By Margarita Triguero-Mas

Gentrification spurred by urban renewal in the form of new parks and riverfronts have sparked a housing crisis with few solutions in sight.

Editors’ note: This post is the first of the Series “Green inequalities in the city”, developed in collaboration with the Green Inequalities blog, and which seeks to highlight new research and reflections on the linkages between the dominant forms of “green” redevelopments taking place in cities and questions of urban environmental justice, and the challenges and possibilities these imply for more just and ecological urban spaces. The series contributions will be published every first and third Tuesday of each month.

—

Denver’s large-scale urban transformations over the past decades have had profound impacts on housing conditions, especially for residents of colour. Parks have strongly influenced this transformation, with 21 parks completed between 1975 and 2001. Following an economic boom in the late 1990s fueled by ultra-cheap office rents, a well-educated labour force, and economic development funds, Denver became a magnet for investment that gradually transformed its urban fabric and demographic makeup. Since then, the physical implementation of Denver’s green aspirations was often made possible by large-scale development plans and renewal projects. The ensuing urban and transit-oriented development focused on clean-up projects on brownfield (contaminated ex-industrial) sites along Denver’s river shores, which facilitated their conversion into “attractive” areas for investment. These projects began to change the face of neighborhoods like Highlands, Union Station, West Highlands, Five Points and Lincoln Park, displacing working-class families that were being substituted by young professionals from Denver suburbs and other parts of the country. As a result, housing costs have risen dramatically, detonating a housing crisis with no significant solutions in sight.

Displacement, homelessness and gentrification

Despite the 2007 foreclosure crisis that interrupted Denver’s transformation, the city quickly recovered in the 2010s, when an increased demand for highly skilled workers resulted in the displacement of Black-African-American and Hispanic-Latinx residents, which represent 30% and 9% of Denver’s population, respectively. In fact, Denver leads the nation in displacing the largest Hispanic-Latinx population. Displacement expanded beyond downtown-adjacent neighbourhoods, along the riverside to historically more marginalized areas like Globeville or Elyria-Swansea.

Along with New York, Seattle and San Francisco, Denver possesses the highest rental spikes in the country, having increased by 46% between 2011 and 2016 and by an additional 15% by March 2017. According to lead economist for the Colorado Futures Center at Colorado State University, the metro area’s chronic shortage of affordable housing is expected to peak in 2018 at about 32,000 units. Additionally, Denver county registered nearly 3,500 homeless residents in 2018.

