By Lisa Bossenbroek, Hind Ftouhi, Abir Benfars and Nawal Taaime

How do small-scale farmers and agricultural laborers in the Draa Valley, in the South-East of Morocco, experience and respond to the Covid19 crisis? Their experiences illustrate how the crisis tests their resilience and expose the vulnerability and the limited resources some rural actors have to deal with crises.

“This year has been particularly difficult especially for farmers who don’t have a well. They suffer from a lack of rain and on top of that from the Covid crisis”, explains Hamid, a farmer in the oasis of Ktaoua in the Draa valley, South-East of Morocco. The country’s agricultural sector is a central pillar of the national economy. Yet, it faces severe challenges related to the Covid19 crisis and the resultant lockdown. From mid-March until July, the country has maintained a severe lockdown with regional and international travel restrictions. Farmers’ markets have been closed, transportation and movements have been limited, and farming inputs were difficult to obtain. Since then, several national restrictions have been lifted and are now organized at the regional level, hampering the mobility between regions, while the threat of a total lockdown is looming. These factors have added new challenges to farmers who are already dealing with climate change, water scarcity, and salinity. Yet, little is known about how small-scale farmers experience these changes and deal with the challenges related to the pandemic.

As part of the SalidraaJuJ project and the DUPC2-Water-intensive agricultural growth in the Maghreb project which focus on the Draa valley, we interviewed farmers to better understand how they experience and cope with the unfolding Covid19 crisis. After illustrating the importance of the agricultural sector in the Moroccan context and the Covid19 related actions taken by the government, we zoom in on the lived-experiences of small-scale farmers producing watermelons. They farm on collective lands, situated around the oases, and depend on groundwater for irrigating their crops. Although the production of watermelons in an arid environment is part of a very heated societal and scientific discussion, our research rather focuses on the experiences of these small-scale young watermelon farmers in times of the pandemic. Then, we highlight the experiences of agricultural laborers and continue by presenting the experiences of subsistence farmers who farm inside the oasis and who depend on water released from the up-stream located dam to irrigate their lands, sometimes in combination with private wells.

An elderly man in the oasis of Mezguita irrigating his fodder crops. Photo: Lisa Bossenbroek.

Morocco’s agrarian political economy and Covid19 response

In Morocco, the agricultural sector occupies a predominant role in the national economy. It counts for 13% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), 38% of the employment at the national level and around 74% in rural areas. The latter number may even be higher as it is not clear if it covers workers of the informal sector, who often work without a contract, social security, and medical coverage.

In 2008, the Moroccan government launched the Plan Maroc Vert. Through targeted efforts to increase productivity and efficiency, the plan puts the agricultural sector at the heart of the national economy. It stands on two pillars. The first pillar consists of the development of a modern, intensive, and competitive agricultural sector, based on high-value crops, new technologies, and intensive inputs. The second pillar – solidary support – is aimed at assisting the small and medium-scale farmers in their farming projects. Critical analyses of this policy reveal that the first pillar is strongly favored and reinforces a dualist agrarian sector. Nevertheless, as part of the second pillar, significant investments have been made to improve the livelihoods of the rural poor. These include, among others, the establishment of agricultural cooperatives, subsidies for agricultural equipment (for example drip irrigation, water basins, different types of crops), and the promotion of local products. In early 2020, the Green Morocco Plan was substituted by a newly designed plan “Generation Green”. The precise outline of this plan and how it will be put into practice remains so far unclear.

With the arrival of the Covid19 pandemic, the national government launched several initiatives to support the vulnerable populations affected. Since healthcare is not accessible for a large part of the (rural) population, such initiatives have become important for families and individuals to survive. One such initiative is the “Tadamon” (solidarity in Arabic) program, which provides aid for several categories of vulnerable groups. Additionally, other forms of aid given by the state or non-state actors exist, but they are not related to the Covid19 crisis. One such example is the Ramadan basket funded by the Mohamed V Foundation for Solidarity, which consists of basic food products distributed to vulnerable households during the Ramadan period. These different initiatives nevertheless do not specifically target the rural population.

