By Viviana Asara

Barcelona’s Can Batlló platform is a radical social innovation enacting a democratized public ownership and management of public services. By blending confrontational repertoires of action with a radical politics of autonomy, movement activists and citizens intervene and decide on the planning and delivery of public services, governing them as commons, while struggling against austerity policies.

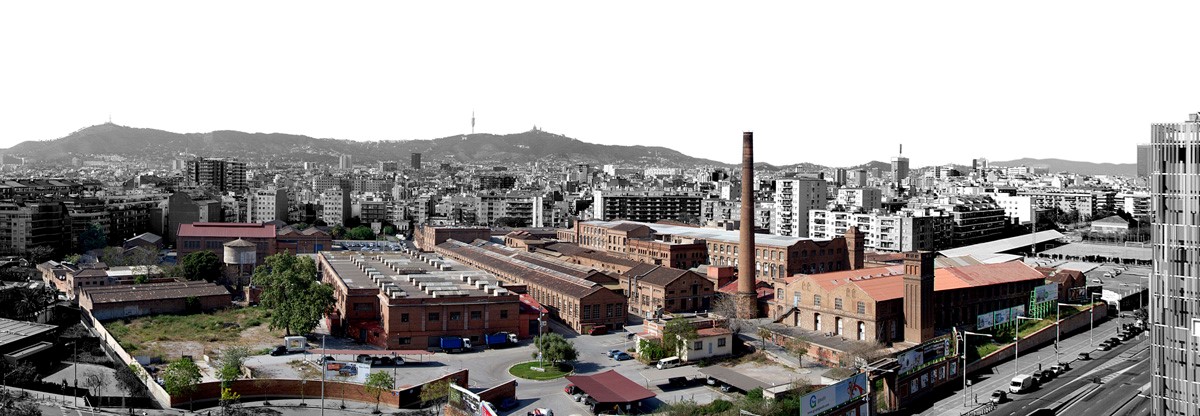

In March 2019, the social movement platform Can Batlló was officially granted by the Barcelona city council a 50-year concession of use for the Can Batlló industrial area – a 13,000 square metre space it had self-managed since 2011. The city’s decision testifies to the political struggle the Can Batlló platform has been waging over the last decade, and the important contribution it has made to the production of public services in Barcelona.

Can Batlló is an outstanding example, in Spain and beyond, of radical social innovation: a cooperative based on citizen involvement and conceived of as a provider of public services, answering material and immaterial needs and empowering marginalised social groups. However, in the context of a downsizing and restructuring of the welfare state towards marketisation and privatisation of the public sector, social innovations may inadvertently turn into an instrument for the “Janus face of governance-beyond-the-State“. Namely, while enabling new forms of participation, they can also promote non-accountable, non-representational forms of governance and become tools for privatisation and marketization strategies. Indeed, a mainstream conception of social innovation is espoused inter alia by the EU Social Innovation Policy, which sees it as a win-win solution to ensure both a downsized social spending and an active civil society, while preventing resistance.

Born out of a coalition of diverse social movement groups, such as the autonomous, squatters’, environmental, and womens’ movements, Can Batlló has so far shunned this risk faced by social innovations more generally, of turning into a strategy to offload state responsibility to civil society. In fact, Can Batlló epitomises the opposite: the strategic reclaiming of public services, and the demand for their more democratic design.

This begs two questions: what type of social and political processes and conditions can foster a democratised public ownership, rather than a neoliberal innovation? And what does public ownership actually mean?

Geographer Andrew Cumbers conceives of public ownership as encompassing all forms of collective ownership, including commons, which are subject to collective forms of decision-making, both outside and through the state, and which reclaim economic space from capitalist social relations. For geographer David Harvey, movements should engage with a double-pronged political attack to demand more public goods from the state, while appropriating and generating new commons.

The Can Batlló case is an illustrative example of the kind of relationship that can be established between the local state, social innovations in the form of commons, and social movements.

Can Batlló. Source: LaCol.

Appropriating and developing Can Batlló

Since 1973, the former textile factory Can Batlló, located in the middle-low income neighbourhood La Bordeta, had been claimed for public use in an intense bottom-up campaign by the neighbourhood movement. This led to the inclusion in the 1976 General Urban Development Plan of a green space and several public facilities in its space. However, given the decades-long failure to start the implementation of these plans, in 2009 the citizens´ platform “Can Batlló is for the neighbourhood” led a campaign with a public countdown, menacing the occupation of the site if the works did not start by June 2011.

In May 2011, with the austerity crisis and the bursting of the real estate bubble, the Indignados movement emerged. With the slogan “Real democracy now”, it occupied the squares of more than 70 Spanish cities, including Plaça Catalunya in Barcelona, with massive deliberations in general assemblies and many thematic committees. The climate of turmoil created by the Indignados movement, together with the strong Can Batlló campaign instilled fear in the newly elected city council, and finally led the municipality to grant the Can Batlló platform the use of one of the blocks through a non-legally binding contract, thus rendering the squatting unnecessary.

