By Linda Estelí Méndez Barrientos

The climate justice movement needs to move from protest to action. This includes mobilizing to support communities in the Global South as they strive to juggle their recurrent climate emergencies.

On November 16th, hurricane Iota hit the Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua as a category 4 storm with winds of 155 mph. Just 13 days earlier, another category 4 hurricane named Eta landed in the same spot only 15 miles away. Early estimates indicate that the impact of Eta alone may be equivalent to around one fifth of the affected Central American countries’ gross domestic product (GDP). At risk of catalyzing a new wave of “white saviors” coming to the Global South to support humanitarian efforts, the reality is that activists in the Global North need to learn how to support local activists to adequately connect movements and expand participation across the Global South. Climate justice means we need more than protesting and lobbying politicians for climate action.

People seeking refuge under an overpass in San Pedro Sula, Honduras. Source: Seth Sidney Berry/SOPA Images/REX/Shutterstock

Scientists agree we may now be well beyond the turning point to avert climate change related catastrophes. This means that the impacts of global warming will continue to be felt across the globe disproportionately, especially in the Global South were the majority of the impacts are expected. Events of the past several weeks give a strong indication of this inequality. From what have become constant heat waves and wildfires across the Western United States, to unprecedented typhoons in the Philippines, to record-breaking hurricanes in Central America, the climate emergency has become more tangible than ever before. The impacts of climate change know no borders and are especially felt in the Global South.

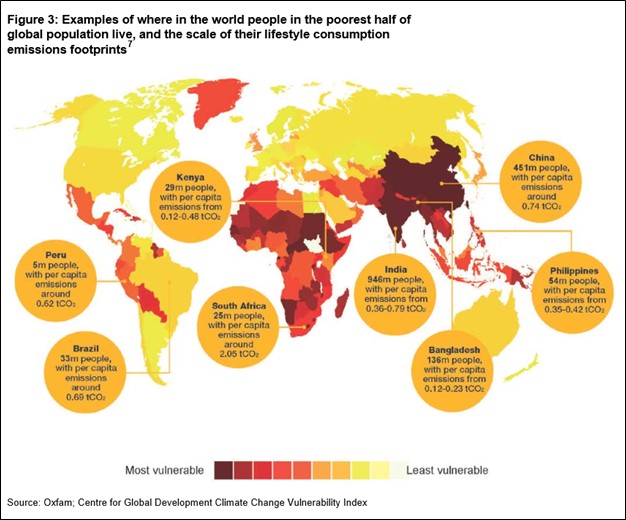

Stark inequality and economic disparities not just across the North-South divide but also within different communities in the South further exacerbate climate impacts. The poor and disenfranchised are always hit the hardest. The irony is that while the world’s richest 10% are responsible for as many emissions as the bottom 90% combined, they are less vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Meanwhile, environmentalists keep dwelling in outdated debates focused on population control, ecosystem’s carrying capacities, technological fixes, and market-based solutions that continue to perpetuate unequal power relations, white supremacy, and the heritage of (neo)colonialism. Importantly, these approaches are not getting the job done.

Climate Change Vulnerability Index. Source: Oxfam.

We need to urgently move beyond these distractions that deter progress in adequately addressing climate change and its impacts. Instead, climate justice movements need to grow from fragmented movement-building concentrated in the Global North towards global community integration. For example, the Degrowth movement in Europe, the Sunrise Movement in the United States, and the international Fridays for Future movement have exponentially grown to new geographic areas, adding local “hubs” or chapters in various states and countries. Unfortunately, this geographic expansion has yet to be matched with an integration of a plurality of peoples, priorities, and strategies. Bluntly, how are children and youth who do not have access to education able to join a weekly global strike for climate change? They just don’t.

Connecting existing and interdependent local climate justice initiatives and organizations to mobilize solidarity networks that support advocacy efforts in the Global South is crucial. Moreover, movements need to support resiliency in the face of recurrent devastating climate catastrophes that continue to erode social, economic, and political resources in the Global South. Striking a balance between the medium to long-term efforts to transform global environmental governance systems with the urgent short-term needs of people fighting for basic human and nature rights is key. This is especially important given that global environmental policies remain focused on the protection of the environment and not on simultaneously increasing social justice.

National protest for the protection of water access in Quito, Ecuador. Source: Rachel Conrad, Acción Ecológica, Ecuador.

