by Alexander Dunlap

Why do degrowth intellectuals publicly neglect combative self-defense against “growth” projects? The connection between degrowth and anti-capitalist, autonomist and (ecological) anarchist movements exists, and it can be strengthened by acknowledging the legitimacy of a diversity of tactics as necessary pathways towards degrowing the techno-capitalist system and protecting habitats form infrastructural invasion.

Degrowth is about reducing total material and energy throughput, which entails rejecting elite accumulation and the ideology of capitalism itself. For some—those acquiescing or clinging to the growth euphemism—degrowth is a provocative term. “Trying to avoid provocation, or trying to be agnostic about growth,” explains Jason Hickel referring to degrowth, “creates a milieu where problematic assumptions remain unidentified and unexamined in favour of polite conversation and agreement.” However, in matters of political struggle, it seems that the same applies to degrowth.

Currently, influential degrowth approaches veer towards polite political conversation, mainstream movement politics and largely ignore the combative struggles putting degrowth into practice closest to home. While ambiguity can create space, we ought to acknowledge—and support to various degrees—the full range of degrowth action. Specifically, the land defenders fighting economic growth and its interconnected infrastructural schemes.

This issue gained increasing relevance for me after designing a course on degrowth and following three months of connecting with people fighting energy infrastructure projects in France, Catalonia and Spain. Combative ecological struggles are important, yet the degrowth community tends towards ignoring or selectively mentioning antagonistic struggles enacting lived practices of degrowth. Struggles embodying “monkey wrenching,” “diversity of tactics” and articulating a “brisantic politics” are quite literally stopping—or attempting to stop—the expansion and/or growth of capitalist infrastructure into forests and ecosystems. Why do degrowth intellectuals publicly neglect these struggles?

The connection between degrowth and anti-capitalist, autonomist and (ecological) anarchist movements, as they converge to defend habitats, can be strengthened. The connection exists, yet remains vague in the popular degrowth literature. Inversely, when asked about “degrowth” in ecological struggles in France, Catalonia and Spain, land defenders see little relevance, associating degrowth with NGO politics, university culture and middle-class environmentalism.

One visible obstruction to this connection is degrowth’s ambiguity regarding “diversity of tactics” and combative direct action. In response, degrowth should embrace the “de” in “degrowth:” Recognizing the legitimacy in destruction or, more accurately, combative self-defense in struggles against “growth” projects and all that entails. This translates into degrowth intellectuals, teachers and organizers acknowledging these struggles vocally—including them into the degrowth lexicon—by recognizing their contributions to combating (capitalist) growth projects and defending habitats.

This short essay, in addition to highlighting this issue, further draws a link with degrowth and four socio-ecological struggles in Europe. Degrowth is vitally important, yet—following Hickel’s approach—the time has come for degrowth to become less polite and unambiguous about the importance of combative socio-ecological movements.

Recycling has many forms: A Hambach Forest barricade, 2015. Source: Wikicommons

Ignoring movements, sanitizing political struggle

The recent book Degrowth in Movement(s): Exploring Pathways of Transformation is a remarkable contribution, taking important steps to articulate the degrowth movement with different social movements and practices. While an important and recommended reading, the omissions are shocking. The book is commendable for linking various movements—urban gardening, food sovereignty, ecovillages, mass-movement and Do-It-Yourself (DIY) initiatives—yet it is haunted by ignoring what could be easily argued are the most important and committed “degrowth” movements in Europe.

The book neglects in full or in part so-called “militant” struggles to live communally and stop—through a diversity of tactics—capitalist infrastructural expansion. In the following, I will briefly highlight some of the omitted struggles that deserve celebration from the degrowth community, before discussing this blind spot.

Hambach Forest Occupation, Germany

Given the German-centric nature of Degrowth in Movement(s), it is surprising it does not speak of the Hambach forest occupation, even though it devotes attention to the weeklong annual Ende Gelände gatherings and civil disobedience actions that take place there. Still ongoing since more than ten-years, the Hambach forest occupation aims to protect the Hambach forest from the “migrating” and largest coal mine in Europe.

While the struggle has had ebbs and flows, it has mostly been a forest occupation, where people lived in tree houses to protect the forest. This minimalist life style, organized around donated caravans, tree houses and compost toilets, combined with systematic acts of sabotage and confrontation with the company and police. The movement survived numerous large-scale police operations, constant intimidation and experienced one death. Moreover, the Hambach struggle, because the mine is supported by wind and solar infrastructure, has retained a strong critique against the green economy and “renewable energy.” The Hambach forest occupation, and related actions, should be embraced and celebrated for exemplifying the “de” in degrowth.

