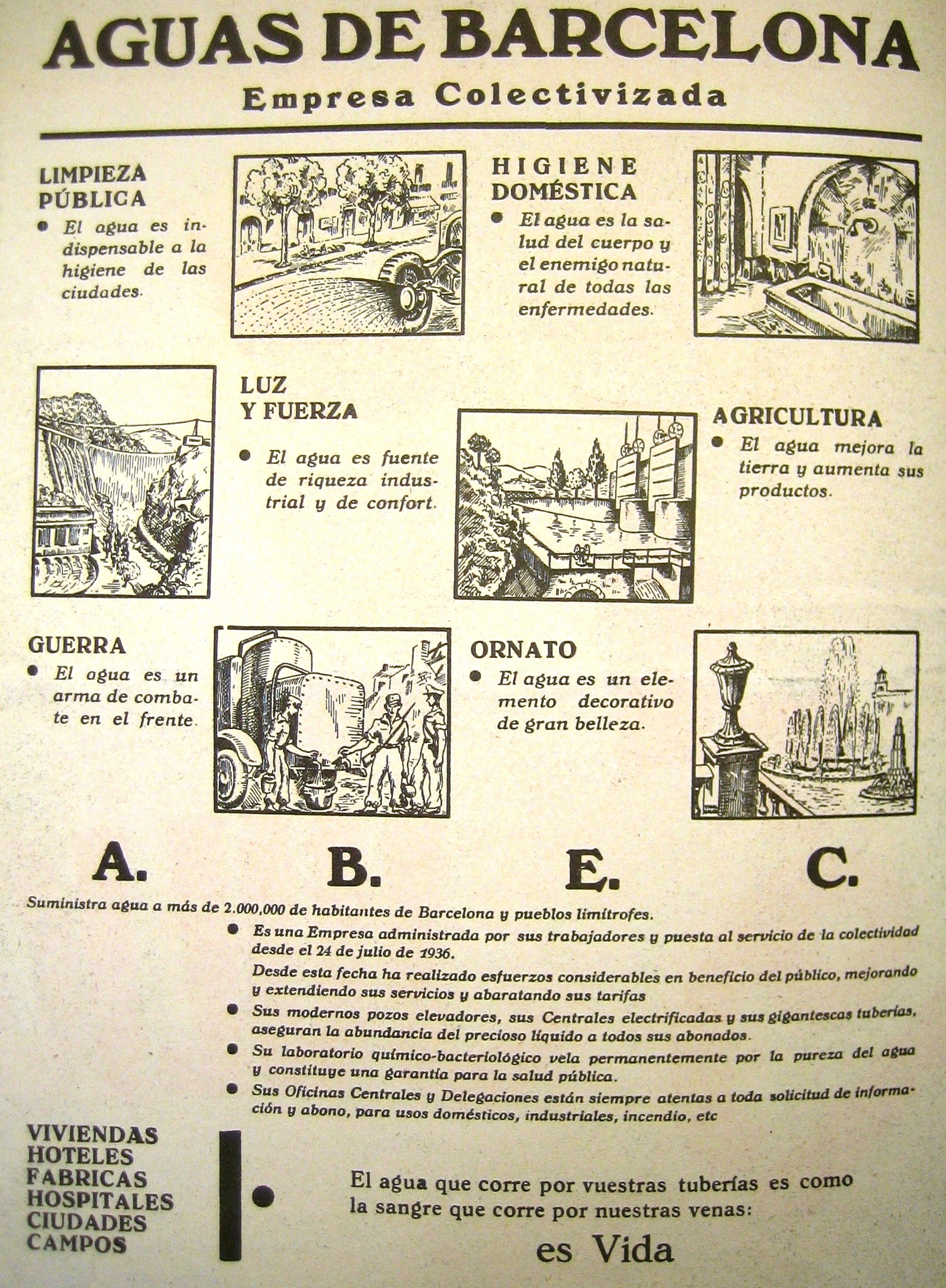

In the meantime, in Barcelona the water company was seized by its own workers, who had massively joined the ranks of anarcho-syndicalist union Confederació Nacional del Treball (CNT). Soon after, they put several reforms into practice: workers organised into assemblies in which they elected their own section and building committees, the working week was reduced to 36 hours while the total workforce of the company increased, and the house of the company’s director and the surrounding park were transformed into a school for the workers’ children, renaming it after Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia. A legal process was initiated and completed in 1937, fully collectivising the private company and giving it the new name Aigües de Barcelona Empresa Col·lectivitzada (ABEC).

These reforms also affected the city’s water supply. During the years of the Second Spanish Republic (1931 – 1936), the rent strike was one of the main social conflicts as water and power cuts were often used as pressure measures to enforce evictions of unwanted tenants. Water was often paid for by tenants as a fixed amount included in the rent, limited by a deposit, and sanitary conditions of the buildings were generally poor. Under the new collectivised management, landlords were suddenly forced to comply with municipal public health regulations and had to pay a fixed fee that would guarantee tenants a basic minimum of water consumption. Tenants would pay any excess consumption. Importantly, all perpetuity contracts that were often enjoyed by landlords of houses established in the late 19th century were terminated. While such measures cut into the landlords’ privileges, this improved the efficiency of the collectivised company which previously obtained no incomes from the water consumed under the old contracts.