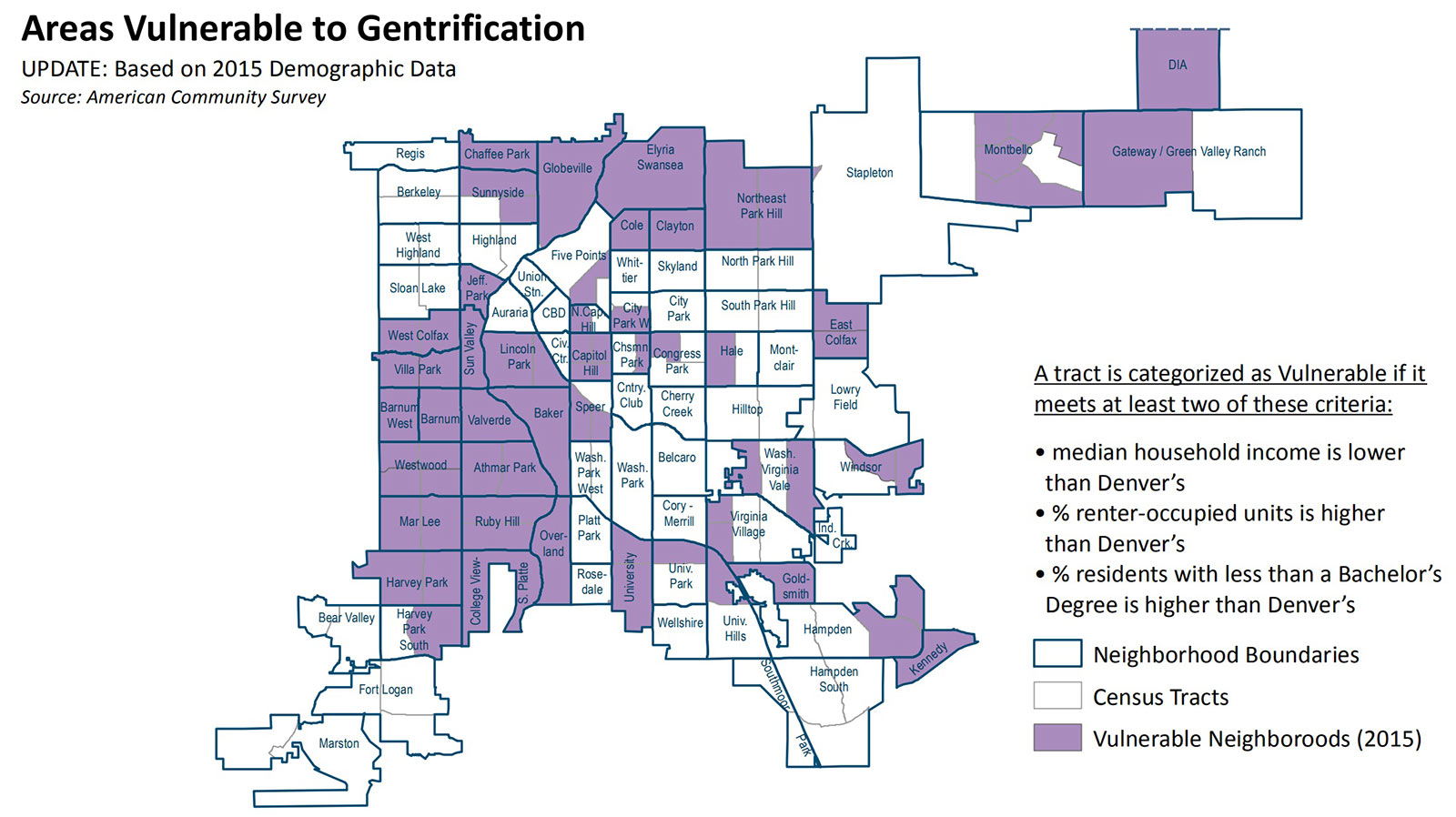

Denver neighborhoods vulnerable to gentrification, according to 2015 data. Source: Denver Government

Local stakeholders disagree on the sources of the housing crisis. While most of the members of the administration and development sector interviewed in June 2019 for our GREENLULUS project considered that the leading factor was the high demand for housing, some community organisations say that the housing stock is simply unaffordable.

Regardless, the current housing crisis has contributed to physical displacement of residents and mass homelessness. Much of this impact is concentrated along a West-North axis commonly referred to as the inverted-L, known for its poor quality of health, education, income and housing, and home to some of the city’s most controversial cases of gentrification. Indeed, this gentrification, driven by “urban renewal” initiatives, is another crucial factor associated to the worsening of this housing crisis. These initiatives include: the rebranded RiNo Art District, that brought funding for the creation of new parkland and other urban green spaces and whose new name disregards Five Points’ traditionally black cultural identity; the improvements to Argo Park in the predominantly Latinx Globeville neighborhood, and in Elyria-Swansea, the motorway expansion, several improvements to Durham park and Heron Pond, the new 39th Avenue Greenway, and the redevelopment of the National Western Complex. In Globeville and Elyria-Swansea, the South Platte river revitalization—which has led to the creation of several new parks and redevelopment of others—has also fostered this gentrification.

Stress and psychological trauma linked to redevelopment projects, displacement and housing vulnerability has emerged as a significant health problem in gentrifying areas. Mental health and community impacts are even more extreme if we consider homelessness and its extreme criminalization in Denver, where the 2019 camping ordinance has generated some of the most dramatic housing incidents.

Left: Construction site of the new 39th Avenue Greenway in Denver’s Elyria-Swansea neighborhood, 2019.

Right: Nicknamed “RiNo,” the trendy River North Art District features contemporary art galleries, a beer garden and hip concert venues in revamped ex-industrial buildings.

Photos by Margarita Triguero-Mas

Seeking transformative solutions to address the housing crisis

While state legislation does not allow municipalities to impose rent control, efforts at the city level to increase protections for tenants have included improvementsto the anti-discrimination ordinance, community-focused credit lines, and other policies like increased minimum wage for city workers and support for small businesses.

Many stakeholders advocate for zoning changes as a possible remedy, while others push for creative though sometimes questionable solutions like tiny homes for the homeless, Accessory Dwelling Units, housing cooperatives such as Queen City, and social impact bonds. Although efforts like these remain marginal, perhaps those with the biggest potential are being led by community groups like one from the predominantly Latinx-Hispanic neighborhood of Athmar Park, which is using the Blueprint Denver plan (which incorporates equity to provide housing recommendations, among others, for an “inclusive city”) to push for a zoning plan that protects the community’s residents, and the neighbourhood preference program that designates priority to displaced residents in accessing new housing.

Despite all these efforts, however, Denver’s economic growth and associated green gentrification continues to pose a threat to its lower income and minority residents. While the actions mentioned above may mitigate these effects, their eventual implementation for many may be too little too late.

Top picture: Love This City Denver mural by Jason T. Graves, Pat Milbery, and the So-Gnar Group. Source: carriecolbert.com

—

Margarita Triguero-Mas is a postdoctoral researcher at BCNUEJ and an affiliated researcher at ISGlobal. Bridging the fields of public health, urban planning and environmental justice, her research at BCNUEJ aims to reveal the social effects of urban planning policies that aim to build healthier cities.

One Comment