The NoTAV Movement, Italy

The NoTAV movement stands for, No to the High Speed Train. The struggle is located in the Susa Valley, where construction of a high-speed railway in addition to existing railways between Turin and Lyon has been planned. Going on since the mid-1990s, the NoTAV movement is a mass movement with numerous protest sites (presidi) all over the Susa Valley that celebrate anti-capitalist communality. Moreover, it is a movement of direct action: mass-demonstrations, fending off police invasion, blocking and sabotaging construction sites.

The NoTAV resist the onslaught of the high-speed train, but also offer many alternatives to the further infrastructural colonization of the valley, embodying a degrowth vision of transportation: changing the production systems to decrease long distance transport of people and goods; supporting local sustainable trades instead of big industries; and improving local transport. The repression of the NoTAV movement has been severe, which only stresses the importance of the Degrowth network recognizing and supporting these struggles.

The ZAD (Zone-to-Defend) Movement, France

Beginning in Notre-Dames-Des-Landes (NDDL) to fight a new mega-airport outside Nantes, ZADs refer to inhabited areas designed to blockade forthcoming development projects. The acronym “ZAD” is a Situationist détournement, or subversion, of “deferred development area”—an area designating a megaproject—to a Zone to Defend (ZAD) from that development. Like the NoTAV movement and Hambach forest occupation, the ZAD movement articulates communal ways of living with their ecosystems and defend them against police-military and company incursions.

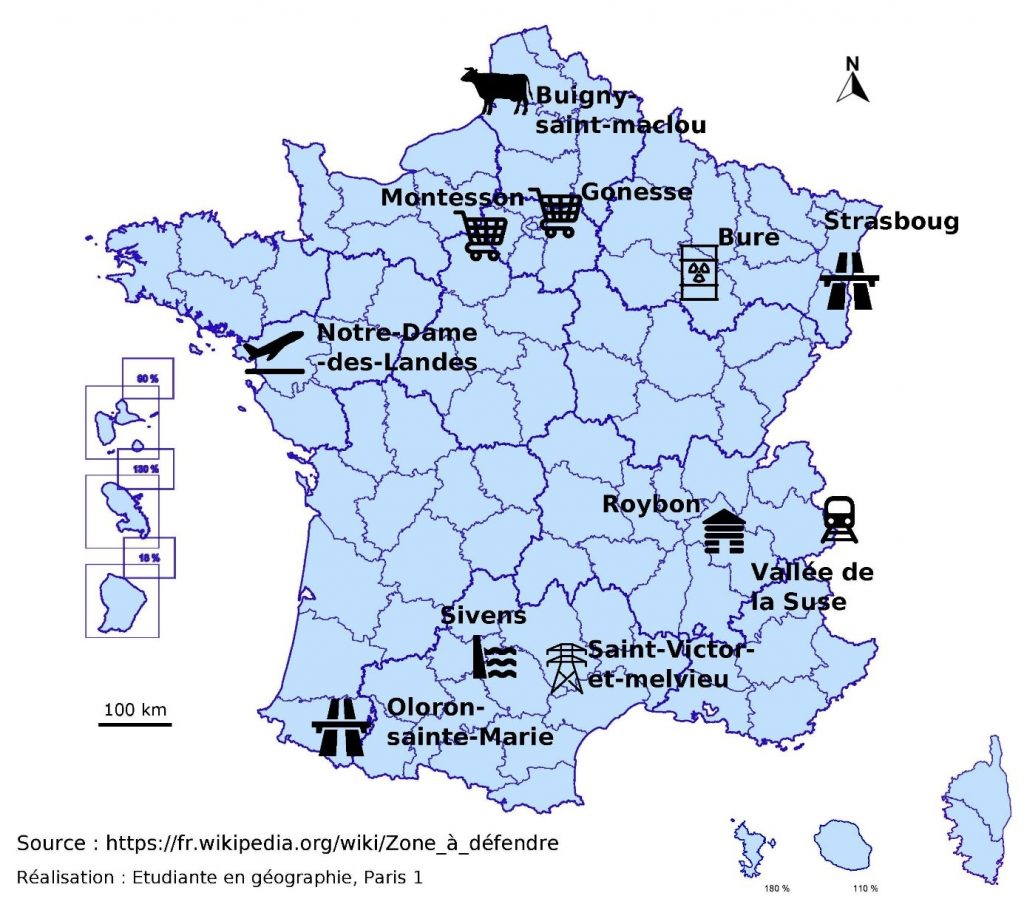

Despite internal turmoil, the NDDL ZAD eventually defeated the airport project in 2019 and, equally important, the ZAD concept has spread all over France as a way of living in permanent resistance against destructive growth-oriented development projects. In 2015, the newspaper Le Monde, contended that there were 27 ZADs. While one sentence references the NDDL ZAD in Degrowth in Movement(s), the numerous ZADs, their struggles and successes are sidelined in (Anglophone) degrowth literature.

