Institutional investors have become the dominant shareholders in the largest gold mining companies, with implications for their activities.*

In the early 2000s, institutional investors (highly capitalised financial players such as hedge funds and pension funds) have increasingly turned to owning gold mining companies as a form of speculative investment. In a context of rising gold prices, holding gold mining stocks (thus speculating on the value of future production) was perceived as providing a higher return on investment than owning the gold bullion itself.

During the course of the 2003-1011 commodity boom, the investor base of gold mining companies has shifted. Institutional investors now own the largest gold mining companies holding from 50% to 80% of their shares.

The Toronto Stock Exchange, a key site for mineral financing. Source: Kurtis Garbutt

The financialisation of the mining gold corporation

Institutional investors are known in the financial sector for their ‘activist’ approach to investment. By the sheer size of the capital they manage (holding a minimum of $100 million dollars, according to the US Securities and Exchange Commission), these investors tend to intervene more in the way companies are run than individual investors. Their strong bargaining and voting powers gives them capacity to influence on issues such as shareholder value creation.

Shareholder value creation means that the performance of stocks and dividend returns (money paid back to shareholders) are the overarching goal of firm activities. Under this framework, company decisions on investments are assessed on the basis of what it can bring to stocks and dividends rather than to growth per se. Shareholder value creation signals the ‘financialisation’ of the corporation as its interests are re-aligned to the financial interests of institutional investors.

Some of the large financial players that were drawn to the gold mining industry include high-profile hedge funds such as Blackrock, Paulson Co. and Soros Fund Management; these now hold significant shares in the world’s largest gold companies. The dominance of these types of investors in stock-exchanges and within large corporations reflect the concentration of produced wealth and money-capital in these entities.

A photo of financier George Soros, the Chairman of Soros Fund Management. Source: Heinrich Böll Stiftung

The changing face of extraction

Institutional investors became key sources of mining industry financing during the commodity boom. In particular, gold mining companies were at the forefront of some of the largest equity offering as the price of gold rose from US$300 dollars per ounce in early 2000 to nearly US$1,900 dollars in September 2011.

Figure 1. Gold price fluctuations over 1970-2015. Data series from 30 January 1970 to 29 April 2016, based on London PM fixe. In US dollars. Source: World Gold Council

In response to the high demand of institutional investors for gold mining stocks, gold companies issued new shares. For instance, the world’s largest gold producer – Barrick Gold, made two of the largest equity offers in the history of the Toronto Stock Exchange: US$4 billion and US$3 billion dollars in 2009 and 2013, respectively. Other gold companies followed suit, using the proceeds to fund multi-million mergers and acquisitions in the industry and to expand their activities during the boom years.

As institutional investors (and hedge funds in particular) expect higher returns, companies ensure that a growing share of company earnings is returned to shareholders through dividends. Dividend payments have gone up, with industry reports estimating a compound annual growth rate of 16 per cent.

Shareholder value creation also has important implications for the mines and projects that comprise companies’ operations. The sale or closure of profitable mines and the laying-off of workers have been part of this strategy, as each mine and project are assessed based on stricter financial guidelines. For example, companies had to factor in investors’ political risk tolerance and expected returns on invested capital in order to proceed with a project’s development (author’s interview, March 2014).

Challenges for the movement of resistance

Such developments carry important implications for countries that follow an extractivist model for development, and crucially for those pushing for a shift away from this model. The ‘value’ generated from extractive activities, for instance, must accommodate shareholder demands, amid already heightening and competing claims coming from labour unions, affected communities, and the state, in the form of increased wages, compensation, taxes, and royalties.

The distribution of value is a contentious terrain that companies must negotiate. But as the industry becomes even more tied to financial markets and its health gauged on the basis of its investment returns, firms are under pressure to slosh greater value back to financial investors as the ‘first in line for profits’.

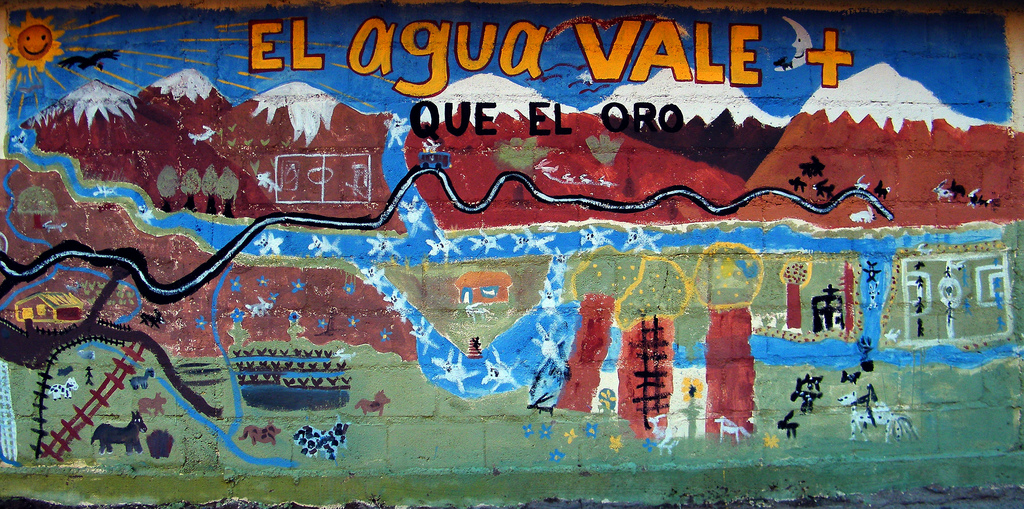

A mural taken in Northern Chile, protesting Barrick Gold’s Pascua Lama project. Source: Amilcar.

This implies that the presumed scale where struggles and conflicts are imbricated needs to be re-thought and re-scaled. As illustrated here, the institutions that prop up this extractive model, that move and shape extraction in particular ways, are located in places far from where physical extraction takes place.

Yet the interventions of these actors and their particular motives are critically transformative of livelihoods, the environment and the territory. That ‘conflicts over extraction are never only local’ rings true, as the capital deployed and the value it generates are entangled in processes of accumulation in key financial centres. This makes the case for strengthening alliances between civil society organisations and movements, and across regions (e.g. between Latin America and North America) to bolster local campaigns and deal head on with the global dimension of mining.

* This post is part of a series sharing chapters from the edited volume Political Ecology for Civil Society. Julie’s chapter contribution with the original title ‘Who owns the world’s largest gold mining companies and why it matters?’ is included in the chapter on disaster capitalism. We are eager to receive comments from readers and especially from activists and civil actors themselves, on how this work could be improved, both in terms of useful content, richness of examples, format, presentation and overall accessibility.