How to move towards a decolonial and anti-racist climate justice movement

A decolonial and anti-racist approach to movement building would introspectively assess the heterogeneity of parties involved in and excluded from current climate justice efforts. Furthermore, it would engage local activists and existing organizations by prioritizing their chosen and decentralized local needs, while simultaneously building and reinforcing these social networks to create broad climate justice coalitions. It would also acknowledge that power struggles are not absent in social organizing. Therefore, it would keep in mind that a movement that builds on the interventions of non-state actors and various organizations at multiple levels would inherently run the risks of local elite capture, especially in highly inequitable societies. Appropriate solutions would thus not only address people’s concerns: by including more diverse values and priorities of affected people, it would facilitate a space to contest and influence what is defined as urgent.

Hence, solidarity in the climate justice movement would demand:

- Centering equity as a co-equal goal to environmental sustainability

- Evaluating inclusion and representation to ensure procedural and distributive equity

- Supporting policies that do not disproportionally affect the disadvantaged and on the contrary, invest in the protection and promotion of their rights and priorities

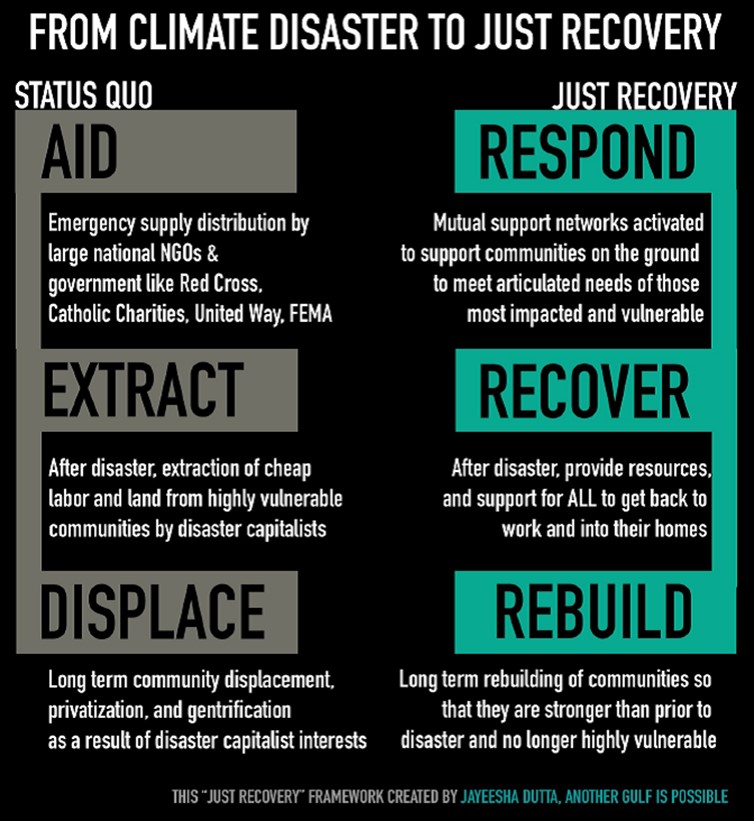

A concrete example of a movement working to address these gaps is the work of the Climate Justice Alliance. They have embraced a just recovery framework inspired by grassroots activist work after hurricanes Harvey in the Gulf of Mexico and Maria in Puerto Rico. Their proposal centers response, recovery, and rebuilding efforts on those most impacted and vulnerable by climate change catastrophes. This represents a shift from disaster relief efforts, which historically and continually focus on short-term emergency aid, reliance on extractive economies including cheap labor, and the capitalization of disasters as a means of displacement.

Just recovery framework from the Climate Justice Alliance. Source: CJA.

With these three principles in mind, a global climate justice movement could empower communities against the disproportional impacts of climate change, while continue to play a strong advocacy role that shapes public opinion and therefore policy. In parallel and despite on-going divisive debates among academics and activists in the Global North, a genuine grassroots climate justice movement would move beyond protest and towards solidarity, acknowledging local concerns, voices, and knowledges.

—

Linda Estelí Méndez Barrientosis a human ecologist and environmental policy scholar at the University of California Davis. Her work focuses on power asymmetries and institutional change in the design and implementation of sustainability reforms. She is the founder of S2E-Science to Empower, an initiative that facilitates applied science to support the defense of human and nature rights.

Profile picture: Climate justice march in New York City. Source: Climate Justice Alliance.

One Comment