The Anti-MAT Struggle, Catalonia

Beginning in Catalonia in 2004, the Anti-High-Tensions (Molt Alta Tensió, MAT) Power Line struggle seeks to resist the infrastructural colonization of their territory. This movement, like the others, is diverse, including various civil-society groups, supportive politicians and direct actions. Fighting the domination of Catalonia by Spanish energy monopolies and their infrastructure, numerous demonstrations took place over a span of 15 years, along with the Anti-MAT Forest Squat (2009-2010), civil disobedience and acts of sabotage (2010-present).

This struggle seeks to challenge the growth imperative of European energy markets whether with nuclear or “renewable energy” power plants in France, Spain and North Africa. Another struggle of significant importance to degrowth within its own backyard, yet with little to no mention.

A list of ZADs in France. Source: Wikipedia

Why ignore committed struggle?

The occupation and direct action movements are nearly endless. Remember the NoTAP (Trans Adriatic Pipeline) struggle, numerous ZADs, inhabited forests in Uppsala and forest defense against highways in Germany and so many more across Europe and the world. Considering the state of ecological and climate crisis, employing brisantic politics and “diversity of tactics”—“vandalism” (or art), sabotage, blockades or destruction of coercive infrastructure—is legitimate. This is real democratic participation in matters where people have no vote or choice, only consultation.

Degrowth celebrates mainstream environmentalism promoting climate marches, weeklong gatherings and civil disobedience actions. Yet, why ignore the decades long struggles committed to inherently enacting degrowth within Europe itself? This extends to other schools of thought and academic disciplines as well. Degrowth should embrace and celebrate combative movements, spreading the knowledge of their struggles.

Degrowth has, and should not deny its teeth

The connection between degrowth and direct action movements should be strengthened. Degrowth intellectuals should recognize combative socio-ecological struggles. Because, as Michael Truscello reminds us: “What we deter or destroy today will mean more to our collective future than anything we build or repair.” Ignoring these struggles or, worse, attempting to discursively manage them as “radical” or “militant”, reveals a colonial Stockholm syndrome, class-bias and institutionally supported narratives of the all too often “well-educated.” This plays into the notorious trap of the good/bad protest dichotomy.

These struggles, in reality, are not “radical” nor “militant:” they are logical pathways towards degrowing the techno-capitalist system, actions echoed by land defenders across the world to protect their habitats form infrastructural invasion. Degrowth advocates should acknowledge these struggles, recognizing the legitimacy of the diversity of tactics.

Finally, degrowth—and all academic schools of thought— must be careful not to tokenize struggles elsewhere across the world, meanwhile ignoring the permanent socio-ecological conflicts in their front yard. Degrowth intellectuals or organizers should not deny, nor isolate the movements on the frontlines. The opposite extreme, researching them by placing them into a Petri dish of analysis is also ill advised. Instead, spreading information, celebrating these actions and revealing the processes that impose megaprojects is another way to strengthen the connection between ecological anti-capitalist and degrowth movements.

Alexander Dunlap is a post-doctoral fellow at the Centre for Development and the Environment (SUM), University of Oslo. @DrX_ADunlap.

With the benefit of a few years behind me, I remember in London in the mid 1990s , some pretty furious and confrontational degrowth movements. George Monbiot and compatriots occupying the Brewery site in Wandsworth and establishing an eco-village. It lasted from May to October 1996. They were protecting it from development into luxury offices or flats, planting veg and living on site. There was definitely a degrowth feel when I visited with Phil Steinberg and there was certainly police confrontation. They same period saw the anti-roads protests – blocking the M4 for a few hours near Heathrow and ripping up tarmac and, from 1993 until 1995 , also opposing the M11 link road in Leyton in which communities established residence in the condemned houses as a ‘micro-nation’. The battle was about keeping the houses, but also opposing the capitalist expansion that the road represented in the still-poor East London. The last protester house was demolished in 1995 but sabotage of the road continued after that.

All of these movements were ultimately unsuccessful. All had anarchists, some had some pretty violent characters [Monbiot had some stories, one or two appeared in the Guardian columns] but those were the minority. Earth First! UK was involved with an anarchist environmental ethos. Many of the people participating in all of these will be in their 50s and 60s now. I wonder what they think about today’s struggles – XR, anti-fracking in Britain, etc.? The legacy of these early forays, and the EF movements in the US, are beginning to get a bit distant timewise and I wonder if there are direct historical links.