By Pablo Domínguez, Maja Kostić-Mandić and Milan Sekulović

The “Save Sinjajevina” initiative is mobilizing to defend the Sinjajevina-Durmitor massif mountain range, a traditional pastoral territory in Montenegro, from being converted into a military training ground.

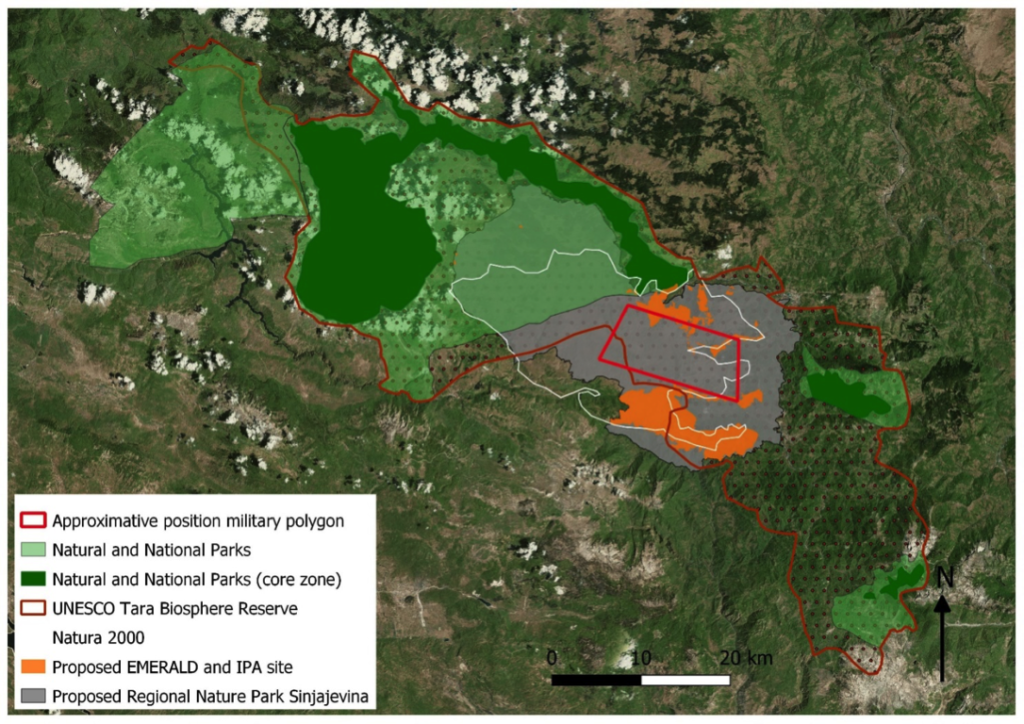

There is a crisis brewing in the Sinjajevina-Durmitor massif mountain range in Montenegro where a substantial part of this traditional pastoral territory is being converted into a military training ground. The mountain range is composed of a limestone plateau of over 1,000 km², mostly between 1,600 to 2,200 meters above sea level, making it the second largest mountain pasture in Europe. The area of Sinjajevina covers 600 km² in the southeastern part of the massif and its natural and cultural values are widely recognized. Importantly, it is situated at the heart of the Tara Canyon Biosphere Reserve, and has two UNESCO World Heritage sites at its northern border (see map below).

The military installation has carved out a huge chunk of land from the proposed Regional Nature park in Sinjajevina. Source: Johann Blanpied & Pablo Dominguez

Pressures on a tradition of harmony with nature

Sinjajevina’s rich bio-cultural diversity is a symbol of symbiosis between nature and society, a product as well as the heritage of local pastoralist communities’ governance and management over centuries. About 22,000 people live in Sinjajevina’s lower lands today, and more than 250 pastoralist families from eight different Montenegrin tribes use its highland pastures, of which many are still collectively governed by different communities (katuns) through assemblies of users (traditionally named zbor). Therefore, Sinjajevina could be considered to be a cluster of pastoral commons or community-conserved areas, as defined by the ICCA Consortium. The area is connected with a large part of Montenegro through transhumance, the ancient practice of moving grazing animals between two complementary places: in this case, from the lower valleys in winter, to the highland pastures in summer, an annual cycle which has repeated itself over the last one thousand years. This practice effectively makes Sinjajevina’s social extent much greater than the strict limits of its territory.

