Through the analysis-using several ethnographic methods- of conflicts around ‘swiftlet farming’ in George Town, Malaysia, Creighton Connolly encourages the formation of stronger linkages between academics, urban policy makers, and civil society organisations for better understanding environmental conflicts.*

Edible-nest swiftlets are a small species of bird (Aerodramus fuciphagus), native to Southeast Asia, which make edible nests entirely of their saliva.‘Swiftlet farming’ is a colloquial term which refers to the cultivation of edible birds nests through preparation of specially designed buildings for swiftlets to roost and nest. Birds nests are a Chinese delicacy which are believed to have a number of medicinal, therapeutic and pharmaceutical qualities, and consequently command upwards of US$2,000 on the international market.

My research focuses specifically on the case of George Town, Penang, Malaysia, which has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2008. Due to the international prestige and economic importance attached to this status, swiftlet farming was declared illegal in George Town in 2009, and the government has since then (unsuccessfully) attempted to clear all swiftlet farms from the heritage zone. However, many Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) have criticized the lack of action by the state government in controlling this industry which, they argue, threatens both the (in)tangible heritage of the city and the health and safety of residents.

The tensions and controversies surrounding edible bird’s nest harvesting in Malaysian cities is a clear example demonstrating the importance of engaging a wide range of stakeholders in responding to environmental conflicts (see also, Affolderbach, Clapp & Hayter, 2012). Within the ongoing struggles over swiftlet farming in Malaysia, there has been a fundamental clash over the competing urban, economic and ecological imperatives at stake. This post draws on action research conducted in George Town in early 2014 to reflect on research methods that can be used to understand the variety of issues in environmental conflicts. Moreover, in recognising the social character of knowledge (Owens, 2011), this blog post encourages the formation of stronger linkages between academics, urban policy makers, and civil society organisations in order to achieve these goals.

‘Co-production’ is the term increasingly used to describe these new forms of encounters and engagements, and is increasingly shaping research agendas, institutional practices, and forms of governance (Polk, 2015). This piece will introduce three specific methodological tools that might be used by researchers and CSOs to work together on confronting socio-ecological conflicts. Specifically, this chapter explores narrative and discourse analysis, participatory action research, and conflict mapping in order to demonstrate how action-oriented research can utilise ethnographic methods to both answer research questions and achieve activist goals.

Figure 1: Location of George Town within Peninsular Malaysia. Source: author.

Narrative and discourse analysis

Narrative analysis involves the collection and examination of documentary or oral sources of information, which can be used to the study of any kind of discourse, from printed word to in-person interviews (Wiles et al., 2005). These include emails, letters, reports and presentations, individual and focus group interviews, as well as newspaper clippings, online articles and blogs. Such documents can help to identify the key actors involved, allowing further consultation with them during the research. Moreover, they make it possible to trace the webs of connections between the various actors involved in the conflict, and the various hierarchies at play. Official documents, such as government reports, industry guidelines and press releases can also be instrumental in identifying the diverse issues at stake.

In examining the controversies over swiftlet farming in George Town, newspaper articles were particularly useful in that they allowed for the identification of key narratives circulating within Malaysia regarding swiftlet farms. In the 100 plus articles collected, dating back to the early 2000s, there was a diversity of sides represented, including that of swiftlet farmers themselves, the government’s perspectives, CSOs like the Penang Heritage Trust (PHT) and Sahabat Alam (Friends of the Earth, Malaysia) and of course residents affected by swiftlet farms. By piecing together the various stories in the articles, the key moments of conflict and contestation between these different groups began to emerge, which allowed the construction of an overarching narrative of the key tensions over time.

However, there are some limitations with using a pure narrative or discourse analysis strategy for researching environmental conflicts. For instance, most newspapers or other document-based sources do not cover the full range of voices or information that one may need in researching a particular case. Therefore, it is important to be cognizant of such limitations when using narrative studies, so that the missing information can be collected via alternative means, as will be discussed below.

‘Participant observation’: Co-producing knowledge and resistance between researchers and CSOs

A third method used in the course of this research centred around a three month internship period undertaken with the PHT during February – May, 2014. This is a form of ‘participant observation’ in which the researcher actively works with those whom (s)he is studying (Buscher, 2006). Collaborating in this way allowed me for the daily contact and knowledge of CSO members and the opportunity to coordinate joint action against detrimental socio-environmental practices. Moreover, the interests of the CSO members were able to guide data collection and research outputs to a considerable extent.

