By Julie Sze

What does the current moment of danger mean for the intersections of environment and justice? EJ movements help us see how unjust environments are rooted in racism, capitalism, militarism, colonialism, land theft of Native peoples, and gender violence. At the same time, they inspire optimism and help us ‘forward dream’ in moments of crisis through resistance and the cultures, stories, and imagination they mobilize.

Growing up in 1980s New York City, I was oblivious to the rise of hip-hop, although I could see what hip-hop was responding to: the state-sanctioned decline of the City, based on racism. My preferences ran more the oldies station, and the sounds of Motown and the 1960s and 1970s. In 1971, Marvin Gaye, in his album and song, asked “What’s going on?”. He linked racism and war, contrasting leafy suburbs and decayed cities. These spatial and environmental critiques are further developed in another classic from the album, “Mercy Mercy Me, the Ecology”. Trenchant political critique never sounded so good. I learned how to understand my urban environment beyond words. That was a cultural legacy I am grateful for.

It was also a political stance, that continues its relevance, now more than ever. We are living through and at a precarious environmental and political moment, with the warmest years ever recorded, and with active assaults on the rights of the disenfranchised. Important social movements for environmental and climate justice are mobilizing large numbers of people with a broad national and global impact outside of their local contexts. Oil pipeline protests on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation; responses to reports of mass lead poisonings in Flint (Michigan), mobilizations against police killings of African-Americans and other people of color, impassioned entreaties and testimonies of small Pacific Islands and Arctic indigenous voices in response to rising flood waters from climate change, and direct actions against high-end ‘sustainable’ developments in gentrifying cities, comprise just a snapshot of the hundreds, if not thousands of protests in the United States that foreground the convergence between “environmentalism” and “social injustice/ inequality.”

It is precisely in this moment that understanding environmental justice movements and the theories they advance is essential. My focus here is on social movements and the cultures and analytics they advance and embody. Environmental justice movements offer important guideposts for troubled times, because these movements and the people who make them have long-standing political commitments, and, crucially, have done important ideological work grounded in everyday and long-lasting struggles for justice.

My book Environmental Justice in A Moment of Danger offers an over-arching synthesis of environmental justice. It examines how organizers, communities and movements fight, survive, love and create in the face of environmental and social violence that challenges the very conditions of life itself, through many different struggles: for climate, environmental and health justice and against pollution and extraction in its myriad iterations. It connects problems and protests across time and between spaces, and uses the interdisciplinary tools of both environmental justice and American Studies, principally, in cultures of social justice. American Studies and environmental justice, taken together, help situate and understand both the sources of these problems and their responses. It spotlights how diverse peoples and communities invoke history and justice in facing environmental problems in an interdisciplinary and comparative way.

The central questions of my book are: What does this moment of danger mean for environment and justice? What can we learn from struggles for environmental justice? The main contention is simple: environmental justice movements –what they are, who is involved, and what they are fighting against– offer an ideal standpoint through which to understand historical and cultural forces, and, most importantly, resistance to violence, death and destruction of lives and bodies through movements, cultures and stories. The starting premise of the book is grounded in American Studies scholarship: that unjust environments are rooted in racism, capitalism, militarism, colonialism, land theft of Native peoples and gender violence.