The European Union has recognized the environmental significance of the Sijajevina pastureland. Source: Sandra Kapetanovic & Pablo Dominguez

In April 2018, an extensive study largely sponsored by the European Union recommended that Sinjajevina be declared a Regional Park for the protection of culture and nature, as well as for the enhancement of local economies. The local people expected action on this within eighteen months of the finalization of the report. Instead, on the 27th of September 2019 the Montenegrin government officially inaugurated a military polygon, over 7,500 hectares in size in the very heart of Sinjajevina. (The exact area and its limits are still not clear). In a bizarre turn of events, Montenegrin, American, Austrian, Slovenian and Italian troops engaged in the first international NATO military training that day, shooting and throwing smoke bombs while shepherds were still present in the area with their flocks. The appropriation of this land took place with no publicly available environmental, health, or economic impact evaluations, and without any substantial negotiations with the affected pastoral communities, or any apparent respect for their legal rights.

Military top brass observing the army exercises in Sinjajevina. Pic. – Dragana Scapenovic

Armaments on display at the first international NATO military training in Sinjajevina. Pic. – Dragana Scapenovic

Resisting a “development” onslaught

Given what is at stake for their livelihood as well as for their environment, the people of Sinjajevina have strongly opposed the installation of a military training ground on their pasturelands. The “Save Sinjajevina” initiative was informally started in March 2018, soon after the first news reports of the government’s military move appeared locally. Environmental movements in Montenegro have been quite strong and unwavering, and the founders of the “Save Sinjajevina” initiative built on the previously established collaborations with other local activists, primarily the residents of the village of Bukovica (below Sinjajevina) who had successfully defended their river from a mini hydropower plant recently, and the residents of Zabljak who opposed the devastation of the National Park of Durmitor. This further led to connections with other environmental organizations and individual activists around Montenegro, which ended up with the formation of the Coalition for Sustainable Development (KOR) in August 2019, today the most important environmentalist federation in the country.

The local activists have challenged the onslaught on their pastureland. Pic. – Nikola Lucić

Local activism against the proposed military project was built around a dynamic effort to influence the debate through protests, signature based petitions and outreach to a network of civil society groups, both, nationally and world-wide. Some residents of Sinjajevina also took an active part in a public debate with the Ministry of the Defense and the Army’s ranks that took place on May 15th 2018 in Kolašin. They asserted that the debate had been primarily organized on the initiative and in favor of those who wanted to build the military training ground, and demanded a true and openly public referendum on the issue, which, unfortunately, was never granted. In an impassioned demonstration of their commitment to saving the pastureland, the people said that they would not allow the army to make a Chernobyl out of Sinjajevina, and, if necessary, they would defend the katuns and the pasturelands with their lives because, in their words, they could not go to live somewhere else “naked and barefooted”. The local communities also alerted the military and civil administrators of the immense risk of pollution transmission to the two extremely important rivers of Moraca and Tara if the project went ahead, and how that could make the mountains unsafe for both tourists and locals.

Activists gathering for a demonstration against the military installation. Pic. – Mićo Baltić

In summer, last year, when it became clear that the administration was unwilling to reconsider its continued engagement with the project, the Sinjajivena activists also organized a rapid response signature campaign against the military encampment under the banner of the newly formed “Save Sinjajivena” association. Even though the petition garnered support from more than 3000 people, a requirement needed for the Montenegrin Parliament to accept an issue for debate and give its considered decision on it, the petition was embarrassingly ignored, both, by the Government and the Parliament.

Building solidarity

The “Save Sinjajevina” movement has been conscious of its ideological imperative since the start, and has projected a civil, transnational and pro-European stand along with an abiding respect for human rights and local communities. While it accepts support from like-minded actors, the “Save Sinjajeviaa” movement does not, however, profess to have an affiliation with any political party. The movement has ventured to explore alternative forms of environmental resistance to protect nature, and the right of the people to live in harmony with it, through activism on the ground and by building networks, which strengthen its activities. This has brought “Save Sinjajevina” in the crosshairs of the ruling party, which has begun treating its members as enemies of the State or even external agents linked to the Serbian secret service, going to the extent of accusing them of being anti-NATO and pro-Russia. The allegations are, obviously, absolutely groundless, and this tactic simply exposes the government’s need for an imaginary external enemy to justify its internal policy and legislation. The movement, in fact, is being supported by a large number of people who vote for the ruling party and some who even belong to its ranks, but are against the destruction of their fragile ecosystem and cultural traditions, and the attempt by people, both, inside and outside the government to profit from that.

