By participants of the ‘Anthropology and Degrowth’ Workshop.*

Why should Anthropology engage with Degrowth, and why should Degrowth engage with Anthropology? This post offers a set of reflections around these questions, based on the contributions to the workshop “Anthropology and Degrowth: Deepening the dialogue”.

Introduction

By Gabriela Cabaña, Lucia Muñoz-Sueiro, Lorenzo Velotti, Andrea E. Pia

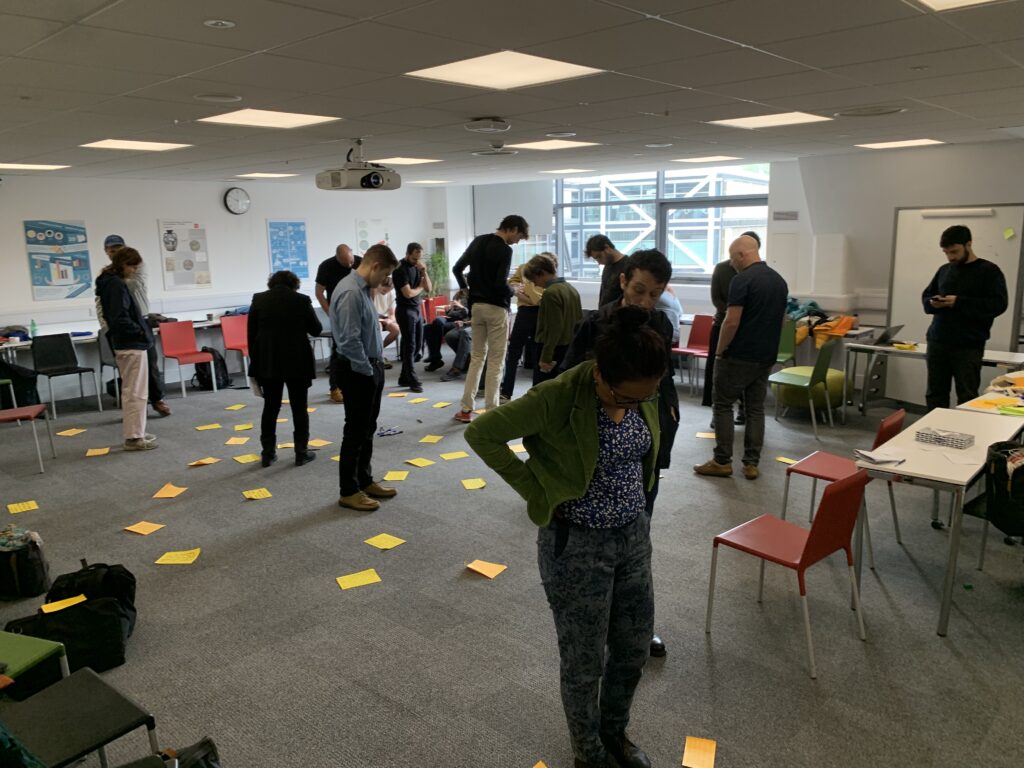

The workshop Anthropology and Degrowth: Deepening the dialogue took place at the London School of Economics and Political Science (London, UK) on the 5th and the 6th of June 2023 thanks to a generous LSE Research Infrastructure and Investment Fund grant. As the organisers of this workshop, we offer a brief introduction to the following four pieces, which are the result of collaborative writing during the workshop. Our call for abstracts received an enthusiastic response with over 30 submissions, and we welcomed contributions from authors at different career stages, engaged in theoretical or applied research projects and stemming from a range of different disciplines. In light of the overwhelming response, we adapted the original format of the workshop to make it academically fruitful but also playful, inclusive, and as non-hierarchical as possible.