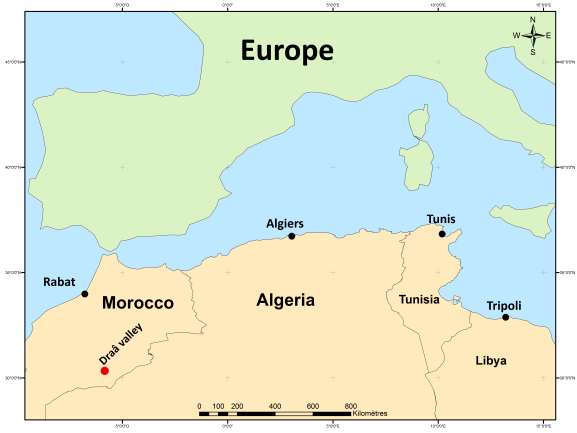

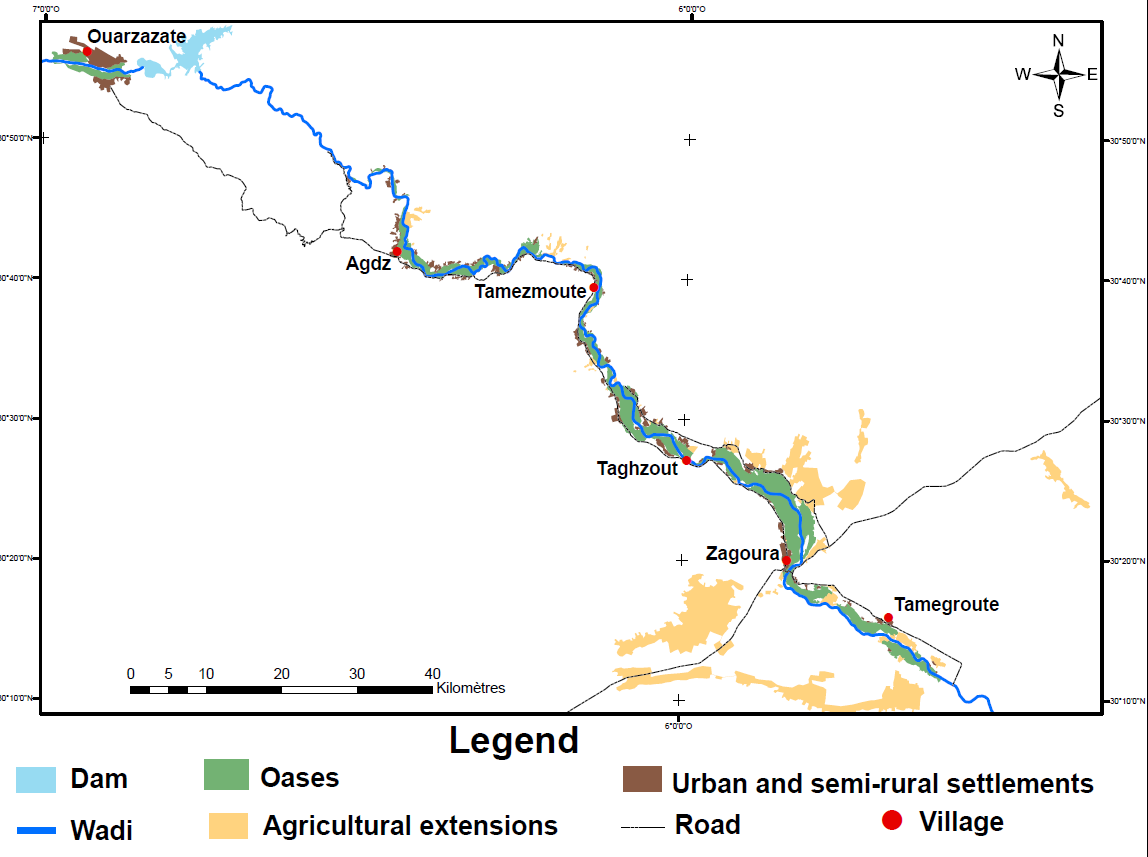

Location of the Draa Valley and the different oases. Maps: Farah Hamamouche

The Draa valley: oasis subsistence farming and newly emerging farming practices

The Draa valley is characterized by a belt of ±200 km consisting of six oases, which provide a green stripe of palm trees in a desert environment. The main water source for the oases comes from the High Atlas Mountains and is stored in the El Mansour Eddahbi dam near the city of Ouarzazate, which was built in 1972. Initially, between four and eight dam releases were planned yearly. Today, depending on the water availability water is released four times a year. Each dam release is between 30 and 40 million m3 (Ibidem) and serves the 6 oases. To deal with the water deficit, farmers throughout the valley have dug wells. Yet, not all farming families have the financial possibility to dig wells and over the years some wells have dried up. Besides, downstream groundwater is increasingly saline, which affects the agricultural production. In the oases, subsistence (irrigated) farming is essential for fulfilling the livelihoods of small-scale farming families. In addition, over the last decade, new types of crops (like watermelons) foremost aimed for the national and international markets, are increasingly cultivated on so-called extensions: rangelands located outside the traditional oases. These new farm practices fully rely on groundwater access and control. Originally, these lands were used for grazing purposes and are owned by local tribes.

