By Melissa García-Lamarca and Neil Gray

A massive regeneration of the post-industrial canal is prioritizing higher-income newcomers over the housing needs of long-term, low-income residents.

Editors’ note: This post forms part of the series “Green inequalities in the city”, developed in collaboration with the Green Inequalities blog of the Barcelona Lab for Urban Environmental Justice. The series seeks to highlight new research and reflections on the linkages between the dominant forms of “green” redevelopments taking place in cities and questions of urban environmental justice, and the challenges and possibilities these imply for more just and ecological urban spaces.

The Forth and Clyde Canal, built in 1790, traverses some of Glasgow’s most deprived areas in its course across Scotland. By the 1960s, new forms of mobility and transportation meant that the canal, historically used to ship industrial goods, was abandoned. Since the early 2000s, millions of funds have been allocated to its regeneration, transforming it into the climate-adapted Glasgow Glasgow Smart Canal with the aim of attracting house and pleasure boats, tourists and leisure-seekers. Yet as thousands of new homes are being built in the area in mixed income developments that will be 80% privately owned, the question is who will ultimately benefit from the new smart blue-green interventions.

View of the canal. Source: ReGlasgow.

North Glasgow “unlocked” for investment, regeneration and development

Smart Canal, green bridges, sustainability, massive regeneration. These are some words used to describe North Glasgow today. The interventions underway are an intensive attempt to reverse the neglect and decline the area has suffered over the past 50 years, including the depopulation by demolition of the Sighthill and Hamiltonhill housing estates. The government agency Scottish Canals underlines how the “pioneering new digital surface water drainage system” unlocks investment, regeneration and development opportunities across the area.

Despite its central location, Glasgow’s canal was physically and mentally severed from the city center by the massive M8 motorway built in the 1970s. A new pedestrian and cyclist street in the sky bridge planned to connect the canal to the city centre will breach this barrier to some extent. The green bridge forms part of the £250 million, 50-hectare Sighthill Transformational Regeneration Area, the biggest project of its kind in the UK outside London. Sighthill had become a highly stigmatized public housing estate. It was built in the 1960s and contained ten 20-storey towers lodging approximately 7,500 people.

Historically a heavy industrial site that was never properly decontaminated, Sighthill became a byword for deprivation in the 1980s due to purposeful under-maintenance and neglect, regional unemployment issues and resultant social issues. The towers have seen phased demolition over the past decade, despite considerable resistance from the Sighthill Save our Homes independent tenants’ group. Similar to the other seven city-wide Transformational Regeneration Areas identified by Glasgow City Council, the area is being redeveloped with public funding as mixed income housing. The dramatic privatizing tenor of this transformation is epitomized at Sighthill, with 2500 public homes being reduced to less than 800 homes, with only 140 for social rent and the rest private or mid-market rent.

Promise and reality: Glasgow canal at Speirs Wharf, with Cowcaddens housing estate in the background. Photo by Neil Gray

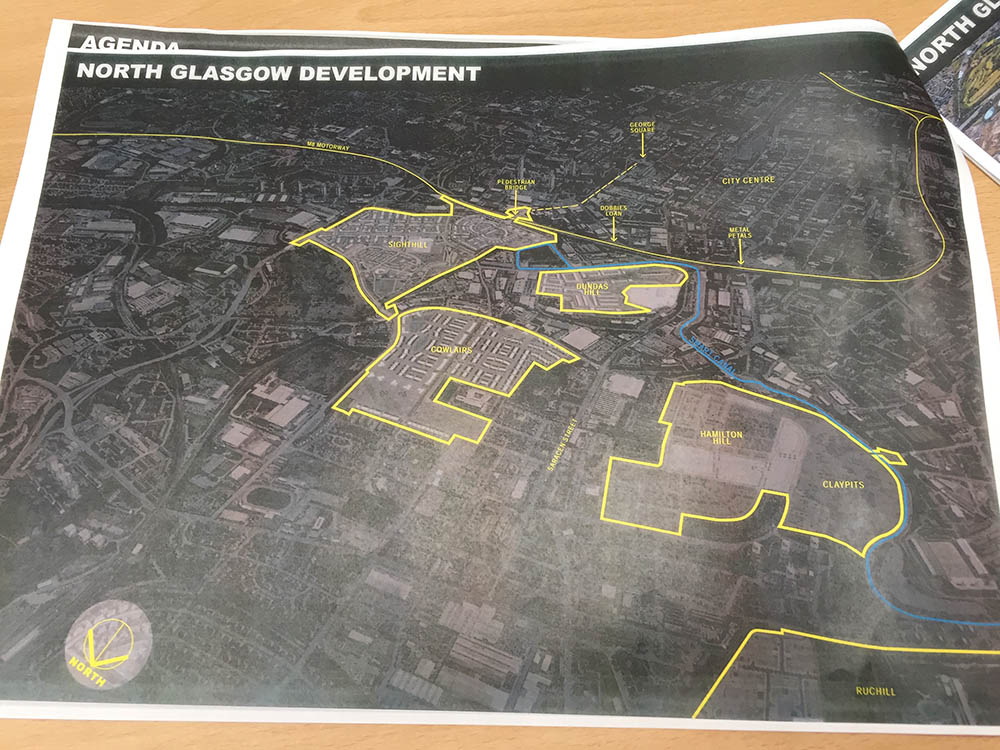

Map showing new developments across North Glasgow: Top of map shows city centre, areas outlined in yellow are new development sites. Photo by Melissa Garcia Lamarca

