By Laura Pottinger, Arianna Tozzi, Erin Beeston, Alison Browne, and the Cottonopolis Collective, University of Manchester

The exhibition LITMUS: Environmental Legacies of Cotton was created by artists and interdisciplinary researchers for the British Textile Biennial 2023. In this essay we introduce the Cottonopolis Collective and LITMUS, asking what histories can be made visible, and what new knowledges might be created in the process of collecting materials, handling, analysing and making textiles together.

The Cottonopolis Collective and research

Within its much celebrated ‘innovative past’, Manchester – its industries, private businesses, universities, and cultural institutions – were key strategic nodes in the expansion of the United Kingdom’s colonial aspirations. The cultivation of cotton, and the scientific, industrial and agricultural knowledges associated with this crop and commodity, were central to British industrialization and colonial expansion. As the epicentre of the cotton trade, the city became known as ‘Cottonopolis’ in the nineteenth century. However, this industry had far reaching impacts on people and places globally, leaving complex environmental legacies. The Cottonopolis Collective, brings together an interdisciplinary team of historians, human and physical geographers, social and environmental scientists, cultural organisations and multi-disciplinary artists working with textiles, botanical materials and film, to interrogate and unsettle Manchester’s role as the first industrialising city. This research questions the expansion of global cotton markets through environmental science, which ultimately provided the cultural and scientific authority that underpinned colonial expansion, frontier agriculture, and colonial urbanization across the globe.

Unearthing material legacies

LITMUS: Environmental legacies of cotton is a new exhibition developed for the British Textile Biennial. Held every two years in Lancashire, in 2023 the biennial explored the environmental and human costs of the global textile industry over the last two centuries. Textile production boomed in the historic English county of Lancashire due to the wealth of natural resources in the form of coal fields and waterways, along with unprecedented migration and urbanisation. Manchester, to the South of the historic county of Lancashire, grew significantly as a centre for trade in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Such was the spectacle of the ‘Cottonopolis’, political philosophers came to observe Manchester. In 1844, Leon Faucher declared Manchester was the spider at the centre of a web of cotton manufacturing towns, highlighting its role a central node.

The exhibition charts the development of a year of interdisciplinary and arts based exploration with cotton. Its central piece, LITMUS, is a series of large scale textile hangings created by Natalie Linney, which aims to unearth and unpick the material and environmental consequences of colonial cotton science, agriculture and industry.

Between April and July 2023 Natalie Linney was the artist-in-residence in Geography at the University of Manchester. Working closely with the Cottonopolis Collective and Geography Laboratories, this residency gave Linney and the wider team the time and resources to explore cotton and its legacies in more depth, and to create a series of large-scale pieces that were exhibited in the weaving shed at Queen Street Mill in Burnley, Lancashire as part of the British Textile Biennial 2023.

Lengths of cotton displayed in the Weaving Shed at Queen Street Mill, Burnley, Lancashire. Credit: Joe Smith.

Detail of cotton fabric imprinted with rust. Credit: Joe Smith.

As a textile artist specialising in eco-print, Linney is fascinated by the potential for revealing layers of social and environmental inequalities on fabric. In this new work, Linney creates an unsettling multisensory piece that draws the cotton at the centre of this industry into conversation with impacted soils, water, and plants from sites integral to the colonial project within Cottonopolis.

To create the work, long pieces of twill fabric, which were made from raw cotton spun and woven at nearby the National Trust’s Quarry Bank Mill, Cheshire, were buried in various locations around Manchester for just under two months. Locations included a park alongside Queensland Road, Gorton; Pomona Island, close to the Manchester Ship Canal; and spaces within the University of Manchester such as a 200 year-old compost heap at the Firs Environmental Research Station in Fallowfield.

Unearthing buried fabric at Pomona Island. Credit: Joe Smith.

The site of a 200 year-old compost heap at The Firs Environmental Research Station, Fallowfield, Manchester. Credit: Joe Smith.

Fabric unearthed at Quarry Bank Mill, Cheshire. Credit: Joe Smith.

Some pieces were concealed in polluted earth, or in land belonging to institutions that were critical to the cotton industry. Others were suspended and exposed to the elements (and pollution) on roofs and in rivers. Diverse locations were chosen to connect with the complex and multiple ways that the legacies of cotton are embedded within the fabric of the city and surrounding areas; and to represent our complicity in the ongoing impacts of colonisation elsewhere. The remnants that we unearthed are marked by processes of microbial action and industrial contaminants, and pigmented by the earth and plant matter of each specific site.