On 11 June, a 1,000 people entered the fenced Can Batlló industrial area in a playful demonstration. This was followed by the constitution of the first committees and deliberations on what projects to implement in the space. The seizure of one of the industrial units was conceived as a “Trojan horse”, enabling the progressive expansion to other blocks. Indeed, Can Batlló gradually expanded through collective refurbishment and modifications of the General Urban Development Plan, covering increasingly diverse realms. This expansion went hand in hand with the platform’s growing institutionalization, featuring the opening of two job positions for carrying out administrative work, and culminating with the 50-year concession of use in March 2019.

For many activists, Can Batlló was the opportunity to go further than the typical social centre or neighbourhood claim for public space, and to intervene in a political and socio-economic way, by involving spheres of life linked to housing, work, consumption, education, health, and the economy. One participant explained:

“We introduced this question in the participatory process of Can Batlló: ´do we want that Can Batlló be only a communitarian space or that it also acts like an agent of transformation for the usual circuits and parameters our life is embedded in in Sants?´ The answer was yes and from there many of us started to develop different projects that go beyond the climbing wall, or the space for doing dance courses and so on”.

The General Assembly is the sovereign decision-making body of the platform, but various autonomous committees such as the Space Design, Strategy and Negotiation, Activities, and Economics Committees take decisions on specific matters. Can Batlló is responsible for the design and content of the space, and assumes expenses linked to ordinary management, but the costs linked to refurbishment, bills, maintenance of the building, and construction of some spaces are covered by the municipality.

For the validation of projects three criteria were established: 1) their socio-economic viability, 2) their transformational potential, and 3) their close ties with the surroundings/neighbourhood. These criteria would ensure the three defining features of radical social innovation: the satisfaction of previously alienated needs, the empowerment of marginalised social groups, and eventually some changes in power and governance relations.