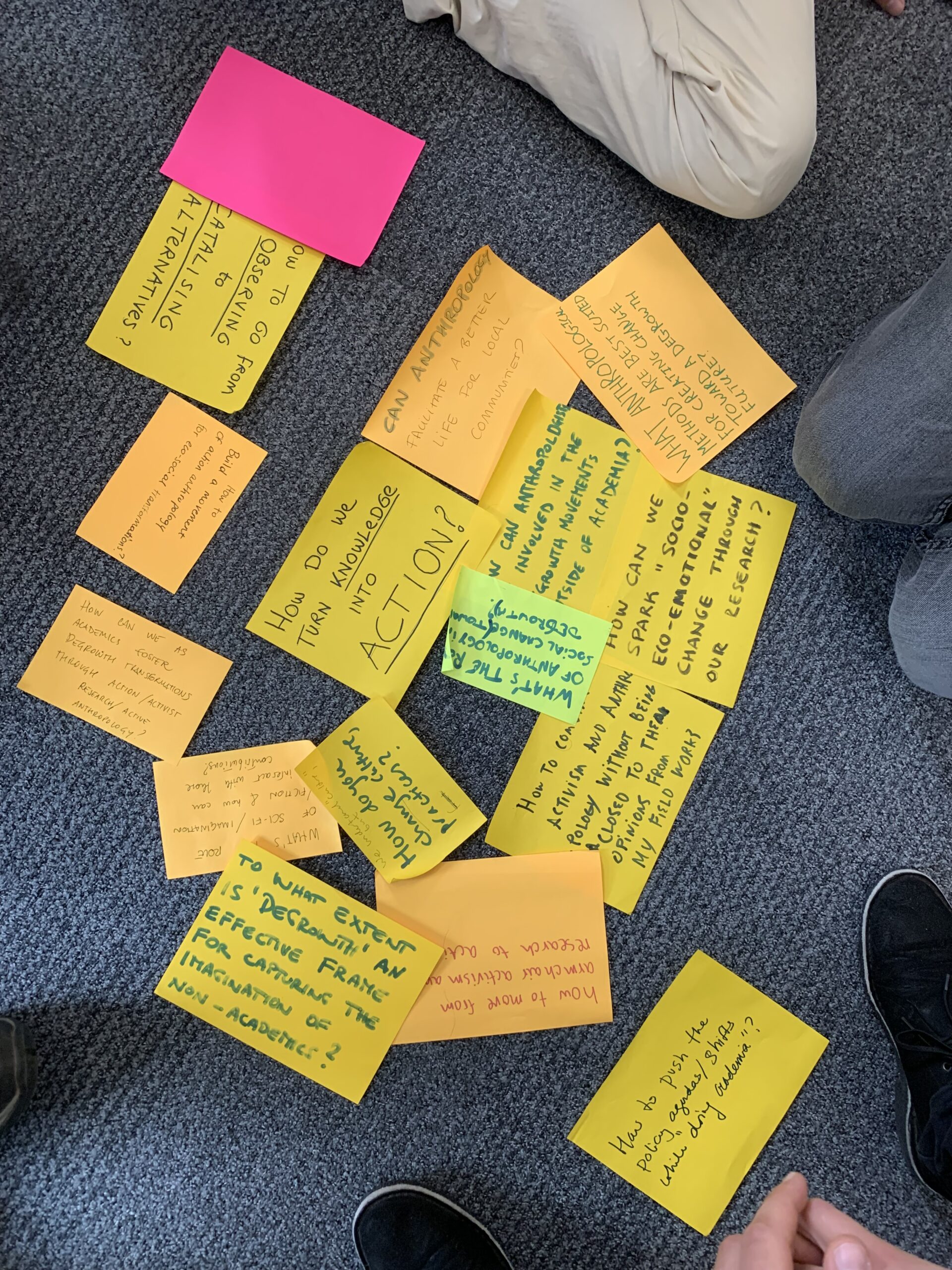

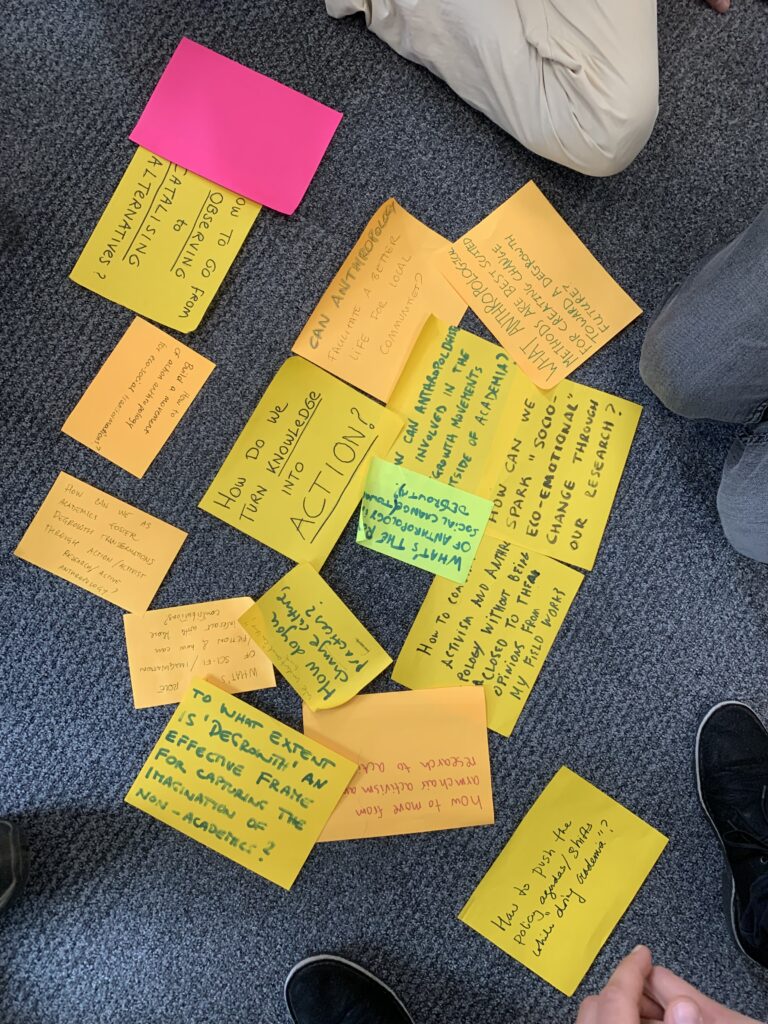

Among the unconventional activities enriching the workshop, we spent the second day in London clustering research questions and reflecting together about our positionality as anthropologists engaging with degrowth and/or degrowthers engaging with anthropology. We divided participants into four groups for a collective writing exercise. Four texts were produced this way: the first one inquires about how anthropology can contribute to the degrowth project without becoming colonial; the second reflects on what it means to take growth as an object of study; the third piece investigates different possible configurations between anthropology and degrowth; and the final one gives methodological suggestions on anthropology’s relation to growth and degrowth projects.

Coloniality, anthropology and degrowth

By Cristobal Bonelli, Emilie de Bassompierre, Franca Marquardt, Adrien Plomteux, Gregory Prescott, Rano Turaeva, and Ritu Verma

As the anthropologist Jason Hickel has argued, colonialism, as a political, economic and ideological project, laid the historical foundations for delivering what is now called economic growth, measured in gross domestic product (GDP). In concrete terms, the Global North’s GDP expansion has been largely at the expense of people in the Global South. Beyond the geopolitical project of colonialism, it is important to consider coloniality more generally. The latter notion, introduced by the Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano, refers to a certain form of ideological domination via hegemonic narratives that serve to maintain power dynamics, snuff out marginal or dissenting voices, and limit possibilities for autonomous action. Differentiating between the process of historical colonialism and the notion of coloniality in general, is central to decoloniality debates.

Anthropology, once associated with the colonial project, has evolved to potentially play an important role in anti-colonial struggles. With its unique knowledge and methods, anthropology enables to bridge cultural gaps, critically examine power dynamics, and reflect on their own position within them. Through ethnographic research, anthropology offers insights into how capitalist growth is experienced in diverse contexts and explores alternative conceptions of the desirability of development and growth projects.