Fletcher Moss Park, Didsbury, close to the site of the former Shirley Institute, a centre for cotton research in Manchester. Credit: Joe Smith.

Fabric unearthed at The Firs Environmental Research Station, Fallowfield, Manchester. Credit: Joe Smith.

This process of burying and revealing these large strips of cotton resonates with scientific approaches to determine soil health, and methods associated with the Shirley Institute, a centre for cotton research in Manchester. By burying strips of cotton fabric, the resulting cellulose decomposition can be assessed to understand the processes at play within the soil. Burying cotton also speaks to the urgent need to unearth the sedimented, multi-layered histories of this industry and to reveal troubling legacies that have been hidden from sight.

Unravelling global histories

Across the Cottonopolis research, the interdisciplinary team has explored the environmental histories of cotton in archives at the University of Manchester and the Manchester Museum’s Herbarium as well as other institutions across the city of Manchester, online archives and global media on cotton science, agriculture, business and industrial development. In addition to Linney’s large scale textile pieces, the exhibition draws together different strands of this research which begins to untangle the myriad of ways that industrial Manchester impacted people and environments in the UK and globally, while calling into question the environmental knowledges created.

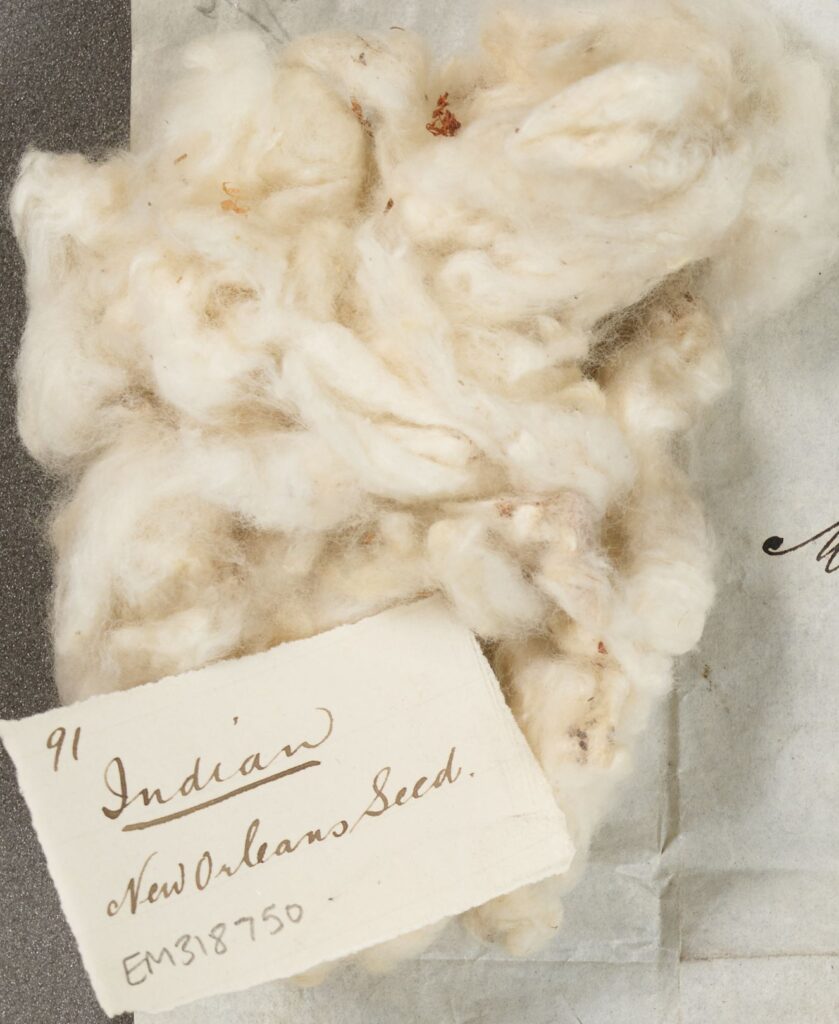

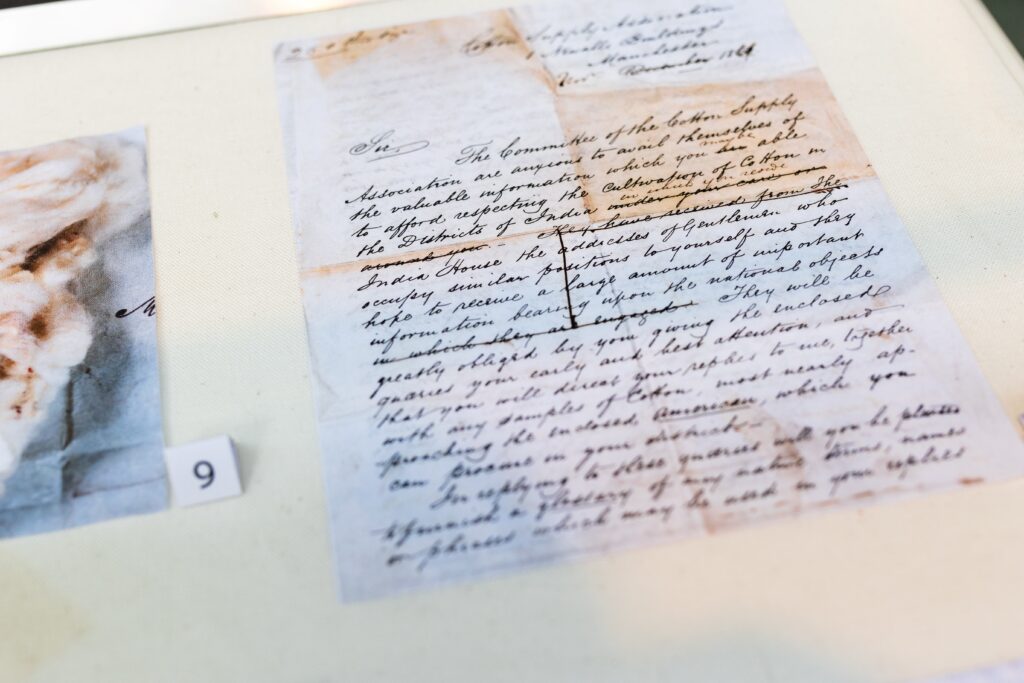

