By Hanbyeol Jang and Kimberley Thomas

Tourism and black pig booms on Jeju Island in South Korea threaten groundwater, the only freshwater source on the island. Is it possible for tourism, black pigs, and clean groundwater to coexist without compromising the island’s future?

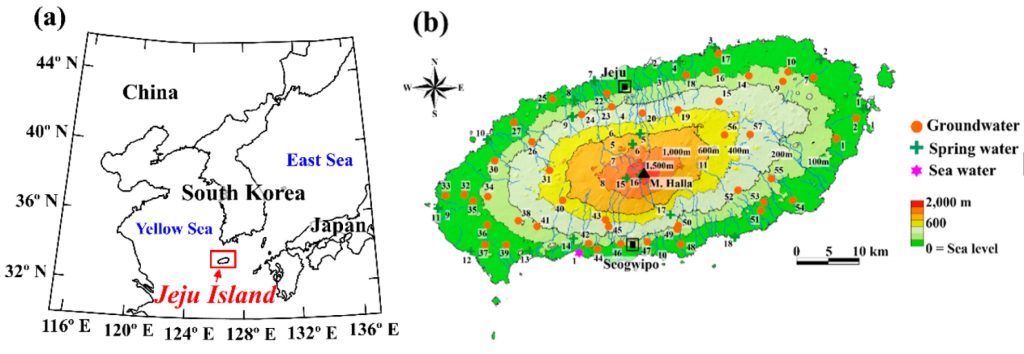

Groundwater is an essential resource. Apart from ice and snow, groundwater accounts for the largest fraction of freshwater resources on the planet. Geographically isolated islands rely more heavily on groundwater than mainland areas. Jeju Island in South Korea is a prime example of the importance of groundwater to remote islands (Figure 1). Except for a few small reservoirs, groundwater is the only freshwater source on this island of nearly 700,000 residents. Created by volcanic eruptions between 1.2 million years ago and 25,000 years ago, Jeju Island’s peculiar geology features highly porous basalt soil and numerous geological passages called ‘Soom-gol’ that connect the surface to the groundwater. Therefore, while surface water is scarce, groundwater is bountiful. However, the tourism and black pig booms are threatening this vital resource.

Figure 1: The location of Jeju Island and the brief distribution of groundwater. Source: Lee at al., (2020)

Tourism Boom in Jeju Island

Jeju Island is well known to Koreans as a premier honeymoon destination, and its economy is highly dependent on tourism. The Island’s volcanic activity and warm climate contribute to beautiful and exotic landscapes that attract visitors to the island. These distinct natural values have been recognized globally, with Jeju Island being selected as a ‘World Natural Heritage Site’ (2007) and ‘Global Geopark’ (2010) by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Since 2013, more than 10 million domestic and international tourists have visited Jeju Island annually (with the exception of 2020 due to COVID-19).

Moreover, the Bank of Korea reported in 2020 that more than half of Jeju’s economic revenues are generated by tourism-related sectors. In addition to soaking up the island’s natural splendor, tasting local delicacies is a must for visitors as well. According to public opinion research on Jeju’s local foods, tourists reported a strong preference for black pig meat.

Black Pigs in Jeju Island

Although the black pig’s history in Jeju Island dates back thousands of years, its boom is a relatively recent phenomenon that intersects with the tourism boom. Traditionally, black pigs were considered inextricable from local peoples’ lives, as the pigs ate human wastes, produced natural fertilizers for agriculture, provided protein, and prevented groundwater pollution (Photo 1 and 2). Whereas traditional black pigs are smaller than western pig species, they are more resistant to diseases and thought to have a more desirable food texture.

Photo 1. Traditional Black Pig Cages in Jeju Island. Source: Kevin Sato on flickr.

Photo 2. Traditional Black Pig Cages in Jeju Island. Source: anokarina on flickr.

In the midst of Japanese colonialism in Korea (1910-1945), Japanese settlers interbred black pigs with other domestic and western species to improve their fertility. Even after Japanese colonialism ended in 1945, interbreeding with western species (e.g., Berkshire and Large White) has continued, leading to a reduction in the number of traditional black pigs in Jeju Island. In 1986, the Jeju Provincial Livestock Institute identified five black pigs (male: 1, female: 4) not exposed to interbreeding and introduced protections to ensure their genetic purity. Since then, the Jeju Provincial Livestock Institute has operated a pure breeding system to sustain the stock of pure black pigs on Jeju Island.

Recognizing the unique genetic value of Jeju black pigs, the Cultural Heritage Administration of Korea designated them ‘National Monument no. 550’ in 2015. As of December 2020, the Jeju Provincial Livestock Institute takes care of the designated 348 pigs, distinct from the black pigs raised in conventional farms. Notably, only black pigs raised in the institute’s pigsty are considered to be national monuments. While black pigs produced for market are crossbred to produce more meat, they are not as prized as the leaner national monument pigs. Despite their diminished status, the demand even for crossbred black pigs has dramatically increased with the recent tourism boom in Jeju since the early 2000s. The result has been skyrocketing black pig production facilitated by intensive industrial farming systems.