Because of it and beyond mapping a pluriverse of cultures, anthropology can further assist in fostering constructive dialogue, on a more equal footing, between communities of the ‘majority’ and ‘minority’ worlds. Anthropology has a history of reflections on politically committed anthropology. The aim here is to collaborate, not for the North to “help” the South, or vice versa. This can only bolster movements seeking to address historical North-South injustices through reparations.

From its origins in a European setting, degrowth has adopted a critique of hegemonic ‘imaginaries’, in particular that of growth-centric economism. It views present-day forms of coloniality as part of a larger global capitalist logic, ultimately driven by the imperative of growth. It is deeply critical of a collective fixation with GDP, a fixation now extending to most corners of the planet. Growth-centric capitalism is equally linked to the systematic negligence of non-human lives and ecosystems, as the concept “imperial way of living” – developed by Brand and Wissen 2012 – explains. In the midst of what scientists like Gerardo Ceballos and colleagues, among others, have discussed as the 6th mass extinction, we need to question the violence exerted by humans over other beings, wherein the latter are turned into resources for extraction and exploitation. We must shift towards a collaborative and respectful relationship to non-humans and humans alike.

As in the case of anthropology, there are real concerns about the degrowth movement’s ability to engage in meaningful dialogue with the majority world. Some point to internal power dynamics within the movement. Others are critical of degrowth’s perceived inability to relate to and leave room for other non-growth narratives. Without doubt, degrowth has blind spots: it can do better when it comes to engaging with debates occurring in the majority world and with acknowledging the dynamics of power inherent in such discussions.