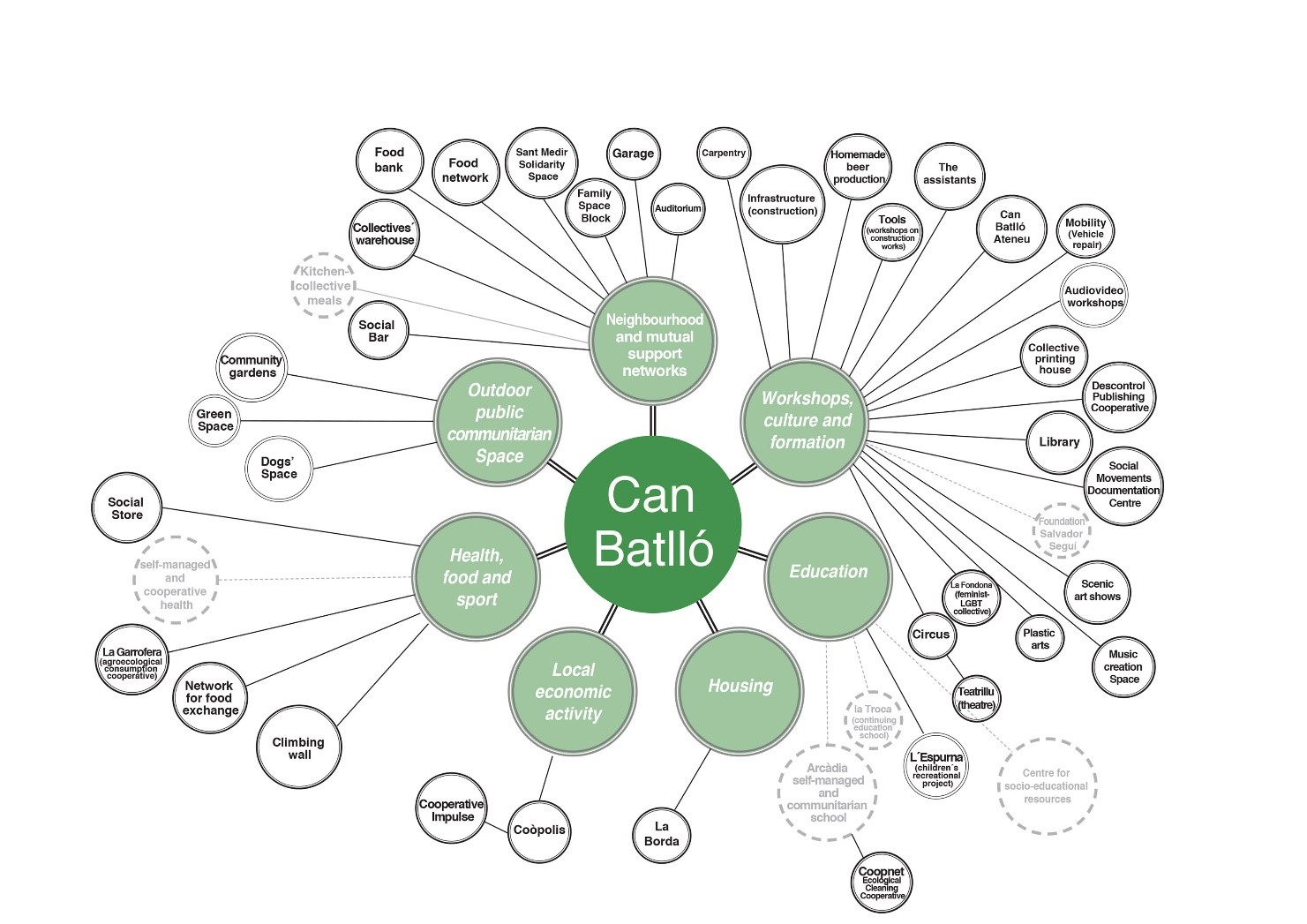

In 2017, Can Batlló had around 370 activist members and (co-)organized more than 2,000 activities for almost 50,000 users. Projects cover various spheres, including culture, sports and recreation (a public, self-managed library, a bar, an auditorium, sports facilities and artistic spaces and a publishing cooperative), spaces and networks for alternative, agroecological food production (agroecological cooperatives, a community garden, a food bank, an organic brewery), the ecological grant-of-use (co-)housing cooperative La Borda with 28 family units, as well as social and solidarity economy projects, such as the incubator Coòpolis, and work spaces for craftworks, carpentry, construction and vehicle repair.

All projects provide on a weekly basis what participants call a “social return”, namely wider social benefits and public services for the larger Can Batlló umbrella project and neighbourhood, in the form of assistance or other available resources (e.g. vehicle repair assistance, refurbishment work, shared childcare, recreational space, and various types of workshops). In addition, remunerative projects have to devote part of their revenue to the common fund, used for non-remunerative projects and for common goals and needs. All project collectives are also meant to participate and get involved in the wider Can Batlló umbrella project, at least by taking part in the General Assembly (the sovereign decision-making body of the platform) and the Coordination Committee.

Can Batlló’s projects and spheres of action. The projects in grey have not been implemented yet. Source: Can Batlló (this is a translated and re-elaborated version).

Building communitarian public services

One driving force for Can Batlló´s emergence was the desire to meet the neighbourhood’s needs. Activists reclaimed and appropriated the vast vacant space to put into practice what the state had not been capable of providing. Another core objective was to create neighbourhood spaces, by co-producing with the support of the regional and municipal authorities some of the facilities originally planned by the 1976 General Urban Development Plan: a cultural and youth centre, social housing, a park, and many new projects and public services.

Activists variously define what they are building as “public from the common” and “communitarian-public”. They oppose the externalization of public services to the private sector, which turns social rights into lucrative services for private industries, and advocate for “replacing the neoliberal conception of the public-private partnership with the public-cooperative-communitarian partnership.” According to them, such third-sector mixed schemes can reduce the public sector´s vulnerability to the relations of class and of economic power and to the 4-year political-electoral cycle, potentially acting as a safety cordon for public service protection. Thus, the communitarian-public model of service provision should complement state-managed public services.

In Can Batlló, the state supports and, in some cases, co-designs the delivery of services to guarantee their universality and gratuity. For example, the cooperative incubator Coòpolis, state funds are important so that services can be directed at all population groups, which are traditionally impervious to employment policies. On the other hand, Can Batlló also demands that some public facilities be built and managed by the state administration. This is the case of the recently built healthcare centre, for example.

Public services’ co-production can tailor services to the specific needs of users, as urban movements have knowledge about the territory, the social economy and parts of the third sector, which are out of the reach of the state administration. This is an invaluable asset for local authorities, who use this knowledge through active third sector consultation when designing innovative policies. For example, the cooperatives incubator Coòpolis directly contributed to the formulation of the new social economy policy “Network of Cooperative ” targeting job creation in workers´ cooperatives. Similarly, the housing cooperative La Borda is “a reference example” for social and cooperative housing policies in the city and inspired the design of similar programs, which were initiated with the new leftist (Barcelona en Comú) government.

Can Batlló is hence a social innovation, which embodies Harvey´s double-pronged political attack, pressuring the government to deliver the promised public services, while reclaiming them as commons and contributing to their design. As participants pointed out, “if we didn´t enter this space, there would be nothing here now.” The seizure of Can Batlló pushed the local state to rush, to put in motion, to be involved with and invest in this city space. The movement has also managed to force the boundaries of legal, institutionally accepted: the 50-year concession of use of the industrial area is unique in its kind.