For example, the Cotton Connections cabinet illustrates the vast international network involved in the transfer of cotton knowledge through objects and archival materials. Curated by Erin Beeston, and drawing on her archival research, it shows the tangible effects of Manchester trader’s efforts to diversify their cotton supply, which led to the spread of non-native cotton seeds across the British Empire and beyond – a form of ecological imperialism. The purpose for these experiments was to find regions, ideally within the Empire, that could cultivate cotton from New Orleans Seed, reducing the need for American grown cotton, as the Civil War (1861-1865) loomed. Seeds, along with written instructions and images on glass plates showing how to cultivate cotton, were sent to British Imperial administrators by the Cotton Supply Association (founded in 1857 in Manchester).

Indian Cotton, New Orleans Seed from Manchester Museum’s archives. Credit: Erin Beeston.

Objects studied in the Manchester Museum include cotton bolls returned to Manchester from across the empire, including examples from India and Australia, and beyond the Empire such as Morocco and Syria. The cabinet also contains examples of cotton sent back to the Association, the instructions they sent out, and evidence of correspondence with influential Manchester merchants. Images of cotton bolls displayed here include some cultivated in India from New Orleans seed. India was a particular focus of the Cotton Supply Association’s efforts. As outlined in their own history (written in 1871), their primary aim was: ‘nothing less than a complete revolution in the modes of cultivation… in India’.

Letter (facsimile), penned by Secretary of the Cotton Supply Association in 1864 displayed in the Cotton Connections cabinet. Credit: Joe Smith.

