By Daniela Schofield

Notions of climate change adaptation used for policymaking and planning often fail to be grounded in everyday realities of those practicing adaptation on a micro-level. Imbuing urban political ecology with such realities and their gendered dimensions can work to expand our understanding of urban environments and better inform policy and planning.

In late April 2021 Tropical Cyclone Jobo churned across the Indian Ocean on course for Dar es Salaam (Dar), the economic and cultural capital of Tanzania. As Jobo approached, the Tanzania Meteorological Agency predicted that if the cyclone did not decrease in intensity it could yield between 200 to 400 millimeters of rain – up to 30 percent of the country’s annual average of 1,200 millimeters – in just 24 hours. Only six hours from making landfall in Dar, Jobo decreased in intensity sparring the city from its potentially devastating consequences.

While March, April, and May are historically Tanzania’s long rainy season, climate change has shifted weather patterns in recent years. Jobo threatened to deluge the city, and other costal areas, with extreme rainfall in a short period. This highlights the vulnerability of coastal cities, like Dar, to extreme weather events and shines a light on the danger from flooding due to increasingly unpredictable seasonal rains. Increases in the severity of flooding and other climate change related impacts, such as drought and crop failure, have been documented in Tanzania for over a decade. Flooding in Dar has become a fatal reality for its inhabitants, particularly those living in flood-prone low-lying areas.

African cities like Dar are increasingly becoming epicenters where the effects of climate change play out. Dar is likely to reach ‘megacity’ status by 2030 when its population is predicted to be 10 million. It is therefore important that understanding of climate change adaptation is informed by the realities and practices of the individuals and communities living in Dar.

Understandings, or notions, of climate change for policymaking and planning purposes tend to be dominated by technocratic, macro-level, highly masculinized perspectives. These notions fail to take into account the micro-level realities faced by inhabitants of urban areas who are highly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change. This is exemplified by the pervasive gender-blindness in climate change discourse, which tends to be based on a predetermination of gender neutrality. The result is that structural gender and intersectional inequities faced by urban inhabitants are obliterated and not accounted for in policy and planning.

Here, an application of two conceptual frameworks serves to unpack complex intersecting inequities. First, urban political ecology provides a useful framework for examining the unequal power relations within and between urban areas and the differences in exposure to environmental threats faced by these different areas. Yet, the application of urban political ecology has limitations due to its origins in Western theory as well as its narrow focus on cities as spatially fixed units, which often ignores urbanization as a process. Greater inclusion of African urban voices and everyday realities would serve to better situate urban political ecology for analysis of African urban areas. Still, urban political ecology does provide a useful way of understanding how climate change adaptation is sculpted by socio-spatial orders.

The second conceptual framework helpful in the interrogation of urban inequity is the ‘gender-urban-slum interface’ as conceptualized by Chant and McIlwaine (2016). This interface, which draws on feminist geography scholarship, provides a mechanism to analyze gender inequity in urban areas “through a multidimensional, multi-spatial and multiscalar lens.” The multi-spatiality and multidimensionality of such a lens allows for a cross-cutting analysis of urban inequity. Further, the interface’s consideration of multiple scales takes a step toward addressing historical neglect and marginalization of gender in urban policy and planning, particularly in its ability to recognize micro-level activities and everyday realities. Additionally, the inclusion of the term ‘slum’, which the authors acknowledge is contested, allows for a focus on informal spaces.

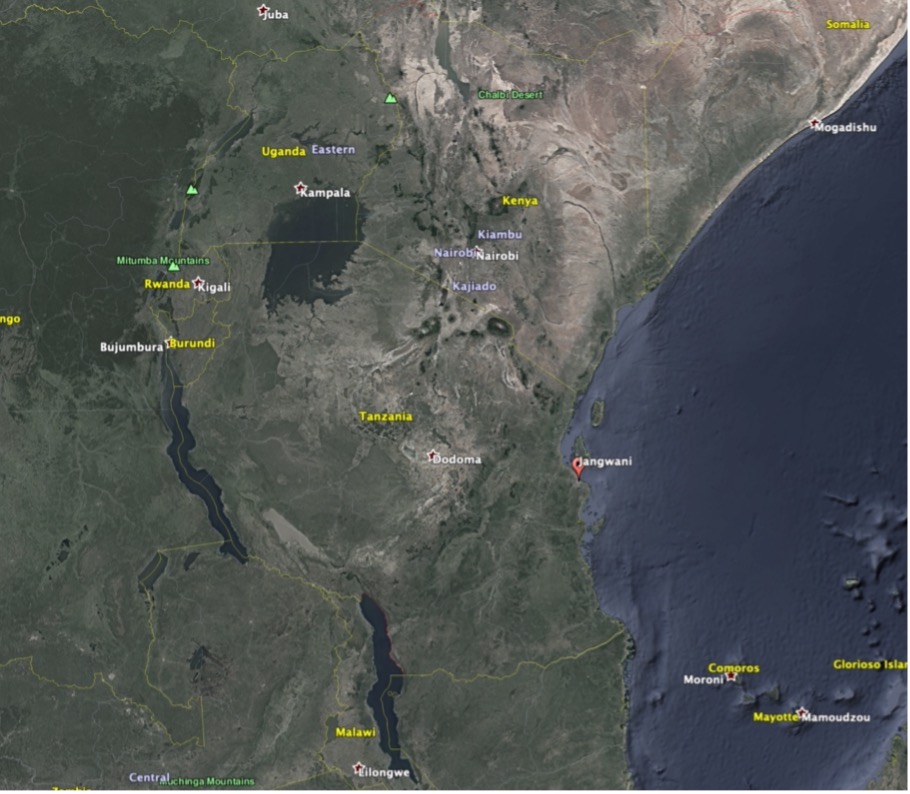

Msimbazi River Basin in Tanzania. Source: Google Earth.