The bar space of Can Batlló. Photo credit: Viviana Asara.

Between autonomy and institutionalization

One important concern for activists is the need to constitute autonomous projects which, even when benefiting from state financial support are not dependent on subsidies for their survival, so that they are armoured against changes in the political-institutional landscape. The autonomy of Can Batlló, i.e. its capacity to self-determine its activities and spheres of action, is therefore linked to the generation of an alternative economy, and income producing projects such as Coòpolis or the Descontrol Publishing Cooperative serve to strengthen the broader Can Batlló project. Participants accept funding only whenever they are autonomous to manage it, without any conditions attached. For example, the Auditorium’s architectural design was undertaken by the collective LaCol and approved by the General Assembly, but the more than €100,000 required for its construction were disbursed by the municipal government.

Clearly, autonomy here does not involve a rejection of or disengagement from the state. Obtaining autonomy implies assuming a strategic, confrontational stance towards the local administration and gains such as the concession of use are a result of the “position of strength” the movement has obtained. Conflictive negotiations are carried out both with government officials – for example when discussing changes to the urban plans – and with administrative technicians when deciding upon more specific issues such as the design of the park. They can also involve the instrument of menace or retaliation, e.g. by means of media campaign and massive demonstrations.

As recalled by a participant, when the 50-year concession of use contract was being prepared and discussed before the vote in the municipal council, “there has been negotiation [with political parties] and we said ´if you vote against the concession you are going to realize what will happen´, this was the menace that Can Batlló presented to some parties”. Participants also threatened to squat the space, declaring to political parties that “we won´t move from here, and we will continue being the same.”

The assertive political position of Can Batlló is backed by its vast number of users and its porousness to the local community, turning it into a neighbourhood space. Neighbours can propose projects to be implemented, take part in them as users, and participate in the assemblies. Communitarian public services provision thus recasts the distinction between suppliers, technicians and users and other conventional settings typical of service provision. Rather than being “passive users” of public services, citizens (self)manage, plan, design, and produce the services themselves. Furthermore, the unprecedented coalition of various movements breeding the initial Can Batlló platform contributes to the continuous concern to make Can Batlló a public space, proactively open towards theneighbourhood.

Can Batlló strives to find a balance between institutionalization and autonomy, between increasing specialization and preservation of its assembly-based democratic structure, managing political autonomy in the absence of complete economic self-sufficiency. This has inevitably involved some internal tensions and continuous debates about important decisions such as turning the Can Batlló platform into a legal association – a legal requirement for the concession of use, – opening job posts for administrative work, or starting income-generating, remunerative activities. Likewise, relations with state authorities are not devoid of challenges and difficulties, and negotiations also involved failures and unmet demands on the part of activists, as for example with the public park´s design.

However, these tensions never escalated into a “real conflict”. This is because the dialogue with institutions was ingrained in Can Batlló´s project since the start, while the division of labour (the Negotiation and Strategy Committees are responsible for negotiating with political authorities), and the internal consensus-seeking democratic structure helped to reduce frictions. Moreover, while Can Batlló evolved during two ideologically different municipality government mandates, negotiations with the more supportive, Barcelona en Comú government show that institutions do have an impact on the strengthening and consolidation of social innovations. Supportive institutions can be crucial in enabling social innovations to flourish fully, providing the necessary legal framework and financial support through which they can thrive.

A part of the community garden of Can Batlló. Photo credit: Viviana Asara.

In sum

The Can Batlló experiment teaches us that an important ingredient for a really transformational social innovation is the ability of social movements to negotiate from a position of strength, blending (threats of) disruptive repertoires of action with a radical politics of autonomy.

Rejecting and breaking the conflation of “public goods” with “state goods”, radical social innovations can struggle for a democratized public ownership and management, where neighbours and users can intervene, deliberate and decide on the planning and delivery of public services, governing them as commons.

Can Batlló shows that movement-backed, radical social innovations may even act as a safety cordon against austerity policies. While they are not by any means the solution to the pervasive effects of welfare state neoliberal restructuring, the combination of different strategies and modalities of action, and the complex but dynamic equilibrium between institutionalisation and autonomy can avoid turning social innovation into the Janus-face of neoliberal governance.

–

Viviana Asara is Assistant Professor at the Institute for Multi-Level Governance and Development at the Vienna University of Economics and Business. She is a social scientist working at the intersection between social, political and environmental issues.

This blog post is based on the following article: Asara, Viviana (2019) The Redefinition and Co-Production of Public Services by Urban Movements: The Can Batlló Social Innovation in Barcelona. PArtecipazione e COnflitto (PACO) 12 (2): 539-565.