To discuss decoloniality within degrowth movements therefore leads us to ask how the movement itself reproduces coloniality: by side-lining voices from movements with which they could be in solidarity; by being largely dominated by white males; by promoting only policies that apply to the North (e.g. universal basic services); by not foregrounding policies that take aim at the interdependencies of growth, colonialism and coloniality (e.g. debt cancellation). Degrowth is still organised around movement intellectuals, and still largely confined to university settings in the North. This is a problem that can only be solved by building stronger alliances with social and ecological movements centred in the majority world.

A fertile starting point for global alliances stems in questioning the ideologies and institutions of economic growth. We must confront those holding power in this system, with the top 1% possessing the same wealth as the remaining 99%. This concentration of power is enabled by the narrow focus on GDP and legitimised by growthism. In this, Global South movements are leading the way: see for example the Debt for Climate campaign and the recently released Bogotá Declaration.

The pursuit of GDP growth has historically relied on unequal global exchange and the exploitation of both ecosystems and labour. As an alliance, our objectives should include decolonising supply chains, supporting local autonomy, and preventing corporate dominance over diverse livelihoods and ways of life. The degrowth movement has embraced these critical perspectives and political positions. However, to establish better alignment between decolonisation and degrowth, we must critically examine the assumptions and internal organisation of the degrowth movement itself. Such introspection is essential for fostering resonance between the projects of decoloniality and degrowth.

Understanding growth

By Soumyajit Bhar, Peter Sutoris, Ahac Meden, Michael Degani, Ieva Snikersproge, Mechthild von Vacano, Pauline von Hellermann, Gabriela Cabaña.

Why does the imperative of economic growth seem so hard to break with? Part of this answer lies in the mobilising powers of growth as a project that invites everyone to partake, promising prosperity for all. Even though we see this promise broken by rampant social injustice, we remain invested in it. And even as the climate crisis confronts us with the finitude of our plant and its cycles of regeneration, the imperative of growth remains in place, only that it’s now dressed in green.

Growth draws its mobilising powers from its resonance with our everyday experience; many good things grow. For that reason it works as an open signifier, as a container for a range of different ideas and projections of what it really is and how it could–or why it should–be achieved. Anthropologists can play a role in disaggregating different growth dynamics and tracing their interrelation. Key to this endeavour is the distinction between two different, yet often conflated understandings of growth: one that we identify as ‘growth rooted in life’—which relates to the growth of, for instance, plants, or children, and refers to the material foundations of nature—and one that is ‘growth rooted in numbers’ which finds its expression in shareholder or GDP reports and capital accumulation. Within the former, growth is always limited, as it is followed by decay, forming a constant cycle of life — regrowth. Only in the latter, growth is imagined as limitless, as an ever-climbing curve.

Growth rooted in numbers is a system beyond our direct experiential grasp. It catches us in its whirlwind. Sometimes on the boom end, sometimes on the bust. There is a geopolitical distribution to this variety of growth—it is often people in the global south who are on the bust, something that anti-imperial critics and theorists of underdevelopment such as Bunker and Magalhães Teixeira saw with acuity. However, as revealed by foundational insights of Marx, there is also a constant characteristic of growth rooted in numbers: it is powered by the self-revolutionising nature of capital, which always takes more than it gives. As shown by Marxist feminist scholars in the 1970s and 1980s, growth-powered economies externalise – that is, draw upon, exploit, and devalue – care work. Such economies have now reached a scale and pitch that the suffering externality is the planetary life support system itself.

When we talk about and defend growth, we believe we are talking about one and the same thing, but – through the process of reproduction of capital – growth rooted in numbers is undermining growth rooted in life, i.e., flourishing communities and natural systems. A promising way forward then would be recentering the dynamics of growth rooted in life – exertion, energy, expansion and contraction – in both people’s working lives and in the metabolism of the living world. This might, for instance, involve prioritising maintenance and repair of the built environment, or instituting a reduction of the working week (but not wages) to expand time for rest and what we will; it might involve legislating the agroecological principles of fallowing soil or the controlled burns of indigenous fire management–all practices that promote flourishing through cyclical alternation.

