By Riccardo Buonanno

The new sci-fi epic Dune is a planetary narrative. Human affairs only represent a part of a whole geopower, in which Planet’s forces organize, incite and deform social and political relations. Is it time to reconsider our certainties on the human agency facing environmental crisis?

After leaving the movie theatre screening Dune, the latest in Hollywood sci-fi colossal, directed by Denis Villeneuve, a weird feeling has taken hold of me. It regarded my incapacity to sympathize with any of the main characters. Yet, I adored the movie and its design and arrangement, its mise en scène: I spent two hours and half holding my breath, completely fascinated by the screening. I have been asking myself about the reasons behind such contradictory reaction. It looks to me like I enjoyed a sensational audiovisual inclined plane wherein everything had to happen, whether the characters want it or not. The story did not flow as the product of human actions, conflicts and desires. These were channelled into something else. Then, I realized. I could not have felt empathy with human movie heroes because there is no human hero. It is not human agency that moves the narrative. The question arises: who if not the Human is the agent?

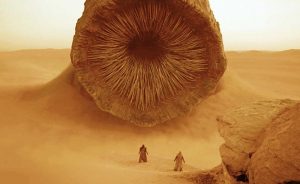

Arrakis. Photo: Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

Let’s try to give account of the plot. Apparently, Dune tells of an interstellar colonial enterprise and environmental destruction. A feudal-like humanity, whose basic political organizations are aristocratic families, is involved in the conquest of Arrakis, a desert planet inhabited by the indigenous population of Fremen. The storyline revolves around the struggle between two families for the control of the planet. The reason why Arrakis is so contended lies in the dispossession and the exploitation of the melange, a mysterious element of the desert that is used as fuel for spacecrafts, among other things.

We entered into this universe through the eyes of Paul Atraides, the teenager son of Leto, the chief of an influential family in the galaxy, and Lady Jessica, an acolyte of the Bene Gesserit, a sisterhood that nurtures political aims throught non-human physical and mental abilities. Paul himself is the result of a centuries-long Bene Gesserit’s eugenics program to create an other-than-human superbeing: an embodiment of his ancestors’ memory capable to bridge space and time in a single dimension. A being Bene Gesserit plans to use to gain direct control over the universe. Paul realizes that his actions has not to do with the common notion of human free will. Dreams and hallucinations announce him that his choices are channelled in a wider and pre-existing path constituted of the blood network woven by Bene Gesserit. He accepts the actualization of these past spiritual forces throughout his body. It is just the start of his going with the Inhuman flow.

Paul Atraides and Lady Jessica in their journey through Arrakis’ desert. Photo: Warner Bros. Picture/Youtube

By Inhuman, I mean all that determines and exceeds the human, what figures as creative and inventive in it, those impersonal forces ‘we summon up rather than control’, as put by Elizabeth Grosz. Inhuman is a condition necessary to the constitution of subjectivities, as a ‘trajectory immanent within the human’. Thus, the dyad ‘human and inhuman’ has to be replaced by the copula ‘human is inhuman’, and vice versa.

That resonates with the consideration concerning the other main character of the movie, Arrakis. Dune is a planetary narrative. Human affairs only represent a small part of a whole geopower, in which the Planet’s forces organize, incite and deform social and political relations. In Arrakis, humans need to complement the planetary field of immanence in order to survive. The most iconic of its creatures, the giant sandworm, appears in the desert only if attracted by a repetetive sound, destroying its source. It has an extraordinary, and killer, sensibility for what Henri Bergson would have defined as the measurable discontinuity in the pure duration. Human steps on the sand and the harvesting machine of the melange evoke the sandworms. One can safely walk through the desert only by moving to its rythm, that of the sand and the animals living there.

Having learnt this movement is the reason why Fremen, Paul and Lady Jessica can inhabit Arrakis. In the journey with his mother through the desert, Paul perceives such a complex equilibrium of the Planet. That is evident in the emotional climax of the movie, which sees him running away at the edge of an aircraft. Paul decides not to directly fly its aircraft and to abandon himself to a sand storm, managing to survive. Paul Atraides, as well as Fremen, does not domesticate the Planet.

The Giant Sandworm. Photo: Warner Bros. Pictures/Youtube

In Dune, Paul and Arrakis illustrate what some scholars would call uncommoning, a concept which unveils the unseen of the Anthropocene and questions the Human as the core principle of transformation. Besides, commons and enclosures both figure as the result of conflicts among humans, wherein the objectification of Nature at the hands of Men persists. The unseen of the Anthropocene showed by uncommoning stands for the emerging together of human and extrahuman nature: an heterogeneous assemblage of life that would render visible ‘an ecological entanglement needy of each other’. While writing that Paul, as well as Fremen and Lady Jessica, are uncommoning with Arrakis, I mean that they perform in a processual entanglement with planetary forces. In other terms, Paul does not transcend the coexistence of human and non-human nature within his subjectivity. His actions and his thoughts are enmeshed in the Oneness represented by Arrakis.

Dune brings to the screen the planetary realm as a process subtending political and social transformation supposed to be led by Men. Seeing this movie as a popular narrative imbued with critical ecological thought helps in re-signifying the image of agency in the middle of environmental crisis. This narrative dislocates agency from the interior will, consciousness and historical positions of Humans in the making of a Common world. However, it is not just a matter of shifting agency from human to extrahuman entities. Rather, Dune vividly renders the making of a Common ecology wherein agency pertains to those planetary forces that figure as the conditions and capacities for life.

That does not signify the end of politics and the falling into inaction. As a participant in the wider becoming of Arrakis, Paul is enmeshed in a multiplicity of non-controllable agentic forces and, at the same time, involved in the invention of the new. Besides, Arrakis proves that transformation is not a particular human capability. Paul’s abandonment to the Planet and to other-than-human Bene Gesserit’s plan represents a creative difference, since it opens the field to Fremen’s resistance, as we will see in the sequel. The Inhuman agency of commoning shifts environmental politics from being conceived as a problem to be solved by Men as a reaction to alienating and destructive forces, to a field of strategic experimentation wherein freedom means the affirmative being party to a planetary process. The Inhuman making of the Common provides lenses to see at manifestations of an already shared world, constantly opened to the invention of the new, with or without the Human and its conceptuality.

—

Riccardo Buonanno is a political theorist with research interests in the realm of Political Ecology, New Materialist Theories and Process Philosophy. He is currently developing his PhD at the Centre for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra, Portugal ([email protected]).

One Comment