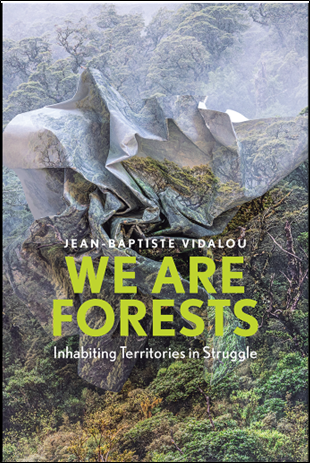

Alexander Dunlap reviews and discusses Jean-Baptiste Vidalou’s We Are Forests: Inhabiting Territories in Struggle.

by Alexander Dunlap

It’s shameful. The original French publication of We are Forests: Inhabiting Territories in Struggle by Jean-Baptiste Vidalou was in my hands since April 2018. Frequently described as “the French Seeing Like a State,” the book explores the art of state making in France. Having been in stimulating dialogues with Jean-Baptiste Vidalou (JBV) since 2018, and being linguistically challenged, I knew the general ideas and points in the book—but never fully read it! Now, since September 2023, the book has been published in English. And, as of today, I have finally read the book front-to-back and, for this delay, I apologize JBV.

Why apologize? Well, the book—considering my interests and standards—is f#%king amazing. While partially insulted I was not asked to do a testimonial for the English version of the book, I use this to pretend we are even for my abhorrent review delay. Described as “a dry-stone wall builder and philosopher” on the back cover, Vidalou presents us with a book packed with crucial, some might call, “insurrectionary research” and an expose of “anarchist political ecology” into state making in France—even if the author would likely not define themselves this way (or at all). Reading the book provides cathartic joy, combative insights and poetic wit, which deserves acknowledgement and discussion before it completely falls into the void of academic publishing.

Into the Forest: The Strife that is Existence

Written in a pithy, sharp and fluid style, the book has nineteen chapters and takes us from ancient times to 2016, while occasionally taking the reader to other parts of the world outside France. We are Forests weaves together state formation, the central role of technical expertise, counterinsurgency strategies and how they separate people from forests and our wider communities. “Preservation and exploitation are today the two sides of the same colonization,” explains Vidalou, continuing that “what is known as ‘territorial management’ must be understood as a low-intensity war” (p. 7. emphasis added). The book is about social war and colonization, revealing the intimate disciplining, control and warfare waged against forests and people alike to meet the imperatives of state and capital.

This book, as the title suggests, is also about inhabiting territories—being intrinsically connected to habitats—and charting how that relationship is destroyed and how resistance revives it. We are Forests, in terms of political ecology jargon, is an expose into “political forests” occupied by France (Peluso & Vandergeest, 2011), documenting the intimate relationship between insurgent resistance and forests. The first half of the book, while interweaving contemporary references to the NoTAV and ZAD struggles, is dedicated to analyzing the Camisard’s war at the turn of the 17th Century and the process of subjugating and colonizing the mountainous south-central region Cévennes into the present. “The Camisard’s war,” Vidalou reminds us, is a “textbook case studied by experts in counter-insurgency strategy so that “military lessons can be drawn from the mountains of the Cévennes for the efforts in Afghanistan” (p. 14). Revealing the complicity of engineers, planners and infrastructure in military operations, JBV, summarizes:

Cartography, from its imperial origins, was conceived as a tool of colonization, a way of writing the story of a conquest in which the civilized takes over territories that are supposedly “empty” but which in fact always have to be “emptied” because they are populated. The others, the remote, exist only to be denigrated, domesticated, erased.

Colonization throughout the book, refers to the subjugation of people, breaking them to the whims of an invading centralized authority, its economy and dominating culture, whether in the area demarcated as France or overseas. We are Forests reveals the intensity of struggle, war and territorial management that took place within France, often overshadowed by the later, or simultaneous, brutality of colonial warfare overseas. The book demonstrates these brutal origins within France before and during the French colonialism.

Dwelling on the technics of pacification, a central theme within the book is the role cartographers, planners and engineers play within formal and informal military campaigns to domesticate landscapes and people. Vidalou locates these roots with mechanical philosophy, Henri de Saint-Simon and the Physiocrats obsession with counting, measuring, disciplining and exerting geographic control over forests and people. “These accounts of surface area and volume, these comparisons of habitation, these inventories of resources,” Vidalou contends, “are part of a totalising ideology that subjects all things to the accounting imperative” (p. 61). This leads the author to exclaim that “reducing the world to book-keeping” is a “Western disease” (p. 64). Carrying forward the critiques of Jacques Ellul, Paul Virlio and Micheal Foucault, Vidalou remains profoundly concerned with how state and technological domination is rendered legitimate and normal through administrative procedures and science. Modernist infrastructures, planning procedures and engineering, we are told repeatedly, “arranges spaces, it administers things, it governs people” (p. 8). “[D]ata calculations,” for Vidalou, “end up replacing reality; they become reality itself” (p. 61).