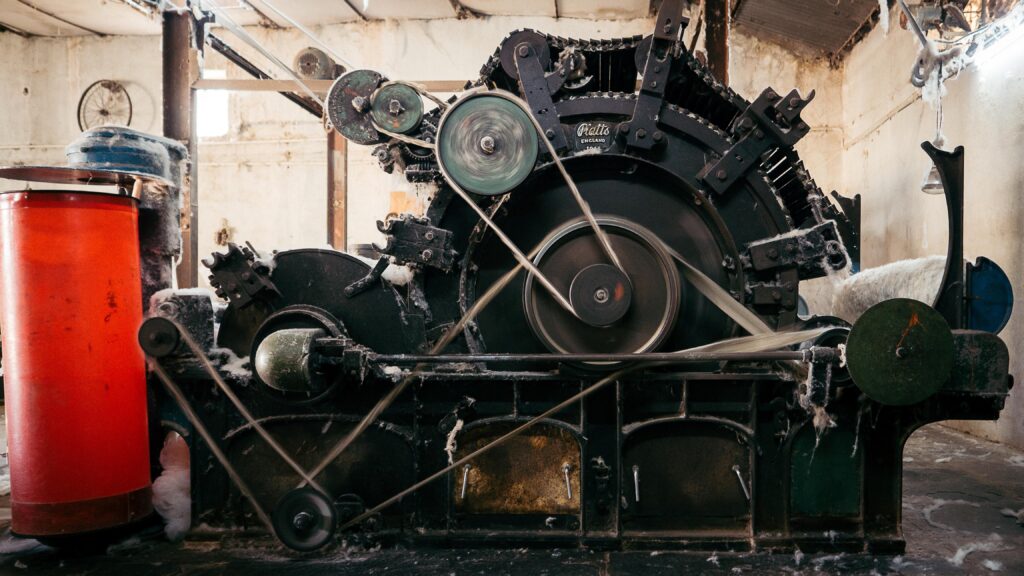

Cottonopolis Turns East: Following the threads of India’s cotton curated by Arianna Tozzi brings together archival material and photography to narrate the story of Vidarbha, an agrarian region in central India, and how it was transformed into a cotton-growing hub during British rule. Photographs on display show how cotton processing machines manufactured in Manchester during colonial rule and left behind after Indian independence from Britain are being repurposed by a local organisation to process indigenous cotton. These local indigenous varieties are being reintroduced in response to the agrarian crisis in the region galvanised by the monocrop cultivation of genetically modified Bt Cotton – an input-intensive crop associated with capital intense and risk prone agriculture practices.

A carding machine manufactured in Bolton, England. Gram Sewa Mandal, Wardha, Maharashtra. Credit: Adam Barr.

The So-Called Queensland cabinet, curated by Alison Browne depicts some of the strong and problematic evidence collated by the Cottonopolis Collective of Manchester and Lancashire’s complicity in cotton driven frontier agricultural expansion with devastating impacts on land, waters and people around the Nerang River, in so-called Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia. It is important to acknowledge that these lands and waters are the sovereign, stolen, unceded, lands of the Kombumerri people of the Yugambeh nation. Archival research is beginning to explore links to institutions in Manchester (such as the Mechanics Institute, a precursor to the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology) where early visions of a new colony of Queensland as a place to develop ‘slave free’ cotton were shared amongst industrialists.

Manchester interests were key to the development of the southern frontier of the Queensland colony. This included slave-owning families such as the Muir’s who retreated from the US and then moved to create the Queensland Manchester Cotton Company Estate (Gleeson, 2020); the strategic emigration of workers from Lancashire cotton industry to Queensland following the Lancashire cotton famine to Queensland as labourers; and the establishment of worker cooperatives in Queensland (the Lancashire and Queensland Cotton Growing Cooperative Society). This archival evidence leads us to question how people and institutions within Manchester and Lancashire can begin to engage in processes of repair and reparations with places such as south-east Queensland, to the sovereign Yugambeh people whose lands and waters were stolen in these processes of frontier agricultural expansion, and for families who can trace their roots to those forced to ‘blackbird’ (indentured labour) on Queensland cotton and other related agricultural plantations (sugar).

Stitched sampler by Alison Browne (stitched with Queensland Cotton on Quarry Bank Mill woven cloth processed Natalie Linney) displayed in the So-Called Queensland Cabinet. Credit: Joe Smith.

Interdisciplinary textiles experiments

The exhibition also charts the development of the creative collaboration, featuring pieces produced in two arts-based pilot workshops held in autumn 2022 which set out to connect the work of the Cottonopolis Collective with ongoing research on slow textile making at the University of Manchester. In these workshops, textile artists Natalie Linney and Hayley Caine, and film maker Alastair Lomas joined researchers to explore a variety of so-called ‘natural’ dyeing techniques. Inspired by the idea of a litmus test – a universal, dye-based indicator of pH level, derived from lichen – the objective was to examine what these colourful processes could potentially show us about environmental impacts of the cotton industry.

With guidance from the Manchester Geography Laboratories, the team gathered samples of river sediment which were then analysed to understand their heavy metal content. A series of playful, arts-based experiments followed, working with plant-based dyes, archival materials from Manchester Museum and woven cotton fabric from the National Trust’s Quarry Bank Mill. This included experimenting with making anthotypes – alternative photographic images of cotton materials from Manchester Museum’s archives; creating botanical eco-prints; and modifying plant-based inks and cotton swatches with metal solutions. Each process involved working with plants and soils gathered from rivers affected by historic textile industry pollution in Greater Manchester.

Cotton swatches dyed with plants collected at polluted rivers sites, modified with metal solutions. Credit: Joe Smith.

A short film documents these early site visits, discussions and workshops. It focuses on the ideas and discoveries that came about as a result of bringing expert practitioners of the physical sciences, social sciences and arts together in a relatively unstructured environment that encouraged play, exploration and experimentation. These interactions raise questions about how legacies of environmental ruination can be visualised and communicated through slow, collaborative creative processes. But they also prompt consideration of the novel environmental understandings that might develop through interdisciplinary textiles methods themselves.