The Jeju municipal government promoted black pigs as having superior taste due to being raised in the clean environment of the Island. As the Jeju black pigs’ brand marketing became successful, now more than 70 percent of island-produced meat is exported to the Inland of Korea, Japan, and Hong Kong. The tourism and black pig booms, however, place unstainable pressure on the environment of Jeju, especially on groundwater.

Groundwater Issues in Jeju Island: Quality and Quantity

The degradation of groundwater quality is attributed to the illegal discharge of black pig waste into Soom-gols. Some black pig farms in central mountainous areas have discharged excreta into Soom-gols that connect directly to the groundwater. While farm owners should transport their waste to treatment facilities designated by the Jeju municipal government, they let the sludge leak into Soom-gols to reduce the costs of purification, leading to soil contamination and groundwater pollution (Photo 3). As the only source of tap water in Jeju is groundwater, groundwater degradation can threaten public health, as well as the Island’s carefully curated reputation as a pristine tourism destination.

Photo 3. Illegal black pig waste dumping into Soom-gols Source: Jeju Municipal Police.

Some cases of illegal excreta discharge were identified by the Jeju municipal police in 2017 and evoked public indignation. Local residents called for stricter regulations on the disposal of black pig waste, as well as the overall examination of groundwater quality in Jeju Island. According to the research conducted in 2019 by the Jeju Research Institute, the groundwater quality in 2018 showed increased nitrate levels compared to 2014, consistent with contamination from black pig waste. The research also indicates that liquid fertilizers derived from black pig manure pose problems for groundwater. Liquid fertilizers spread over golf courses and agricultural grounds contribute to elevated nitrate concentrations in groundwater.

However, the groundwater issue in Jeju is not a recent phenomenon. According to local newspapers, similar cases have been reported since 1995. Assuming that it requires at least a few decades until surface water arrives in an aquifer and becomes groundwater accessible for human use, the result of the recent groundwater assessment will just be a prelude to more serious groundwater contaminations later on. In other words, even if there is no more illegal discharge from black pig farms, it is hard to imagine that the quality of groundwater will substantially improve soon.

But it is also hard to argue that the sole culprit of the groundwater issue in Jeju is black pig farms’ detrimental practices. A broader perspective implicates additional factors in groundwater degradation. These factors are deeply intertwined with the tourism development in Jeju Island. In 2002, a special law was enacted to deregulate Chinese tourists and Chinese capital investment in Jeju Island. Since then, there has been a number of massive construction projects for building hotels, residences, resorts, golf courses, and other tourist facilities.

Higher tourist traffic, especially in the peak summer season, places greater pressure on groundwater supplies. Such water demand is projected to pick up again after pandemic travel restrictions are lifted. Moreover, as the real estate value of Jeju increased due to Chinese capital investment, Koreans also started to buy more property in Jeju and carry out development without adequate thought for the environment.

Overconsumption has also caused groundwater salination problems. Previously, groundwater pressure was sufficient to resist incoming seawater. However, groundwater pressure dropped due to overextraction, resulting in the contamination of the groundwater and spring water in coastal areas, where the majority of local people reside. To date, such water quality and quantity problems have only been tackled in a piecemeal fashion. The island is at risk of being loved to death until groundwater, black pig farming, and tourism are approached as intersecting concerns.

The Future of Jeju Island

Groundwater problems associated with tourism and black pig booms have garnered growing attention from the local Jeju community. Local people started to actively engage with the issues by participating in environmental NGOs and public demonstrations and by disseminating news through social media. The Jeju municipal government has also recently undertaken several projects to improve and resolve these problems. For example, it constituted a “local peoples’ participatory group for Jeju groundwater” in 2020. Embracing local people and listening to their diverse opinions will be key to the success of these projects and will be a springboard to establishing more robust groundwater governance.

The conflict between groundwater quality and tourism development is not limited to Jeju Island. Popular islands elsewhere, such as the Bay Islands in Honduras and Bali in Indonesia, have also experienced similar symptoms. Clean and abundant groundwater is emblematic of Jeju Island. But the very attributes that make Jeju such a desirable place to live and visit are at risk of disappearing if the tourism and black pig industries continue their trend of unregulated expansion. The ability of future generations to experience the wonder of the Island relies on the decisions made today (photo 4).

Tourism and black pigs will no doubt remain important economic sectors in the future of Jeju. We need to find a middle ground where tourism, black pigs, and groundwater can coexist without compromising the future of Jeju Island. What such a future might look like remains to be seen.

—

Top (feature) image: The beautiful landscape of Jeju Island. Source: Republic of Korea on flickr.