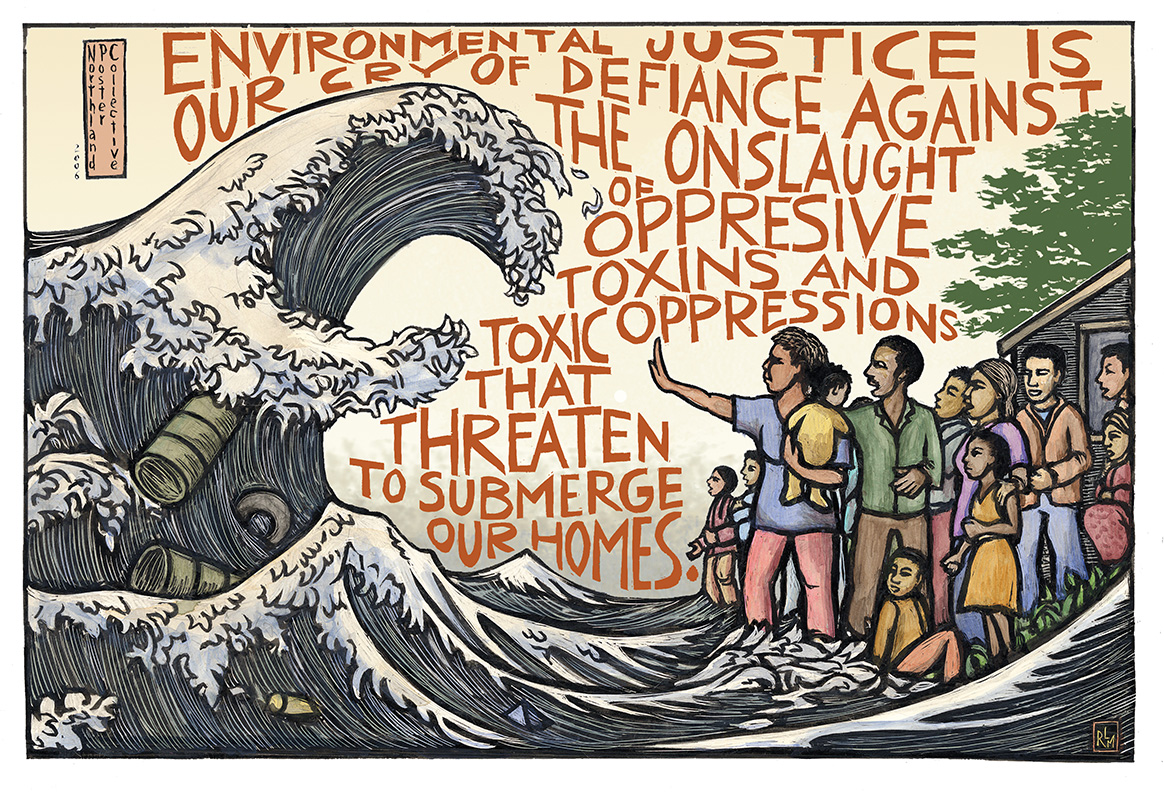

Art for “Paying Homage: Soil and Site Environmental Justice Summit organized by cultural organization Artspace (New Haven, Connecticut) on September 8, 2018, at the Yale University Art Gallery.

Forward Dreaming in Moments of Crises

Environmental justice scholars and environmental justice organizations have for well over three decades articulated how race, indigeneity, poverty and environmental inequality are linked in a toxic brew. The arguments that environmental justice advocates have been making are gaining visibility and traction outside local communities facing specific pollution problems. Environmental justice arguments make sense to more and more people who, in less obvious moments, may have settled for an “end of history” or a “color-blind” post-ideological ideology. American Studies tools and approaches, in teaching and scholarship, can inform many fields. Antonio Gramsci’s notion of hegemony defines a process in which multiple institutions and processes work together, to garner consent and the possibilities for transformation. Hegemony shows change over time, and shows how what is “common sense,” becomes naturalized, and is actually a product of institutional and historical forces that are complex, and contradictory.

Gramsci’s famous motto ‘Pessimism of the Intellect, Optimism of the Will’, structures my teaching, my outlook, and indeed, this book. The intellect, however, is not just a preserve of the pessimist. This book offers environmental justice struggles as a set of cautiously hopeful stories about the future which we need desperately now. Using cases of environmental injustice and their response by social movements, analyzed with American Studies methodologies, and infused with Gramscian optimism/pessimism, I pose a series of essential questions: What is Environment? What is Justice? What is Environmental Justice? What is Environmental Racism and Environmental Inequality? How does Environmental injustice work? Why does it Persist? How are the past and the present interconnected? What is being done to bring us to a more environmentally just U.S. and the world? What is the role of hope and imagination in dark times?

The optimism and the pessimism, is that environmental justice movements have been fighting against authoritarianism, extractive and rapacious capitalism and government collusion for a long time. Some of the struggles have been successful, and others less so, although my interest is not on quantifying victory or failure. Focusing on culture, change and community offers a crucial explanation for the predicament identified by revolutionaries and intellectuals. Gramsci asked why political revolutions don’t happen more frequently, a question that needs serious attention.

Art by Ricardo Levins Morales, part of his “Health & Environment” notecard series.

My (tempered) optimism, and this book, is structured by experience, analysis, and a faith in environmental justice movements and in my everyday interactions with people (especially the very young and the elders). As the university grows more diverse in terms of its students, and with a greater awareness of students and the broader public of justice-oriented environmental movements, particularly through social media, the prevailing culture and production of ignorance about environmental injustice and racism may change.

