By Anne Degenhardt, Batsaikhan Abdul Mohseen Yahya and Beulah Seema Soans

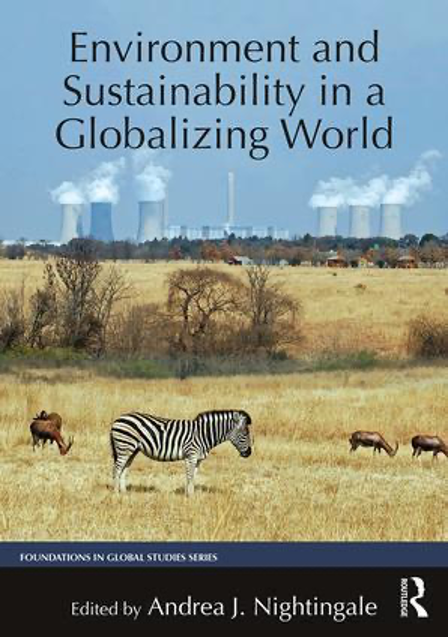

A students’ review of Andrea Nightingale’s book “Environment and sustainability in a globalizing world”.

Back in 2019, at the beginning of the winter semester, we were sitting in a blank white classroom at the University of Passau, in Germany, waiting for Dr. Martina Padmanabhan to start a MSc course titled “Sustainability”. Looking at each other’s confused faces, we silently understood that only a few of us had any experience in this field. Of course, we had heard the term before, but we simply and broadly related it to ‘the environment’. We didn’t yet know how many facets the study of “sustainability” could reveal to us. We were a class of master students from different ethnicities, cultures and with different backgrounds: business, economy, history, culture studies.

The book Environment and Sustainability in a Globalizing World is edited and co-written by Andrea Nightingale –a well-known scholar in the political ecology field, who currently teaches at the University of Oslo. The book became the key text of our course and this blog sprouted from the process of learning and discussing on the topic of sustainability in class, and from the interlaced creativity between the students and the teacher. We here then attempt to review this book collectively, as an interdisciplinary group of students who do not have much experience in the field. Yet, we think our modest reflections could inspire some readers to become more curious about the multi-layered concept of sustainability.

The book is divided into two parts, the first dealing with basic theoretical ideas around the concepts of sustainability and sustainable development, and the second presenting different cases to illustrate some of the many different ways to understand, measure, quantify and experience sustainability.

Theoretical approaches to sustainability

The first part of the book consists of six chapters covering, among others, the themes of: the history behind the coinage of the word ‘sustainability’; the different narratives around sustainability by various groups and entities such as indigenous people, private companies, or NGOs; the enactment and institutionalization of sustainability; and the issues and challenges of scaling and measuring sustainability. Every chapter consists of rich, up-to-date information from numerous sources, illustrated in a way that the reader would feel motivated to immediately follow the citations.

In other words, the first chapters are an excellent entry point into the world of sustainability, helping a “newcomer” to find their way. We learned more about methods to measure “sustainability” as well as about the human rights struggles of indigenous people and how these relate to “sustainability”. In this regard, every theoretical idea is explained very graphically and through the use of specific examples, allowing the reader to bridge theory with real life.

For example, the authors explore the entanglements of nature and society, through the concept of “socionature”, suggesting it as a core concept for understanding sustainability and the narratives around it. In fact, changes in the natural/environmental/biophysical dimensions are juxtaposed with changes in the social/political/cultural ones. Nightingale and co-authors illustrate various examples of what this fluctuant and adapting relationship entails, guiding the reader to understand its complexity.

Nevertheless, the concept of socionature only relates to one narrative of sustainability, referring to the inevitable connection between human and non-human dimensions. There exist different approaches to tackle the question of whether, to what extent, and how environmental issues relate to social ones. In this regard, we critically reflected on two main points in our class. First, on the importance of distinguishing between epistemology -or how we can know nature–society through representations- and ontology -or how we assume nature–society are linked- (see Nightingale 2019: 37), when unfolding different, situated understandings of the relationship between nature and society, and thus also of sustainability. These concepts of epistemology and ontology form the basis for all sustainable approaches -such as socionatures, anthropocentrism or ecocentrism- discussed in the book and in class, since they explain the links between society and nature and therefore give us the necessary knowledge to understand each of them better.