Anthropology will continue to have a role in exploring what this system looks and feels like ethnographically, in different situated locales, but to step up to the challenge thrown by degrowth scholarship, it must do it in a comparative perspective: Why and when do we misrecognise growth rooted in numbers for growth rooted in life? How do we account for forms of Keynesian nostalgia, rooted in productivist heteronormativity? How do we account for the popularity of more recent libertarian fantasies of limitless acquisition that cluster around figures like Elon Musk or Peter Thiel, clowns who get to break all social rules or vampires who devote staggering amounts of money to their bloodless posterity? What does it mean to live in a world capable of producing, moving, and wasting commodities of mind-boggling scale—of palm oil, concrete, copper, lithium, data? What can we learn from how the conceptual abstraction of growth is represented in different languages? These, we think, are the key lines of inquiry for understanding growth rooted in numbers, and, by extension, something very basic about our shared planet in the 21st century.

Two approaches to degrowth: anthropology of (de)growth and degrowth anthropology

By Paula Escribano, Donatella Gasparro, Agata Hummel, Graham Janz, Lucía Muñoz-Sueiro, Gerardo A Torres Contreras & Lorenzo Velotti.

Degrowth stems from a radical critique of the study and practice put forward under the umbrella term of international development and/or sustainable development. Concurrently, anthropology, as a social science, holistically examines social culture and approaches the history of societies. In developing the concept of degrowth, Serge Latouche drew inspiration from classical economic anthropologists such as Marcel Mauss, Marshall Sahlins, and Karl Polanyi. The study of development is one of the subdisciplines within anthropology. But, unlike anthropology, both degrowth and development are political agendas, representing normative theories that prescribe specific means and ends for society. To delve into the relatively unexplored relationship between degrowth and anthropology, it is helpful to consider what we’ve learned from the relationship between anthropology and development. This relationship has long been problematic, to the extent that James Ferguson referred to them as “evil twins.”

Socio-cultural anthropology and development share common origins in the nineteenth century evolutionary thinking. Initially, these conceptual foundations resulted in the linear classification of societies, originating in and perpetuating colonialist endeavours. However, this framework has been extensively problematized and critiqued within the field of anthropology. In contrast, international development organizations and initiatives have utilised this evolutionary theoretical paradigm to design interventions informed by normative ideals, establishing such framework as a political and practical agenda. And it must be acknowledged that the field of applied “development anthropology” has actively engaged in such agenda. In this context, degrowth shares the overall goal of human development as a political agenda, yet it diverges significantly by criticising the usual growth-oriented approach of what normally goes under the “development” label. Moreover, degrowth explicitly seeks to politicise socio-environmental issues, while development has been famously labelled as “the anti-politics machine” by James Ferguson.

In the face of the pressing socio-ecological crisis that currently confronts us, the role of anthropology in engaging with degrowth becomes paramount. If anthropology fails to address the urgent socio-ecological issues at hand, it risks disconnecting itself from the collective imperative to safeguard a sustainable environment for future generations. Time is of the essence as society races against the clock to avert the transgression of irreversible biophysical limits and the catastrophic consequences they entail. We must align both social and natural sciences with the preservation of life, and anthropology’s knowledge should likewise contribute to this cause. Hence, we are compelled to consider whether we are witnessing a historical movement that necessitates anthropology’s active participation in driving change.

Suppose we engage in an exercise of imagination, envisioning anthropological knowledge being utilised in service of degrowth within “overgrown societies”, by which we mean societies in which GDP, resource use, and emissions (among other indicators) have overcome ecologically sustainable levels. In that case, we can recall instances from the context of the USA’s imperialist expansion where anthropologists ventured into the political realm and raised their voices for transformative change. These instances sparked debates about the boundaries of the discipline and how to address pressing social issues. Some notable examples include Franz Boas’ letter in 1919, in which he denounced the employment of scientists as spies serving the bellicose aims of the USA. In 1948, Margaret Mead initiated a series of discussions concerning the limitations of applied anthropology, ultimately leading to the establishment of a code of good practices. In 1971, Eric Wolf and Joseph Jorgensen denounced the use of anthropology for military purposes in Thailand and renounced their positions within the Ethics Committee of the American Anthropological Association (AAA).

When addressing the complex association between anthropology and development, Arturo Escobar provided a valuable distinction between development anthropology and the anthropology of development. Similarly, Giallian Hart made a distinction between “big D” Development, signifying development as a deliberate intervention project, and “small d” development, representing an uneven process of economic change. Drawing upon these two categorizations, we posit that anthropology can adopt two approaches to engage with the concept of degrowth.