Who gets to live and who is made to die? Racism, capitalism, militarism, colonialism, land theft of Native peoples and gender violence –in short, culture, history and politics– shape the answers to these questions. These trends, these “things that beat you down” are connected, in the same way that Freddie Gray’s extreme lead poisoning is connected to the state violence in the van that killed him. Social justice advocates and movements do important ideological work in stripping away status quo power relations. Gramsci’s notion of hegemony illustrates how what is “common sense” becomes naturalized through cultural forms and is actually a product of institutional and historical forces. Advocates and movements denaturalize the common-sense, and in doing so force everyone to confront the beasts within the United States that seem ready to devour the many in the service of the few. The tools of American Studies are needed to understand the problems we face, in part because of the ideological terrain in which political and revolutionary struggle begins.

As black radical singer and poet Gil Scott Heron said in a 1990s interview on the history of his ground-breaking song, “The Revolution will not be televised,” the Revolution was about how “the first change takes place is in your mind. You have to change your mind before you change the way you live and the way you move. So when we said the ‘Revolution will not be Televised, we were saying that the thing that is going to change people is something that no one will ever be able to captured on film. It will just be something that you see and suddenly you realize that I’m on the wrong page or I’m on the right page but I’m on the wrong note. And I’ve got to get into sync with everyone else to understand what’s going on this country”.

https://youtu.be/qGaoXAwl9kw

My book offers a useful primer for those who intuitively understand that environmental racism and environmental injustice exist and want to make the world less environmentally damaged, structured by and invested in racism, class inequality, gender violence, and attacks on Indigenous rights and land claims. Chapter One, This Movement of Movements lays out the broadest questions in environmental justice, as well as the intellectual stakes in how these questions are posed and engaged. The phrase “movement of movements” was coined by Native activist Dallas Goldtooth, and connects to what Cole and Foster, in From the Ground Up: Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement, identified as the six “tributaries” (or six movements) that lay the foundation for this Movement in the United States: civil rights, anti-toxics, academics, Native American, labor, and mainstream environmental movements. The heart of this first chapter is an overview of the events that took place at Standing Rock, drawn from activists, scholars and allies who foreground indigenous land rights and sovereignty claims. Chapter Two, Environmental Justice Encounters: Pollution and Persistence, uses two case studies to illustrate this analytic: mass, government sponsored lead poisoning in Flint Michigan, and the Central Valley region of California facing air pollution, water contamination, pesticide exposures and other hazards (natural and social). The final chapter, Environmental Justice as Freedom, argues that struggles for environmental justice are freedom struggles. This chapter asks these central questions: What is being done to bring us to a more environmentally just U.S. and world? What is the role of imagination in dark times? It uses a number of examples of cultural projects examining climate disruption, social art documentation, cooperatives and films to highlight anti-capitalism, solidarity, and anti-consumerism, including examples from Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans and post-Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico.

Standing Rock protesters, emphasizing the defense of the sacredness and life of the environments they are part of. Photo courtesy of Leslie Peterson’s Flickr page, and republished by Georgetown University’s Berkley Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs

The optimism of the intellect is drawn from the recognition that individuals, in their dizzying diversity, comprise a loose but confederated environmental justice movement. Many people, particularly elders and youth, have experiences and perspectives that can offer wisdom to those who share values of community and want to protect the broad notion of “environment,” capaciously and not narrowly defined. The optimism I feel is in the students I meet, many of whom are unhappy with the world that past generations have made, and who want to reshape the world with different images and ways of being –away from neoliberalism and consumerism, with intersectional justice as its beating heart. They want to bend the arc of justice back into balance to counter a political moment based on death, extraction, violence, domination and hierarchy.

My hope (and contribution), is multi-fold: to offer a starting point for those interested in particular struggles and link these together as they have been linked by activists themselves, and to spark imagination and hope. The book honors the work of activists who have been and continue to be in the struggle. It also materializes that support, through donating the royalties of this book to two organizations in places I have worked, Community Water Center, which works on water justice and is in California’s Central Valley, and UPROSE, a community-based environmental and climate justice organization based in Brooklyn, New York, which I have worked with for 20 years.

Here’s to making the world-not Flint, but Stevie Wonder’s Saturn from the majestic 1976 album Songs in the Key of Life. His call for “Love’s in Need of Love Today”, is a message we need now more than ever.

Julie Sze is a Professor of American Studies at University of California, Davis. She is also the founding director of the Environmental Justice Project for UC Davis’John Muir Institute for the Environment. Sze’s research investigates environmental justice and environmental inequality; culture and environment; race, gender and power; and urban/community health and activism.

One Comment