Following multiple threads through collective/connective stitch

There are inherent challenges for both artists and researchers working as part of a large, interdisciplinary team, investigating a complex topic in which there are many different strands. To explore how collective textile making might help to connect the diverse threads running in and out of the research, members of the academic team have begun stitching together into the fragmented cloth exhibited at the British Textile Biennial using cotton sashiko thread dyed with botanical materials. These include plants gathered at the cotton burial sites (willow and equisetum – or, ‘horsetail’ – from Queensland Road, bracken from Quarry Bank Mill, weld from Pomona Island). Threads have also been dyed with edible spices and lentils sourced in India by members of the Cottonopolis Collective during research visits (turmeric, chilli, garam masala, urad dal and ratanjot or ‘dyer’s alkanet’).

Equisetum gathered at Gorton Park, Queensland Road, used to dye threads and fabric. Credit: Joe Smith.

Cotton sashiko threads dyed with gathered plants and spices. Credit: Joe Smith.

Lengths of cotton fabric buried at Pomona Island displayed as part of LITMUS at the British Textile Biennial 2023. Credit: Joe Smith.

By following creases and areas of wear and decay in the unearthed cotton fabric, these initial experiments in stitch encourage reflection on the reparative potential of collective textile making and mending. How, for example, can we think together with communities impacted by cotton production drawing on textile and materials focused research methods? While this work has started with a close engagement with environmental places and processes within Manchester itself, the Cottonopolis Collective see this as the beginning of an expansive arts-science research programme. Together, the team is continuing to explore how interdisciplinary and creative methods can help us think about the global histories of the cotton industry, and how we can begin to address these legacies and responsibilities both near and far.

Acknowledgements: The Cottonopolis project was funded by Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC); the Making, Dyeing, Materialising project by The University of Manchester Research Collaboration Fund; the Research Fellowship Making Slow Colour and Artist Residency in Geography by the Simon Endowment Fund; and PhD research by the Royal Geographical Society Postgraduate Research Award. The project has also been generously supported by Manchester Museum, Quarry Bank Mill National Trust, the University of Manchester Geography Laboratories Teams, the University of Manchester Makerspace, the wider Cottonopolis Collective and other colleagues at the University of Manchester.

With thanks to: Abi Stone, Aditya Ramesh, Alastair Lomas, Alisha Quinn, Alison Browne, Andy Speak, Anke Bernau, Arianna Tozzi, Aurora Fredriksen, Benedict Gretton, Chris Jackson, David Browne, David Polya, Dongyang Mi, Erin Beeston, Franciska de Vries, Gareth Clay, Hayley Caine, Jane Wood, Jenna Ashton, Joe Smith, John Moore, Johnny Huck, Jonathan Yarwood, Kerry Pimblott, Laura Pottinger, Laura Richards, Lindsey Loughtman, Mark Usher, Martin Dodge, Natalie Linney, Natalie Zacek, Nathaniel Millington, Polyanna da Conceição Bispo, Rachel Kenyon, Rachel Webster, Rebecca Self, Richard Bardgett, Sami Pinarbasi, Suzanne Kellett, Tom Bishop, Xuehan Zhou, and staff from the British Textile Biennial and Queen Street Mill.

Dr Laura Pottinger is a Research Fellow in Human Geography at the University of Manchester, with an interest in people-plant relationships and everyday forms of social and environmental activism. Her current project, Making Slow Colour, looks at processes of natural dyeing, and works closely with textile artists, to investigate the relationship between slow, creative practice and environmental care.

Dr Arianna Tozzi is an environmental human geographer at the University of Manchester, UK. Her research focuses on the intersecting impacts of climate change and processes of agrarian transformation in rainfed areas of Maharashtra from feminist and decolonial perspectives.

Dr Erin Beeston is a Knowledge Exchange Research Fellow at the University of Manchester, Creative Manchester and Manchester Histories. Erin is an historian with a background working in North-West UK museums with rich textiles collections. She has an ongoing interest in the relationship between material culture, memory and historical narratives in both academic and public histories.

Professor Alison Browne is an environmental geographer at the University of Manchester leading research and teaching on everyday practices, governance and infrastructures (water, sanitation, waste, etc); humanities, arts and social science methods; decolonising disciplines and institutions including two-way knowledge collaborations with Noongar Elders and Community, University of Manchester and Manchester Museum.

Featured image: LITMUS at the British Textile Biennial 2023. Credit: Joe Smith.