First, the “anthropology of (de)growth” approach examines both the significance of growth in people’s lives and the phenomenon of degrowth as a social movement. For what concerns the former, it would surely address those hidden desires for collective prosperity and individual accomplishments that are not fully captured by the economistic language of growth (plenitude, prosperity, flourishing, concepts variably highlighted across indigenous/pastoralist/peasant cultures worldwide). Regarding the latter, degrowth is not employed as an analytical concept, but rather as an emic concept — that is, used by common people — to be thoroughly analysed. Drawing from the longstanding engagement of anthropology with radical social movements, this approach aims to uncover hidden structures, symbols, social relations, categories, and other elements that can shed light on the practice of degrowth. Degrowth manifests in diverse ways on the ground, representing a world where many worlds fit or functioning as a political project aiming to scale down the economy.

Second, the “degrowth anthropology” approach emerges as a direct engagement with the degrowth objective within countries and classes experiencing overgrowth. It operates as an engaged anthropology, employing a scientific approach while maintaining a distinct focus on societal impact. This approach necessitates making commitments to the urgency and necessity for change, guided by a degrowth agenda and advocacy. The purpose of degrowth anthropology is to instigate, consolidate, and champion social change towards an ecologically and socially just global society.

When anthropologists engage in the act of “studying up” — investigating the power structures that exist above us, such as the prevailing growth ideology as part of capitalist class hegemony — they should not hesitate to keep the anti-hegemonic prescriptive agenda of degrowth in mind. Conversely, when anthropologists undertake the act of “studying out” — examining the lives, creations, or struggles of those involved in viable alternatives — they should, as David Graeber eloquently puts it: “try to figure out what might be the larger implications of what they are (already) doing, and then offer those ideas back, not as prescriptions, but as contributions, possibilities—as gifts”. In essence, it may be more fruitful to set aside any inclination towards prescribing and instead engage in a critical, reciprocal, and enriching dialogue with the individuals and communities with whom anthropology interacts.

Anthropology and militant research

By Emma Marzi, Wiebe Heetvelt, Maria Montesino, Sean Farmelo, Angelina Kussy, Nicolas Loodts, Domenico Volpicella.

We explored this relation reflecting on how anthropologists can be catalysts of change towards degrowth, both during the process and aftermath of research practices. We came up with some points that build on existing literature on the topic of militant and engaged research (Setha and Merry 2010, Choudry 2013, Sanford and Angel-Ajani 2006, Hale 2006), that we summarise here:

- Participant observation implies a true meeting with others, a true understanding without arrogance. It’s about understanding the other person’s point of view in depth, and avoiding instrumentalisation.

- An engaged action oriented approach can uncover a deeper understanding. Being situated in movements as researchers is a way to work against the top down imposition of theories and instead co-create them, specific to the cultures, industry, locality or geographies we are working in.

- The communities we work with are dealing with the realities of transition right now. The resources and time which is available to academics in the institutions should be shifted and made available to movements where possible.

- Researchers’ positionality should be clear and transparent, both during research and in final works. When are one’s own values represented and when are the values of others? Stating one’s position could be done in a strategic way in order to make the research and outcome more militant.

- It’s very important to keep recognising the knowledge people already have to promote their initiatives through horizontal and not hierarchical processes to co-create mechanisms of social reproduction, more independent from the global capitalist market economy.

- Mediation facilitates spaces and practices where a person or a collective proposes to work on a specific topic/problem in their environment and other people can join in to develop it in an open and collaborative way.

- Embracing a multidisciplinary approach is key. We need to engage with other fields of study to enrich the dialogue with, and not about, the subjects of research.

A militant form of research requires speaking with the research partners on the results that are being co-constructed, building a feedback mechanism. By doing so, the people involved can confirm the accuracy of the knowledge, correct or add points that have been overlooked. These dynamics allow the integration of different knowledge and experiences, always from a horizontal approach, without establishing hierarchies. In the aftermath, we should acknowledge the ongoing commitment researchers have to the communities they study and have been a part of. We could do so by:

- Reaching those politicised differently. Be useful for society in general and not only contribute to academia or already organised social movements. Share anthropologist knowledge about non-capitalist and non-productivist ways of living.

- What is found on the field often unveils the needs of communities. These data can be translated into ‘formal’ papers or proposals that influence policy-makers.

- Network building research, action & dissemination — building a network of researchers, artists, writers, directors, journalists etc. to disseminate, and promote these attempts of living in a different way.

- Communicate with imagination. We have to go beyond the scientific article as a unique result of a research, and multiply the outcomes in an original, multimodal way: producing non-academic papers, web-documentaries, co-signed texts or books, and attending citizen assemblies. Apply pressure so the academic system recognises these results.

- Be instrumental in giving voice to people who are hidden or excluded from public attention.

- Knowledge should be accessible to a broad audience by communicating findings through artistic media, such as film screenings, music performances, events in public spaces or exhibitions.

