By Alexander Dunlap

The degradation, conflict and cumulative climatic effects of industrial expansion demand a new language to identify extractive and infrastructural megaprojects. We are not dealing with “development”, but with deranged worms, octopuses and the construction of Worldeater(s).

The recent book, The Violent Technologies of Extraction: Political Ecology, Critical Agrarian Studies and the Capitalist Worldeater by Jostein Jakobsen and myself offers a provocative and unorthodox proposition. It discusses disciplinary convergences (Political Ecology and Critical Agrarian Studies), violent extractive technologies, and (“green” and conventional) extractive practices.

The book (p. 8) finds “climate change, as a technocratic framing that situates agency in the hands of climate scientists, governments, corporations and NGOs, as inadequate to confront the evolving catastrophe at hand. Crisis, meanwhile, has become a permanent and normalized feature of techno-industrial society that, we can say, is as natural as capitalism itself. In a real sense, we are governed by ‘crisis’, demanding us to scrutinize alternative framings.”

There is no shortage of measuring, accounting and alarm-raising regarding the spread of industrial wastes, extractive sties and climatic degradation, yet these processes continue with (relatively) minor concerted disruptions or opposition. The words used to discuss ecological catastrophe remain sanitized, lacking texture, and are losing meaning in the society of the spectacle.

Mainstream environmental and social movements remain largely separated and uninterested in the existent eco-anarchist struggles and Indigenous land defence, opting instead for a protest culture emerging from social media, selfies and elite-supported activist identities, which remain ignorant to existent counterinsurgency and social engineering strategies designed to keep them infantile and toothless.

The struggle against ecological and climate catastrophe is insidious and complex. Which is precisely why The Violent Technologies of Extraction, following Freddy Perlman, contends that human and nonhumans are confronting a series of beasts that form “the Worldeater”, or “Worldeater epoch,” that is consuming the planet and its inhabitants. The Worldeater “better resituates the complexity of the problems facing humanity” and “people’s agency,” as it possesses followers to build and operate its fractal infrastructural body.

Discussing the body of the Worldeater, this short article seeks to identify and animate megaprojects as the monsters consuming the world and orchestrating the mechanics of ecological catastrophe. This prose is not only playful, but recognizes how normalized processes of industrial development are spreading the Worldeater’ tentacles around humans and nonhumans of this world. Contending that “worm” and “octopus” infrastructures are the embryos of Worldeater(s), the following offers a new way to discuss megaproject development.

Source: palgrave.com

Worm and octopus megaprojects

The statist project is a colonial project. Industrial infrastructure holds the colonial-statist-capitalist continuum together. Despite the variegated levels of self-identification or popular support by various groups, techno-infrastructural development is a method by which landscapes are colonized, and people domesticated.

Popular appropriation of infrastructure is of course possible, yet we should recognize that the latter’s allure and convenience also appropriates people, slowly and progressively shaping and re-shaping their psycho-geographical perceptions and cultural values. The struggle against infrastructure development are everywhere—in various conflictive intensities—exemplified by cultures of Indigenous land defense across the world, and by the Zones-to-Defend (ZAD) concept in France. This hostility towards infrastructural development deserves accurate ways to describe what megaprojects are doing to ecosystems and the planet.

Freddy Perlman’s 1983 book Against His-Story, Against Leviathan (pp. 189, 29) describes statist development as “a giant worm” and “an artificial octopus.” Perlman anthropomorphizes statist subjugation of peoples, which also applies to megaproject development. This description of statist development operates on a smaller-scale through infrastructural colonization that dominates habitats, domesticates people and cultivates socio-cultural homogenization through worm and octopus-like infrastructural expansions.

The giant cyborgesque worm, Perlman explains, crawls across the earth “accumulating” people into its politico-economic project, constructs infrastructures, and de- and re-composes its parts to replicate itself. Taking struggles against infrastructure in France as an example, The Notre-Dame-des-Landes ZAD, fighting an airport, resembles a localized struggle against a worm megaproject: one directly dominating and suffocating large swaths of land with asphalt tarmac, buildings, and an entire artificial wormlike apparatus operated by people.

The worm megaproject modality applies to dams, mines, factories, ports, nuclear, solar and coal fired power stations. The central attribute of worm infrastructures is their high-density and occupation of large swaths of land and vital resources with rippling socio-ecological impacts. Capital is the blood that circulates through these beasts, where the worm serves as a central node of vital socio-ecological consumption.