Second, we reflected what anthropocentrism and ecocentrism mean, to re-think the value of different species in the world. We found particularly interesting the concept of ecocentrism, which is a philosophy that sees human and non-human nature are equally important in the world; meaning, humans should not consider themselves as of superior value compared to non-human natures. Some of us agreed that ecocentrism should be a starting point to approach sustainability issues, for human and non-human nature holds -ontologically- the same value. Others preferred an epistemological approach, arguing for the importance of focusing on relationships and interdependencies between different species, human and non-human nature, in order to tackle sustainability issues. This discussion intrigued and inspired us to look for more information about different theoretical approaches inside the multifarious field of sustainability.

Source: colorbox

Case Studies: Contextualising the struggle over sustainability of what and for whom

The second part of the book presents a wide range of ethnographic case studies, which are meant to help readers “see the theory in action”. The case studies illustrate the role of sustainability in relation to, among other themes, alternative food movements, community forestry, sustainable mining, genetically modified crops, gender equality. Hereafter we present some of the cases we liked most.

Sustainable mining

The case study presented in Chapter 10 was written by Nancy Langston, an American environmental historian, and described the “war” between local communities against mining projects and the corporate extractive companies supporting those projects . Through empirical case studies, the author shows how different stakeholders -mining companies, environmentalists, local community representors- have different perspectives about sustainability and/or sustainable development. While mining companies boldly defend their actions by insisting on their economic benefit (taxes, royalties and job opportunities); local communities may be against mining projects because these may have disastrous consequences on the nature they inhabit and are part of. Often an enormous work of mediation and negotiation is necessary in order for mining companies and local citizens to compromise their interests. Through this case, we as students clearly perceived the difficulties of maintaining a balance between economic growth and nature preservation. During our discussion about whether something like sustainable mining is possible, some of us agreed that strict regulations are necessary, while others thought mining should be completely banned.

Governance perspective on contested GMOs

Chapter 11 is written by Philip Macnaghten (University of Wageningen) and is about governing agricultural sustainability and genetically modified crops (GM). The DNA of GM crops has been modified through genetic engineering methods (for further insights into the current debates on GM, see the blog entry “ by Jose Luis Vivero Pol). The chapter starts with a review of the debates around agricultural sustainability. The author compares the struggles over GM crops in India, Brazil and Mexico. What we found most interesting is how the author emphasizes the importance of a framework for responsible innovation, focusing on anticipation, inclusion, reflexivity and responsiveness in the governance of new technologies. Again, we distinguished different positions and opinions around GM crops related to their justification (or non-justification) from different perspectives and ideologies. This case demonstrates how agricultural sustainability can be tackled from various angles.

Critique: Weaving of concepts and cases

Environment and Sustainability in a Globalizing World is a great choice for those with little or knowledge of what sustainability means. Yet, the connections between some of the theoretical concepts presented and the case studies remained to us a bit unclear or missing.

For instance, in the second part of the book – the case studies- , the reader seldom encounters theoretical concepts such as that of “socionatures”, described in the first part. While every chapter introduces a new environmental challenge, providing different perspectives on the challenge and illustrating several case studies to demonstrate how the challenge was dealt with in different ways, we struggled to see how to analyse or frame these environmental issues under specific theoretical concepts.

At the same time, the book made us very curious and inspired us to conduct more research on sustainability. We found it extremely rich in terms and concepts related to sustainability, which inspired us as much as it sometimes overwhelmed us, for we were often left with more questions than answers. Despite, or perhaps exactly because of this, we recommend the book to anyone interested in sustainability, independently of academic background or specific interest.

—–

Anne Degenhardt is a master student in Governance and Public Policy, Udval.

Udval Batsaikhan, Abdul Mohseen Yahya and Beulah Seema Soans are master students in Development Studies, all based at the Universität Passau, Germany.

References

Nightingale, Andrea J. (ed.) (2019): Environment and sustainability in a globalizing world, first edition, New York NY: Routledge, https://doi-org.docweb.rz.uni-passau.de:2443/10.4324/9781315714714.

Macnaghten, Phil (2019): Governing Genetically Modified Crops and Agricultural Sustainability in: Andrea J. Nightingale (ed.), Environment and sustainability in a globalizing world, New York NY: Routledge, S. 182-200, https://doi-org.docweb.rz.uni-passau.de:2443/10.4324/9781315714714.

One Comment