Finally, a short collective reflection on the setting of the conference

Signed by all the contributors.

LSE is a renowned academic institution and we appreciate the symbolic value of a workshop on anthropology and degrowth held on its premises. Nevertheless, we would like to highlight that, in the same institution, there are some visible indications of the colonial perpetuation of a racialised division of labour and the symbolic violence associated with it. On the one hand, our discipline requires that we constantly reflect on our practices. This includes awareness of our surroundings, and even more so inside academic institutions. On the other, at the core of the degrowth movement lies a struggle against all axes of injustice. We support the mobilisation of LSE Halls of Residence cleaners represented by the UVW (United Voices of the World) and we are concerned with the predominant whiteness of this academic setting.

—

*Participants/authors:

Dr. Soumyajit Bhar straddles action and academic research with more than 15 years of experience (both volunteering and full-time) working with various environmental and sustainability issues. He joins the School of Liberal Studies at BML Munjal University as one of the founding Assistant Professors. He was an Assistant Professor at Krea University, where he taught courses at the intersection of Environmental Studies and Psychology. He holds a Ph.D. in Sustainability Studies from Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE) as part of a unique interdisciplinary Ph.D. program. His dissertation attempts to understand socio-psychological drivers and local and regional scale environmental impacts of conspicuous/luxury consumption basket in India. Soumyajit is furthering postdoctoral research at the intersection of rising consumerism, sustainability concerns, and inequality levels in the context of the Global South. He has published in international journals and popular media. He is also interested in larger questions of philosophy and ethics, particularly pertaining to environmental issues.

Gabriela Cabaña is an Anthropology PhD candidate at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Her research focuses on the relation between work and energy, and the moral value we assign to productivity. Her doctoral fieldwork was in Chiloé, south of Chile. She is part of Centro de Análisis Socioambiental and Degrowth London.

Paula Escribano is a social anthropologist based at de Department of Social Anthropology at the University of Barcelona and at the Rural UOC Network at the Open University of Catalonia. She is working on the impact of state over-regulation and neoliberal policies on the agrarian transformation and currently leading the research project ‘Livelihood strategies, neoliberalism and environmental values’, funded by Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. She has been a visiting researcher at the Political Ecology Group in the Institute of Social Sciences, Netherlands, has been directing and producing ethnographic documentaries. (www.paulaescribano.com) ORCID: 0000-0002-4635-3325

Donatella Gasparro is a PhD candidate and instructor at the Institute for Geography of the University of Münster, Germany. Her research focuses on revaluing rurality and subsistence practices for socio-ecologically desirable futures, starting from rural areas of the South of Italy, through engaged ethnographic methods. She teaches and researches at the intersection of political ecology, materialist ecofeminism, degrowth and rural geography.

Dr. Pauline von Hellermann is a Senior Lecturer in Anthropology at Goldsmith, University of London. Combining political ecology with historical ecology approaches, she has researched forest governance and landscape change in Nigeria and Tanzania and most recently the global environmental anthropology of palm oil, during a Leverhulme Major Research Fellowship (2018-22). She is also a climate activist and seeks to promote the role of anthropology in regeneration and transformation.

Agata Hummel is an anthropologist and Assistant Professor at the Institute of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Warsaw. Her theoretical interests are particularly anthropology of development, post-development perspective, economic and political anthropology. She is interested in social movements, rurality and public policies. She does her fieldwork in Latin America and Europe.

Graham Janz is an unaffiliated independent researcher and homemaker.

Dra. Angelina Kussy, anthropologist and political activist interested in social reproduction, critical studies on labour and social care, municipalism, post-growth and the commons. Currently, she collaborates in the research project CARE MODEL at the Rovira and Virgili University, teaches at the UManresa and works for the Opus Independents, social enterprise creating for the common good, where she coordinates the network of laboratories for the Universal Basic Income and the Neighborhood Democracy Movement.

Franca Marquardt is a visual anthropologist currently based in Leipzig, Germany. As a researcher, she is focused on social movements and expressions of solidarity for a good life for all. Trying to find ways to combine visual experiments and research to evoke change.

Ahac Meden is a PhD candidate in Anthropology at the Postgraduate School ZRC SAZU in Ljubljana, Slovenia. For his doctoral thesis he is researching the Role of digital Humanities for Sharing Knowledge in Public Scientific Institutions, conducting ethnography among a group of Slovenian linguists and the linguistic data they live. He works at the Institute of Cultural History ZRC SAZU as the co-editor responsible for Popular Culture, Media Art and New Media, and as the technical web editor on the project of the New Slovenian Biographical Lexicon (NSBL).