Finally, the water price was standardised all over the city. This represented a significant price reduction in several neighbourhoods of Barcelona. But during the first months of the war and the revolution, many neighbours simply stopped paying their rent and water bills. In an interview with the newspaper Solidaridad Obrera, ABEC workers therefore demanded that the public pay their water bills and reminded that benefits would now improve public service rather than go into the pockets of former private owners.

Controlling Pollution

ABEC also tried to address a problem that 75 years later continues to hinder water supply in Barcelona. Today, as in 1936, the river Llobregat receives a significant amount of saline residues due to potash mining from the upriver Bages region. As a result of the mining operations which began there in 1920s, the salinity of water pumped into Barcelona slowly increased over time. Since 1932 a project had been on the table to build a channel which would divert the brines produced in the mining region into the sea instead. Collaborating with the Catalan Government, ABEC supported the further design of this project and completed this with the company’s own funding. The actual work to build the channel, however, did not begin.

Despite the war, ABEC guaranteed quality controls of the river, which had been established in 1932 and monitored the water salinity from the mining region. When the mines of Cardona, Súria and Sallent had to halt their operations due to the war, salinity in Barcelona waters began to decrease. By the end of the war, the control station managed by ABEC was the only one operating and salinity values registered there were similar to those from the beginning of upriver mining activities. Until then, the mine operators had always argued that water salinity of the region was a natural phenomenon. Once the war was over and mining resumed, the salinity levels increased once again. But the brine channel was not built until the end of the 1980s.

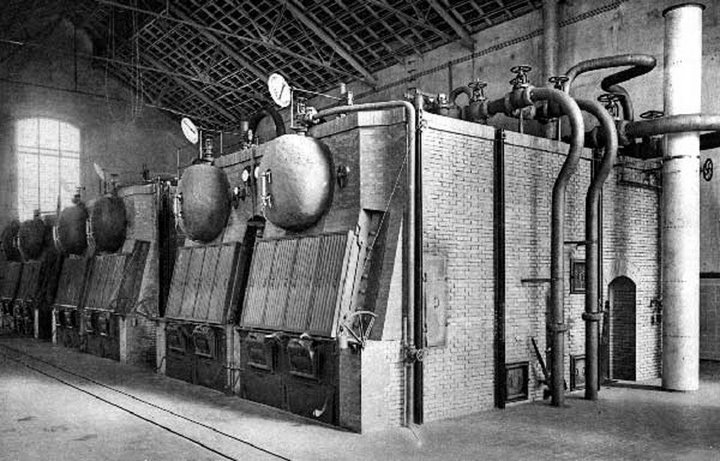

Starting in 1937 but especially during 1938, Fascist air raids in Barcelona put the collectivised management to test. Francoist occupation of the Pyrenean water reservoirs, producing most of the electricity consumed in Barcelona, forced ABEC to revert to the old steam engines to pump water in the city. Expenditure in coal increased and so did water prices. In 1938 an emergency decree had to be issued to prohibit water use in swimming pools and gardens. Additionally, the many urban gardens which appeared all over the city during the war also affected water supply because they often obtained water illegally from the company’s network. Despite such difficulties, the collectivised company managed to maintain water supply during the air raids. In fact, during the war water consumption actually increased significantly and ABEC also spent substantial amounts of resources in air raid shelters such as the one conserved under its former central offices (which today houses the Home Affairs Department of the Catalan Government).

The Return to Private Management

After Barcelona was occupied by Franco’s troops, the company’s previous private owners quickly regained charge of the water company and they were surprised to find it in good condition. As Garí had promised, SGAB soon paid a reward to the military and Franco decided that the donations should be used to build a residence for military officers. The laying of the foundation stone took place during the summer of 1939, close to the women’s prison of Les Corts. The donation lead by Garí and SGAB was financially supported by a further 70 companies and particulars (as presented on the back page of Nueva España in October 1940).

Given today’s European crisis context as well as the worldwide trend towards re-municipalisation of water management, after almost eight decades the experience of the collectivisation of Aigües de Barcelona emerges as relevant for at least three reasons: First, it shows the compatibility between a service based on the ideal of social justice and a management in a moment of crisis that emphasises the importance of efficiency. Second, the workers’ effort to continue with the environmental and sanitary control of the Llobregat waters has left us valuable information about the evolution of its salinity levels – something significant considering the present environmental conflict over potash mining in Bages remains alive some 75 years after the end of the war. Finally, the rent strike struggles are central to understand the context of some of the reforms carried out by ABEC. These show the enormous importance of water and energy as inseparable elements for every household. This is something the activism against energetic poverty continues to defend today.

* This piece was originally published in La Directa, nº375, in Catalan. For references and more information on the collectivisation of water in Barcelona, check out the following articles by Santiago Gorostiza.

Gorostiza, S., March, H. and Sauri, D. (2013), Servicing Customers in Revolutionary Times: The Experience of the Collectivized Barcelona Water Company during the Spanish Civil War. Antipode, 45: 908–925.

Gorostiza, Santiago (2013), “Diagonal 666. Un monument a l’ocupació de l’exèrcit franquista“, L’Avenç, 389, 42-50.

Gorostiza, S.; Honey-Rosés, J. and Lloret, R. In prep.: Rius de Sal. Una visió històrica de la salinització dels rius Llobregat i Cardener durant el segle XX. Edicions del Llobregat.

2 Comments