From majority social to private housing amidst arts-based canal regeneration

Aside from Sighthill, neighboring sites nestled immediately next to or near the canal have had social housing demolished over the past few decades, with residents displaced to other parts of North Glasgow and the city. Major new housing developments are planned for or already being built on these sites. In total, over 3,000 new homes are being built in the canal area, with 20% of new residences slated for social housing and the remaining 80% for private development. The majority of the private homes are for purchase, with average prices of around £200,000, far more than what deeply impoverished local residents can afford. Some social housing will also be mid-market rent, a tenure category targeted towards people who are being squeezed out of the private rental market and are unable to buy but don’t qualify for social rent. This significantly reduces social housing provision for the most impoverished groups, instigating housing campaigns in places like Hamiltonhill and, more recently, Maryhill.

Vigil for social housing by Wyndford Tenants’ Union, part of Living Rent Tenants’ Union, on a former Maryhill housing estate now slated for private development (November 2020). Photo by Nick Durie.

These new housing developments are starting amidst a large-scale regeneration project of Glasgow’s canal spearheaded since 2006 by The Glasgow Canal Partnership, a joint venture between Scottish Canals, Glasgow City Council and the architecture/development firm Igloo, specialized in brownfield and post-industrial sites across the UK. Their “arts-based” regeneration approach is one that has been proclaimed a success by these actors and the private sector. While it won a 2018 award for quality in planning from the Scottish Government, the initiative generated a new community of arts professionals disconnected from the history of the area and its long-term residents. As part of the broader improvements to the blue-green canal infrastructure, the 6.7 hectare Claypits Local Nature Reserve was created as a linear park alongside the canal. It will simultaneously enhance existing recreational space and provide a surface water drainage solution for the regeneration of vacant and derelict sites.

New towpath along the canal near Speirs Wharf. The old industrial building on the right was renovated in the 1980s to be high end housing. At the back of the photo are The Whiskey Bond (TWB) creative co-working building and Scottish Opera’s new headquarters. Photo by Melissa García Lamarca.

A dubious partnership with local residents

The way “sustainable transformation” and “massive regeneration” in North Glasgow is taking place depends on who you talk to. Keep in mind that many long-term residents have been displaced with the demolition of Sighthill and Hamilton housing estates especially. This despite the well-established understanding of environmental costs associated with demolition. A local housing organizer and resident also explained that many who remained do not keep up with the canal’s regeneration, nor are they involved in the arts-based activities. People have bigger day-to-day worries like the transformation of the UK’s social security payments through the controversial roll out of Universal Credit, losing their housing benefits or other dimensions of lived austerity. A 2007 survey conducted by Scottish Canals found that half of all residents of Maryhill, a neighborhood bordering the canal, did not even know the canal existed. This finding also reflects the physical disconnect and historic neglect of the canal network.

On the other hand, Glasgow City Council views itself as working in partnership with the local community on the new housing developments. Several public consultations have taken place, where people can place sticky notes on plans to express what they want or need. Many local residents and workers we spoke with were quite critical of these consultation efforts. Overall, they were seen as tokenistic, delivered in a top-down fashion and with few locals present in relation to the plethora of Council employees.

With hundreds of millions of public funds being poured into the massive regeneration and development of the built environment along Glasgow’s canal, there will undoubtedly be an influx of higher income residents into this historically deprived area. Researchers have called mixed communities gentrification by stealth. An influx of higher income residents is exactly what the Council wants, since creating mixed income communities is their policy approach to Transformational Regeneration Areas in general. Yet for now, it seems that aside from 20% social housing provision in new developments (hardly an even ‘mix’), few measures exist to ensure low-income and people of colour will be meaningfully included—socially, economically and politically—in the regenerated green and sustainable canal area.

__

Melissa García Lamarca is a human geographer and a postdoctoral researcher at BCNUEJ, where she explores the financial dynamics underlying urban greening, the relationship between development and greening, and community resistance to greening projects. She is a housing activist and member of the Radical Housing Journal editorial collective.

Neil Gray is an urban researcher and housing activist based at the University of Glasgow. His work primarily focuses on urban regeneration, devaluation, social housing and class composition. He is an active member of Living Rent Tenants’ Union and the author of Rent and its Discontents: A Century of Housing Struggle (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018).

Top photo: Sighthill housing estate during its demolition. Photo by Neil Gray