In a 2019 article published in the journal Environment and Urbanization, Femke Gubbels and I explored the gender differentiation present in climate change adaptation in an informal settlement in Dar. Our study was located in Jangwani, a low-lying flood-prone area in the Msimbazi Valley, where the Msimbazi river flows into the Indian Ocean. Jangwani provides proximity to central Dar and most of its residents earn their livelihoods in the ‘informal’ sector — economic activity that is largely precarious, without regulation but also without state backed social protection. The proximity and opportunity to engage in livelihood activities with low(er) barriers to entry makes Jangwani popular among recent arrivals to Dar. At the time of the study (2016) Jangwani was home to about 6,000 people.

Despite these pull factors, there are significant challenges to residing in Jangwani. One of the most prominent is the recurring floods that regularly destroy homes and property. Jangwani, like other areas of Dar, has inherited the legacies of planning inequities which date back to German and British colonial administrations between the late 1800s and the first half of the twentieth century. Colonial planners segregated Dar based on racial lines that privileged non-black races. Although racial segregation was outlawed upon independence in 1961, subsequent planning legislation continued to reflect colonial inequities with wealthier, majority white inhabitants residing in areas with fewer environmental hazards and/or better infrastructure. Additionally, urban planning policy for Dar was largely neglected until the 1980s, and Tanzania’s environmental policy has historically focused on conservation to aid the tourism industry. As a result, Dar’s urban environmental policy is nascent. Addressing climate-related issues is further complicated due to coordination challenges between central and local authorities.

Jangwani was selected as a site of study to provide contextual representation and to unpack homogenized stereotypes of residents of informal areas, which have frequently been referred to as ‘slums’. An informal settlement like Jangwani offers an excellent case study for this. Environmental risks in informal settlements intersect with other system exclusions faced by residents such as gender, poor basic service provision, and racial discrimination. Although ‘informal’ is not always synonymous with ‘low-income’, these barriers to income generation can be higher for residents of informal areas resulting in low-income populations residing in areas of historical deprivation. Thus, environmental risks in informal settlements often compound poverty, increasing the vulnerability of residents to the impacts of climate change.

Rubble and Sand Barrier in Jangwani. Credit: Femke Gubbels, 2016.

Jangwani Residents Shelter in Bus Rapid Transit Shelter. Credit: Ramani Huria and Humanitarian OpenStreetMap, 2015.

Climate change adaptation must not be conceptualized as a practice that happens distinctly from the other areas of everyday life such as housing, transportation, education, livelihood and income-generating activities, and service provision. Examining climate change adaptation on an everyday level helps to understand how adaptations are both interwoven with and interruptive to everyday activities, such as work and education. Residents of Jangwani spoke of needing to leave their houses to stay with a friend or family member or even to take cover in a nearby bus shelter when flooding occurred. Women interviewed spoke of remaining in or staying near Jangwani. They spoke of going to a higher location such as a road or staying with a neighbor whose home was not as badly affected. Men on the other hand reported being able to leave the area altogether, albeit at the cost of having to pay for transport or temporary accommodation elsewhere. Paying to leave was not an option for many of the women interviewed, who spoke of the limitations the faced both in terms of financial means and social networks outside of Jangwani.

Even where actions are taken in order to physically survive the floodwaters, destruction of property was highlighted as a major issue by residents interviewed. One 70-year-old resident reported her house flooding regularly and that although she can stay elsewhere “almost everything in the house will be taken by the water.” Other residents attempted to stave off floodwaters by constructing rubble barriers in front of their houses. These micro-level adaptive actions are conducted out of necessity as local, national, and international policy-making processes lumber slowly along.

By drawing on the views and lived experiences of Jangwani residents, gained through semi-structured interviews, we exemplify how the perspectives and experiences of individuals and communities grappling with climate change can be included in urban scholarship. Doing so allows us to challenge the notion that residents of informal areas are homogeneous. It also works to progress understandings of urban environments from reductionist political economy analyses. Our aim in doing so is to ensure that the study of climate change does not stop at solely being the examination of environmental occurrences, but one that includes consideration of the political, economic, and social forces driving spatial injustice in urban areas.

Of course, our examination is far from representative of all urban settings globally, throughout Africa, or even across Tanzania. Yet, it provides a useful case study that helps to illustrate the differences between adaptive activities of men and women in Jangwani as well as the importance of the consideration of age differences between residents. In doing so, this study draws on urban political ecology and the gender-urban-slum interface to lay the groundwork for additional research that can continue to disassemble the homogenous conceptualization of informal inhabitants and their responses to climate change.

Our application of the gender-urban-slum interfaces helps to infuse urban political ecology with greater considerations of gender. Beyond this study, I hope that the joint application of urban political ecology and the gender-urban-slum interface serves two purposes. Firstly, to work toward greater inclusion of gender considerations, and making such considerations more predominant, in urban ecological scholarship and subsequent policy making. Secondly, that those using urban political ecology as an analytical framework continue to seek to imbue such analyses with other interrogative critical frameworks. Doing so will allow for examinations of overlooked urban experiences and expand the theoretical basis from which we draw to understand urban environments.

Daniela Schofield is a researcher with interests in gender and informality in urban areas, particularly in East Africa. You can learn more about her research at danielaschofield.com or follow her on Twitter @DaniSchofield.