María Montesino is a sociologist, researcher and agroecological producer. She is currently working on her PhD on new ruralities, culture and food sovereignty at the Department of Sociology and Social Work of the University of the Basque Country. She is specialised in participatory processes and methodologies, citizen laboratories and cultural mediation. The basis of her research work is the communal use of land, the ecosocial transition in food production and degrowth processes focused in rural areas and peasant communities. She is a member of the Spanish Federation of Sociology in the Research Committees of Sociology and the Environment, Rural Sociology and Sociology of Gender. She collaborates regularly with various cultural institutions and universities in the fields of anthropology, sociology, political ecology, culture and ruralities. She is part of La Ortiga Colectiva where she directs the art, literature and thought magazine La Ortiga.

Lucía Muñoz Sueiro is an anthropologist and PhD candidate at the Institute of Environmental Sciences and Technology of the University Autonomous of Barcelona, with Masters at The New School and Columbia University (Fulbright and La Caixa scholarships). Her research focuses on temporalities and tradition in relation to degrowth in the Iberian Peninsula. She is a member of Research and Degrowth (R&D).

Andrea E. Pia teaches anthropology at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He is the author of Cutting the Massline: Moving Water and the Political in Southwest China (2024, JHUP). He is one of the editors of the open access journal Made in China.

Adrien Plomteux is a PhD candidate at University College London. His research centres around the concept of ‘frugal abundance’ and aims to better understand how to live well without much consumption through fieldwork in rural and indigenous communities in Iceland and Kenya. He is a member of the editorial collective of the Degrowth journal and a founding member of Degrowth London.

Ieva Snikersproge is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Neuchâtel. She has studied various activist initiatives that its protagonists understand as alternatives to capitalism. Her current research project, supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation, centers on the back-to-the-landers in France and their endeavors to construct post-growth economies within the capitalist world-ecology.

Dr. Rano Turaeva is an affiliated and habilitating lecturer at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in Germany. She authored two monographs, one on Uzbekistan (2016, Routledge) and one on Russia (in preparation). She co-edited two books, one on mobilities and informality and the second on halal markets. She edited two special issues, one published with Extreme Anthropology Journal on Anthropology of Debt relations and another one together with Michael Brose on Halal economies. She has been writing on the topics of debt relations, informal economies, informality and urban transformations in post-Soviet cities, migration, entrepreneurship, gender, among many other topics and publishing in Extreme Anthropology, Cities, Nationalities Papers, Inner Asia, Asian Ethnicity, Communist and post-Communist studies, Sociology of Islam, Central Asian Affairs, Central Asian Survey, Anthropology of Middle East among other journals.

Dr. Mechthild von Vacano is a social and cultural anthropologist with the University of Freiburg, Germany. Her research interests lie at the intersection of economic and psychological anthropology, with a regional focus on Indonesia.

Lorenzo Velotti is a PhD candidate at the Faculty of Political and Social Sciences at the Scuola Normale Superiore. His doctoral research is an ethnography of care politics in commons’ movements in Naples and Barcelona. He holds a Msc in Anthropology and Development from the London School of Economics and Political Science. He is a member of the Centre on Social Movement Studies (COSMOS) and of Research and Degrowth (R&D).

Dr. Ritu Verma is an adjunct professor at Carleton University and associate professor at the College of Language and Culture Studies, Royal University of Bhutan. Working at the intersection of the anthropology of development and environmental anthropology, her ethnographic research focuses on the political-ecology of land, labor and natural resources in Madagascar, Kenya and other locales. Her recent research investigates the geopolitics and apparatuses of development financial institutions, and ways development and climate change is experienced by pastoralists in Bhutan. She is currently exploring degrowth, post-growth and wellbeing alternatives from a decolonial and activist lens.

Dr. Domenico Volpicella is a cultural anthropologist and ethnographer. He is finishing his PhD with the University of Western Australia (Perth) looking at degrowth values and practices in a group of native, heritage and rare poultry breed farmers from Australia and Italy. His interests are in alternative economies, climate change and sustainable food production.

Michael Degani is Assistant Professor of Environmental Anthropology at the University of Cambridge, and the Juliet Campbell Fellow in Social Anthropology at Girton College. He researches the politics of energy, infrastructure, and design in Africa and beyond, and is the author of The City Electric: Infrastructure and Ingenuity in Postsocialist Tanzania (Duke University Press, 2022).