The book’s critique, eventually leads to green economy. “When managers speak of ‘eco-systems’, ‘biospheres’, ‘thermodynamic machines’, ‘Earth systems’, what language are they speaking?” Asks Vidalou (p. 153). The further commodification of habitats, but also the spread of new so-called ‘green’ projects is identified within the book as absurd.. The book debunks ideas of energy transition, revealing that they are “additions” and still enact Walter Rostow’s “Stages of Economic Growth.” “There is no energy transition, there is only the same logic everywhere in charge: extract, extract, extract,” Vidalou exclaims, “France has never burned as much coal to produce electricity as it does today, when its consumption is skyrocketing” (149). The green economy is exposed as a farce, which is “above all” designed for “saving the economy” and not habitats or people (p. 153). Energy transition proposals, says Vidalou, “are in fact a further step towards governing the whole world” (p. 172). This green capitalist expansionism and political control, Vidalou shows, relates to cybernetics, which is designed “to model, anticipate and affect possible behavior in advance” (p. 167).

We are Forests stresses the necessity to reweave and acknowledge our intimate connections with our habitats. Attacks against forests, rivers and trees, we are reminded, are attacks against us, other inhabitants, surrounding bioregions and even, with accumulating degradations, the planet. Relating to territorial struggles around Europe, the book indicates the profound “political ontology conflicts” taking place. “Ultimately, it is a war between two rival perceptions of the world,” explains Vidalou, “A war between those who, with their abstracted point of view, claim to reduce reality to economics, and those who, on the basis of sensual perceptions, start from where they live and try to link themselves to the reality that runs through them” (p. 179). Traveling from French state formation, military strategy and ‘green’ projects, such as ‘smart’ technologies and wind extraction enclosures, elevated to the level of ‘public utility,’ the book’s main point is to remind us that “territorial management” is intimately related to warfare and civil domestication and that, if we are resisting it, then “We are the forest defending itself” (p.183).

We are Forests stresses the necessity to reweave and acknowledge our intimate connections with our habitats. Attacks against forests, rivers and trees, we are reminded, are attacks against us, other inhabitants, surrounding bioregions and even, with accumulating degradations, the planet. Relating to territorial struggles around Europe, the book indicates the profound “political ontology conflicts” taking place. “Ultimately, it is a war between two rival perceptions of the world,” explains Vidalou, “A war between those who, with their abstracted point of view, claim to reduce reality to economics, and those who, on the basis of sensual perceptions, start from where they live and try to link themselves to the reality that runs through them” (p. 179). Traveling from French state formation, military strategy and ‘green’ projects, such as ‘smart’ technologies and wind extraction enclosures, elevated to the level of ‘public utility,’ the book’s main point is to remind us that “territorial management” is intimately related to warfare and civil domestication and that, if we are resisting it, then “We are the forest defending itself” (p.183).

We are Nature Defending Ourselves

If they were alive, I imagine Paul Virilio would enjoy and take inspiration from this book. We Are Forests, continues the Virilian tradition revealing subjugated histories, centering popular ecological struggles and deconstructing the green economy as a market-oriented warfare strategy. The decolonial debates, especially as they are influenced by European International Courts, tend to overlook the mechanics, organization and technologies of colonialism in favor of identity and geopolitics. While this decolonial approach offers important insights, it forgets the roots of colonialism in civilizations, empires and states. To become a colonial power, Vidalou reminds us, they first had to discipline, domesticate and destroy the peoples—water, trees, mountains, humans and their cultures—before imperial and state power could be formed to go commit overseas atrocities and establish political systems of plunder (e.g. extractivism). Becoming accustomed to the colonial political model—its socio/ecological separations, hierarchies, etiquette and its bureaucratic enclosures by steel, copper, asphalt, concreate and computational systems—has a way of making people forget themselves within the competitive enchantments of modernity. We are Forests highlights the colonial roots, technologies of pacification and, most of all, a common war, or low-intensity war, that people face under different histories, political circumstances and possibilities.

This low-intensity war, Vidalou shows us, is extended by the green economy. A theme understood by eco-anarchists, We are Forests was among the first to acknowledge these implications in the matter of wind turbines and lower-carbon infrastructural systems. Vidalou discusses the destruction, augmentation and loss brought by lower-carbon infrastructures, but also the political consequences of these seemingly ‘green,’ ‘clean’ and ‘renewable’ technologies. Lower-carbon technologies “are not intended to escape from this moribund system, but to legitimize it in its entirety,” explains Vidalou, “They do not seek more viable trajectories for this world, but just to stay on the rails of progress.”

Documenting the destructive effects of so-called green energy technologies on habitats, Vidalou charts the socioecological and political implications of so-called energy transition that most missed and still struggle to understand. We are Forests identifies a crisis of socioecological separation, ignorance of subsistence within habitats and how the qualitative dimensions are being erased by the state, economy and the science that reinforces them. All of this, makes this book highly recommended for everyone concerned for forests, our survival and resistance. We Are Forests is a critical breath of fresh air that came late to the Anglophone world.