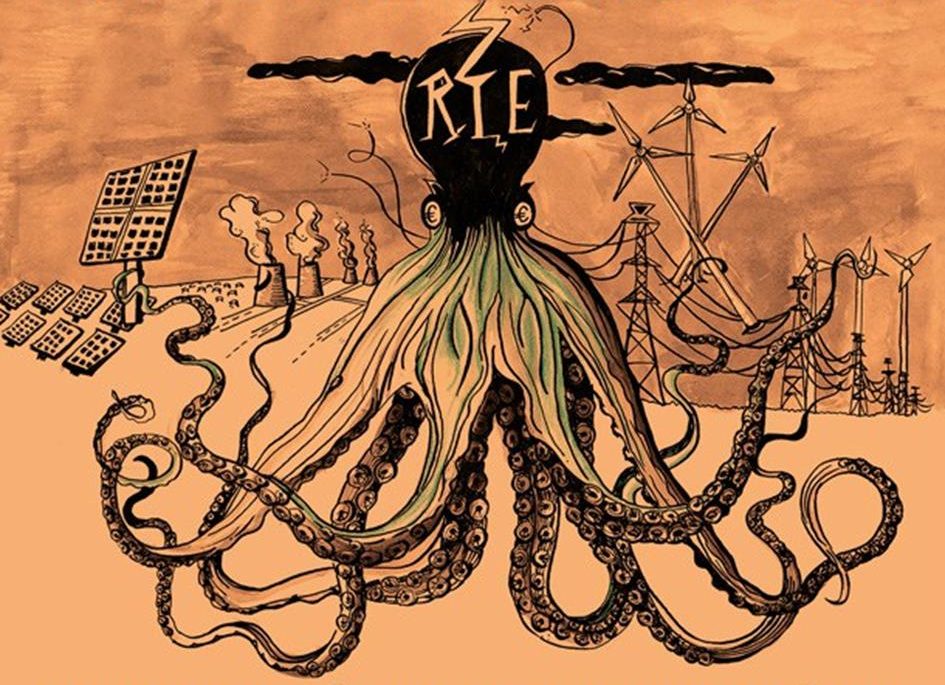

Meanwhile, the artificial octopus stretches “its tentacles to every part of the globe,” where the “New World becomes just like the Old. Or rather, the New World is consumed by the Old, it ceases to be a separate entity, it is all part of a single commercial empire” (p. 279). Octopus megaprojects consume spaces in networked and (administratively) decentralized ways to promote commercial and political flows. The L’Amassada Commune in the French Aveyron region represents a struggle against the spread of octopus infrastructure (see the featured image).

L’Amassada blocked the construction of an energy substation and high-tension wires in resistance against the anticipated intensification of wind and solar (or, more accurately, fossil fuel+) projects. Seemingly innocuous octopus infrastructures, such as wind parks, begin by colonizing space with the fortification and construction of access roads. This affects the soil composition and the hydrological table, combining with habitat clearance, not only for roads, but also high-tension wires and wind turbine construction sites.

Wind turbines depending on the geography, have foundations that range between 7 and 14 meters (32-45 ft.) deep and about 16-21 meters (52-68 ft.) wide. This means any ground water, as in the case in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec region, must be sucked out with the application of chemical solvents to harden the ground. Placed near or within marine areas, turbines have severe impacts on shrimp, fish, turtles and other sea life from electromagnetic currents, vibration, sound waves and aircraft warning lights.

Once the wind turbines are in operation they kill large amounts avian life and systematically leak oil into the ground from their propellers that has resulted in reports of cow deaths and infertility. This all happens on the back of worm megaprojects that mine raw materials, process the metals and manufacture the wind turbine components. This also includes decommissioning, which results in an abundance of infrastructural and e-waste.

Consuming more space, octopus infrastructures dominate landscapes in strategic spatial and networked concentrations to circulate materials, energy, and capital, all the while exerting a dispersed network of control over space. Highways, pipelines, trains, energy infrastructures, and wind turbines, form the tentacles and suction cups of octopus infrastructures. The head of the octopus are control centers and linkages within the heart of worm infrastructures, such as Smart City, wind park and electrical grid control rooms.

Octopus and worm infrastructures operate on different scales, or growth stages. These modalities of infrastructural colonization have also morphed, networked and materialized the conquest of political economy across socio-ecological space. Together, they give life to the Worldeater, the Leviathan Freddy Perlman described with poetic vigor.

Depiction of the Worldeater. Credit: Anaïs.

Why worms, octopuses and the Worldeater?

People need to change their relationship with techno-capitalist infrastructures. The last two centuries can be described as forced and learned dependency on energy intensive and degrading infrastructures. This coincided with the attempted eradication of eco-centric cultures, medicines and convivial infrastructural practices and design.

This developmental trajectory, even in the face of ecological and climate catastrophe, continues with little reflection. The culprits and root problems need to be identified. Furthermore, infrastructures demanding global and energy intensive supply chains and corresponding forms of wage and forced labor need to be acknowledged in negative terms: deranged cybernetic worms and octopuses possessing and consuming human and nonhuman resources.

Currently, we are watching a process of progressive worldeating (commodification, degradation and destruction) with no signs of it slowing, let alone stopping anytime soon. It is time to relate negatively to these processes: no more technical and academic words to perform apologetics, promote their enchantment, learned dependency and socio-ecological costs. This is a conversation about demonic worms, octopuses and the Worldeater(s).

Alexander Dunlap is a post-doctoral fellow at the Centre for Development and the Environment (SUM), University of Oslo. @DrX_ADunlap. Featured image: Illustration on L’Amassada, 2017 demonstration poster against RTE transmission grid. Credit: Anaïs.

One Comment