One of the primary activities undertaken was lobbying government officials and UNESCO representatives with regards to their position on swiftlet farming in George Town. Since this type of work is an integral part of most CSO work, it will not be greatly elaborated on here, however, key points from this case merit brief consideration. First, the fact of being an ‘outsider’ in Penang, as both a foreign national and non-resident, allowed for a different type of interaction than the PHT council members had achieved in the past. Second, the key to working with the local authorities required pitching the research in a way that would also be useful to them. For instance, some municipal officers admitted (mistakenly) to perceiving me as an ‘expert’ in managing swiftlet farms in urban areas, and that facilitated knowledge transfer between the CSO members and government officials so that they could improve enforcement practices.

Conflict mapping

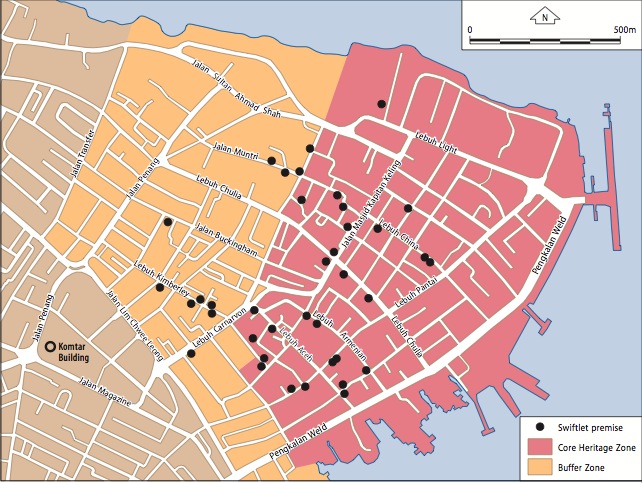

A final component of this research involved surveying the heritage zone (1.6km2 in area) for active swiftlet farms. In order to do this, I consulted previous records of active swiftlet farms in the inner city, which had been conducted in 2008 and 2011 by individuals from the PHT, University Sains Malaysia (USM), and the Penang municipal council (MBPP – Majlis Bandaraya Pulau Pinang). All counts were conducted manually, and locations were recorded on a base map of the city, as well as on a spreadsheet to record details and observations about each site. The revised count proved that despite the State Government’s announcement that they had been successful in clearing all remaining active swiftlet houses from the World Heritage Site by the end of 2013, this was not necessary the case. In 2011 there were estimated to be around 174 active swiftlet houses within the heritage zone, but as of May 2014, there are still at least 42.

Figure 2: Locations of active swiftlet farms in George Town’s World Heritage Site as of May, 2014. Source: author.

The resulting map of active swiftlet farms (see fig. 2) was useful in several ways. First, and most importantly, it was used to put additional pressure on the state government to fulfil their promise of removing all illegal swiftlet houses from the heritage zone by the end of 2013. Updating the numbers and locations of swift houses also added important data to the existing CSO records regarding the numbers of swiftlet farms in the city, which allowed for the identification of patterns over time and clustering of swiftlet farms in certain areas.

Conclusion

This post has intended to shed some light on how researchers and CSOs can work together in co-producing knowledge on and resistance to environmental conflicts. The methods and tools discussed in this section have been used to understand the causes of environmental conflicts and how different stakeholders make both sense of and represent the issues at stake. This post has also demonstrated the importance of democratic participation in the resolution of environmental conflicts, as their causes and thus solutions necessarily requires the cooperation of NGOs, industrial alliances, different levels of government and other actors with competing interests (see also Affolderbach et al, 2012).

The collaboration among research and CSOs members for this research involved not only sharing co-produced information with relevant authorities in a constructive manner to aid their enforcement work, but also engaging with government officials to understand and overcome the challenges that they faced in doing so. Although the conflict was not fully resolved, the additional pressure put on the state government to uphold their promises did result in an improvement of the situation. In sum, this post stresses the necessity of making deep connections between academics, CSOs and other stakeholders, in order to tackle complex environmental conflicts such as the case presented here.

* This is the first post in the series sharing chapters from the edited volume Political Ecology for Civil Society. Creighton Connolly’s contribution ‘Co-producing political responses to ‘swiftlet farming’ in George Town, Malaysia’, is included in the chapter on environmental conflicts. We are eager to receive comments from readers and especially from activists and civil actors themselves, on how this work could be improved, both in terms of useful content, richness of examples, format, presentation and overall accessibility.