A folk festival coming alive in Sinjajevina. Pic. – Nikola Lucić

“Save Sinjajevina” has rooted its initiatives in the conviction that civil society has the power to strengthen democracy through social participation. They have done so by repeatedly contesting the process by which Sinjajevina was declared a military training ground in a patently undemocratic manner. It’s instructive to bear in mind that as yet there is no official document from the government explaining why a training ground is needed on a traditional pastureland and what real impact it would have on the larger ecology as well the economy. Instead, what the people have been handed is a vague assurance from the Minister of Defense that “everything will be fine”… The wider public opinion in Montenegro has, however, begun to challenge the apathy and the indiscretion of the government, and the grassroots movement in Sinjajevina has received broad support from opposition parties in Montenegro.

The international outreach

The “United Reform Action” (URA), a progressive and socially liberal political group has been quite proactive in backing the cause of “Save Sinjajevina”. Its affiliation with the European Green Party and the growing work of concerned and informed academics has contributed to the pastureland issue being afforded visibility and concern at the European Parliament. Earlier this year, in February, members of the European Parliament (including the Chair of the EU Delegation, Vladimir Bilcik of the Christian Democrats, and the co-chair of the European Greens, Thomas Waitz) visited Montenegro as part of the European Parliamentary Committee for Stabilization and Association of the European Union and Montenegro after they had been contacted by the “Save Sinjajevina” activists. The delegation issued a declaration expressing particular concern about Sinjajevina, advising that: “Utmost caution is called for in UNESCO-protected areas, including the Tara River and the Sinjajevina mountain area, where in September 2019 a military training and weapons testing area was established within the UNESCO Biosphere Reserve”. It also emphasized the importance of “preserving the cultural and pastoral traditions of local communities”. The EU delegation further underlined “the need for an independent study of the social and environmental impacts of the military landfill in Sinjajevina”. The Montenegrin government has decided to ignore this recommendation along with the EU advice on protecting the Sinjajevina pasturelands, which only isolates Montenegro from EU standards and international policies even further.

In Sinjajevina socio-economic existence has evolved in harmony with the mountains. Pic.- Nikola Lucić

The ethno-political conundrum

Unfortunate, as it is, the path to an ecologically sustainable and economically meaningful solution to the Sinjajevina crisis passes through the thorny domain of national politics in Montenegro. But, as it is always in the Balkans, the perplexing nature of the country’s ethnic and religious equations makes it even more tortuous and unpredictable. Broadly speaking Montenegro, today, is caught between two growing right-wing nationalistic political discourses – the first has been shaped by the autocratic vision of Milo Dukanovic, the long time leader of the country and whose personal story is enmeshed in the events that led to the emergence of Montenegro as an independent country. The second formation is led by a group of socio-cultural and political forces that owe allegiance to the Serbian, Russian and eastern Slavic identity.

Dukanovic emerged on the political scene at the time of the anti-bureaucratic revolution in Yugoslavia as a close ally of the Serbian autocrat, Slobodan Milošević in the 1990s. An international tribunal had charged Milošević for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes but he died in prison before the case could be completed. Dukanovic turned against Milošević in 1996, and also started abandoning the traditional, centuries old, Serbian-Montenegrin ethnic and cultural bond, ultimately achieving independence in a referendum in 2006. Dukanovic had a well thought out plan for his country as well as himself. Over the course of his premiership and presidency, Dukanovic eagerly bought into the neoliberal agenda of the west, and undertook massive privatization of the country’s public companies. He offered easy terms of ownership and engagement to foreign investors and firms from whom he and his close allies never ceased to benefit. Dukanovic’s rule has been marked by a high degree of kleptocracy resulting in allegations of personal profiteering, which has provoked a series of peaceful protests in the course of the last decade. An Italian tribunal accused Dukanovic of collaborating with the mafia, but that case had to be dismissed when he acquired immunity due to his status as the head of the state.