Multiple crises faced by young watermelons farmers

The young watermelon farmers who we interviewed farm on tribal-owned lands located outside the traditional oases. They belong to the local tribes to whom these lands belong. They are small-scale farmers and combine, on a couple of hectares, the production of watermelons with the production of vegetables, foremost used for family consumption. This farm model distinguishes itself from the large watermelon farms extending on tens of hectares, managed by farmer entrepreneurs who are often not from the area and who mostly engage in mono-cropping farming practices. This year the harvest of the watermelons began in early April, only weeks after the lockdown began. Since the production of watermelons requires significant investments in terms of fertilizers, seeds, and agricultural material, it’s common to take loans at the beginning of the cropping season. When the lockdown was announced the young farmers started to worry that they would not be able to commercialize their crops and pay back their loans, as the testimony of Hamid[1] illustrates:

“When on the 20th of March the lockdown was implemented we thought it would last for a month until the 20th of April. We, therefore, didn’t foresee any problems since the production would only be ready around the 25th of April. Yet, when the government announced the extension of the lockdown, we started to worry about how to sell our products and reimburse our credits…”.

Harvested watermelons in the Feija plain during the lockdown. Photo: Hmad, a local farmer.

The watermelon economy strongly depends on national intermediaries and buyers who travel to the region during the harvest period. Due to the transport and mobility constraints, and the excessive administrative proceedings, only a few buyers and intermediaries were able to travel to the area. Consequently, the young farmers faced difficulties to sell their harvest, as Ahmed indicates:

“There are only a few buyers and they install a monopoly. They decide on the price, there are no other alternatives. Before when there were more buyers we were able to negotiate prices…”.

Additionally, the buyers usually select the best watermelons and leave the rest. This is particularly the case when they are for export. In normal times, the watermelons of less quality are sold throughout the region. Yet, this year, the souks (weekly local markets) were closed due to the lockdown, preventing their sale. Moreover, because of the mobility restrictions, young farmers faced difficulties bringing their products to nearby cities and smaller towns. As a consequence, the watermelons of poorer quality were left on the fields to rot or were given to livestock animals.

It’s however not the first crisis that the young watermelon farmers experience. 2018, for example, was for many a disastrous year. As a young farmer explained, “many farmers ended up with high debts”. This was due to the high production of watermelons compared to the low demand: the market volatility of watermelons in the region is very high. Ahmed, a former farmer who works for three years in the tourist sector explains: “The cultivation of watermelon is like the lottery (9mar), there is no guarantee… Today, the price of watermelons has drastically dropped.” Because of the low prices, in 2018, some farmers let the watermelons rot in the field and decided to minimize their expenses in the following years by reducing the number of agricultural inputs used and reusing their water drip lines and plastic mulch, used to warm the soil, retain the moisture and prevent certain diseases. Others planted watermelons on a smaller area and diversified their crops, as Said tells:

“… sometimes I cultivate four hectares, sometimes three [of watermelon], and plant on the remaining hectare some pineapple and another variety of melons”.

Last years’ experiences remain engraved in the young farmer’s memories and with the Covid19 related sanitary measures imposed by the state, they expected worse this year. They “fought a lot”, and managed to sell at least part of their products as a young farmer explained: “The situation could have been worse (hal hssen men hal). Even if the current price is low, at least the watermelons didn’t end up rotting on the fields and were sold. That’s the most important. Only a few are left, just the ones of lower quality…”.

Although most farmers made little or no profit this year, the majority didn’t find themselves with additional debts. As such, market volatility, but also common knowledge of farming practices shared on farmers’ whatsapp groups, and the fact that they are from farming families from the area and already have some farming experiences, contributed to the resilience of these young watermelon farmers. Through the coping strategies they developed during the last couple of years they were able to deal with the Covid19 crisis.

High wages and the Moquef (labor market) on Whatsapp

The harvest of watermelons relies on a regional workforce, with laborers (foremost men) coming from other regions in Morocco and from the cities in the valley. Yet, the mobility restrictions enforced during the harvest period led to a severe labor shortage; this, in turn, led to higher wages.

Normally, laborers are recruited in the moquefs: these are places usually situated at the outskirts of small cities in the valley, where wage workers gather in order to find a job for the day. Yet, as the moquefs throughout the region were banned, the recruitment of laborers was organized locally and through social media, such as farmers’ Whatsapp and Facebook groups. In case laborers didn’t have access to social media they were informed by phone or by neighbors about labor opportunities. Others, who live in surrounding villages and weren’t able to obtain mobility permits delivered by the authorities, took dirt roads to avoid police stops to get to the farmers’ fields. Once the workers started to work on the land of one farmer, they moved collectively to the field of the next farmer, until all the fields were harvested. These alternative recruiting strategies helped address the labour shortages, though they mostly benefited local laborers, and not the ones from surrounding cities or other regions.