The Montenegrin ruling elite have worked to create a pseudo self-image of being the first line of defense against a Russian push into Western Europe, together with Serbia.

The pastureland and the politics of cynicism

Milo Dukanovic has fabricated an identity for himself and his country as a bulwark against the westward push of the Russian state in Europe in partnership with Serbia. That’s also one of the reasons why the conversion of the Sinjajevina pasturelands into a military installation is of crucial importance to him – to display and underline his seriousness about being a reliable ally to NATO and Western Europe. The story, however, gets complicated because of the way the balance of socio-political power is unfolding in Montenegro. Sinjajevina is in the northern part of Montenegro, close to Serbia, and is composed of traditional populations, with Serbian socio-cultural affinities and whose affiliation with the pro-Serbian opposition is discernible. In fact, an important part of the opposition has embraced the movement in support of the pastureland so as to protect a consequential Serbian geo-symbol and population within Montenegro, and, in the process, advance its own Serbian nationalist agenda. As the country prepares to hold the next parliamentary elections at the end of August, there is a risk that Serbian nationalism could try to appropriate for itself the environmentalist movement around Sinjajevina. It’s possible that a turnover in power at the national level could circumstantially protect Sinjajevina from the current, most imminent threat (i.e. the installation of the military base), but such parties would not be able to provide a systemic approach to environmental justice and socio-environmental sustenance in Montenegro, because the logic of their involvement is not based in scientifically sound or economically egalitarian reasoning. Their agenda of nationalism would prevail over almost everything else.

Sijajevina represents an enduring relationship between humans and nature. Pic. – Mićo Baltić

Looking to the future

“Save Sinjajevina” is not a pro-Serbian organization even if the most important part of the affected populations self-identify as Serbs. It defends a highly transversal socio-political cause, that of social justice and the rights to Nature. The movement respects humans in nature. As for the entity called the nation, it merely represents the place where nature exists. Currently, the two rival nationalist forces in Montenegro are light years away from the twenty first century visions of the state’s role in protecting nature and its citizens within the larger framework of democracy. As it advances an alternative form of local resistance to state and a false notion of “development”, the “Save Sinjajevina” movement hopes to contribute to forging a meaningful path towards a progressive environmental future for Montenegro, and the reformulation of the democratic process in the country.

Pablo Domínguez is at CNRS (Laboratoire de Géographie de l’Environnement), France and associated with the Autonomous University of Barcelona (Social and Cultural Anthropology Department (ASiC) / Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals), Spain.

Maja Kostić-Mandić is at the University of Montenegro (Faculty of Law).

Milan Sekulović is the Secretary General of the “Save Sinjajevina” civic initiative.

Resources on the “Save Sinjajevina” initiative

- A YouTube channel feature on local people opposing the military installation, and sharing their traditional knowledge about the highlands, such as the medicinal uses of plants, and other skills and resources in the territory – cultural treasures that will be lost if the militarization of Sinjajevina continues.

- An emerging international campaign about Sinjajevina is being launched and is set to broaden in intensity in the months ahead thanks to the support of the Land Rights Now international alliance that has also officially agreed to back up this case.

- There is also a new blog that has been created explaining the Government of Montenegro’s flawed decision-making process and the legal breaches in the decision to militarize Sinjajevina.

- An environmental justice atlas entry has been created in support of the initiative.

- Other international organizations sensitive to local pastoral communities have also added their force, such as the ICCA Consortium and the International Land Coalition

- There is a call for candidates to a PhD contract at the GEODE Laboratory in Toulouse (France), to work on on these endangered pastoral commons in Sinjajevina, as part of the research project IRIS: “Inspiring rural heritage: Sustainable practices to protect and conserve upland landscapes and memories”.

Profile picture (Top): Sinjajevina’s lands have historically been used and managed in common by pastoralist families from different Montenegrin tribes. Pic. by Nikola Lucic

* This article was posted initially on the Radical Ecological Democracy website on July 18, 2020.