Subsistence farmers in the traditional oasis: suffering from prolonged drought and the pandemic

While young watermelon farmers cope the way they can, in the oases, where agricultural activities heavily rely on the water released from the El Mansour Eddahbi dam, the situation is quite different. The impact of the pandemic is amplified by a year of drought due to the lack of rainfall upstream, and by saline water downstream. Landless farmers, and small-scale farmers who combine farming activities in the oases with work in the watermelons farms, can no longer do so because of the mobility restrictions, and the oases offer few alternative employment opportunities. The tourist sector, for instance, is now at a standstill, and those who used to work there to diversify their income, are turning to government assistance. For others, such as female-headed households, it is difficult to benefit from governmental support programs since husbands, absent because of temporary migration, illness, or other, are still considered as the head of the household. For these households, financial support from migrated family members has become the only source of income.

In some oases, such as Fezouata, the pandemic has mainly affected the marketing of dates, a product that plays a central role in the oasis’ economy. Once the dates are harvested around October/November, they are usually stored and sold at a higher price during the month of Ramadan, which started this year on the 24th of April and lasted until 24th of May. But the pandemic’s restrictions contributed to reduced selling opportunities and few if any benefits.

The pandemic not only affects economic activities, but also the fragile autonomy of some rural actors which took years to build. The experience of Khadija who is divorced, illustrates this well. She is a member of a women’s agricultural cooperative in the region, specialized in bread production. For many rural women, such cooperatives are important in terms of personal development and some degree of economic autonomy. In rural Morocco, women are traditionally confined to the private sphere and are foremost in charge of domestic chores and (unpaid) agricultural work. Cooperatives provide another (legitimate) space for women to gather outside the private sphere, and provide modest economic support. In the case of Khadija, the cooperative “helped a lot” and gave her “importance and a new identity”. During normal times, the members sold between 100 and 200 loaves of bread a day. For weddings and funerals, they could sell up to 600 loaves of bread a day. But this year, the sale hardly exceeded 20 loaves of bread a day. Some members of the cooperative benefited from individual aid from the COVID-19 fund or the Ramadan basket, but today the future of the cooperative is uncertain, and sometimes, as Khadija mentions “we lose all hope”.

Agricultural fields equipped with drip irrigation in the plain of Feija, located outside the traditional oases. Photo: Hind Ftouhi.

Conclusion

Shall we indeed lose all hope? Or are there other answers to cope with this current crisis? What can we learn from the different ways of how rural actors experience and cope with the situation? As the different experiences in this article illustrate, the Covid19 related crisis is a revealing period. It’s a moment to reflect on and learn from local experiences and their ingenuity. Although young farmers struggled to sell their products their adaptation strategies are inspiring. Not only do they contribute to reducing costs, but are perhaps at the same time less harmful for the environment and human health. Also, to harvest the land, new forms of local connections among laborers and arrangements of mutual aid among farmers are forged. At the same time, the lockdown, linked mobility restrictions, and newly emerging local recruitment networks make it difficult for workers outside the region to join.

On the other hand, the unfolding crisis tests the resilience of rural populations and exposes their vulnerability and the limited recourse some rural actors sometimes have to deal with crises. For example, for farming families in the oasis, the Covid19 related impacts add to challenges already at play due to droughts and poor water quality. Here it is important to look at the diversity of experiences, as some may be more affected than others. In this regard, landless farmers, farmers who only depend on the water releases from the dam and don’t have additional wells, and de facto female-headed households, to name a few, may be further marginalized as a result of multiple challenges. It is crucial to make their voices heard and to understand their needs in order not to further exacerbate the growing social and economic inequalities in a rural world suffering from the pandemic.

—

Lisa Bossenbroek is a researcher at iES Landau, Institute for Environmental Sciences, University of Koblenz-Landau, Germany, where she is co-leading the project SALIDRAA 2 – Salt in the system, which focuses on the social and environmental impacts of salinization in the Draa River Basin in Morocco. She is member of the projects “T2GS: Transformations to Groundwater Sustainability”, “DUPC2-Water-intensive agricultural growth in the Maghreb” and “Farming in times of crises: experiences, responses and needs of smallholder farmers during the COVID19 pandemic”.

Hind Ftouhi is a researcher in rural sociology and the local project leader of the project “Farming in times of crises: experiences, responses and needs of smallholder farmers during the Covid-19 pandemic” and member of the projects “T2SGS: Transformations to Groundwater Sustainability” and DUPC2-Water-intensive agricultural growth in the Maghreb.

Abir Benfars holds a Master in Water, Energy and Environmental Sciences from l’Ecole Normale Supérieure de l’Enseignement Supérieure, Rabat.

Nawal Taaime is an agricultural engineer at the National School of Agriculture, Meknes.

—

Acknowledgements:

For this research we gratefully thank the Germany Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) for financial support in the framework SALIDRAAjuj-01UU19, DUPC – IHE Delft and the T2GS Project.