By Subina Shrestha

After a weekend interacting with schoolchildren about the climate crisis, a Norway-based researcher reflects on why recent decisions made by the Norwegian government can be defined as acts of intergenerational injustice.

I am currently sitting on a train from Bergen to Oslo. There are two things you need to know about this train ride. It is ridiculously long (7 hours) for the distance it covers (430 km). But it is supremely picturesque- some of the best views that Norway has to offer. As the train passes through the spectacular landscape of trees that are transitioning from green to yellow and red- a sign that autumn is upon us- a thought strikes. What if the next round of wildfires is about to happen here?

It’s a morbid line of thinking, I know, but allow me to give you some context. I am a researcher at the Centre for Climate and Energy Transformations (CET) at the University of Bergen in Norway. On 22nd and 23rd September 2023, The Centre participated in Bergen’s Forsknings-torget (Research Fair), which targeted young school kids. Our stall had three activities to give kids a hands-on experience on climate change. First, we asked a difficult question: “Who do you think is most responsible to solve the climate crisis?” The options were: 1) the individual self, 2) businesses and corporations, and 3) politicians and the government. Many replied that the individual self is the most responsible. When asked why, some of the children (and a few accompanying adults, too) said that they could make more sustainable choices in their everyday lives. Upon prodding about the role of state-owned fossil fuel corporations like Equinor, we only got a reflective pause as an answer. Whilst individual action and accountability are certainly important, shifting the responsibility to individuals is often a greenwashing strategy promoted by fossil fuel corporations.

The climate dilemma. Silje Kristiansen, Associate Professor at CET interacting with a kid at the Bergen’s Research Fair. Source: Judith Louise Reczek Dalsgård.

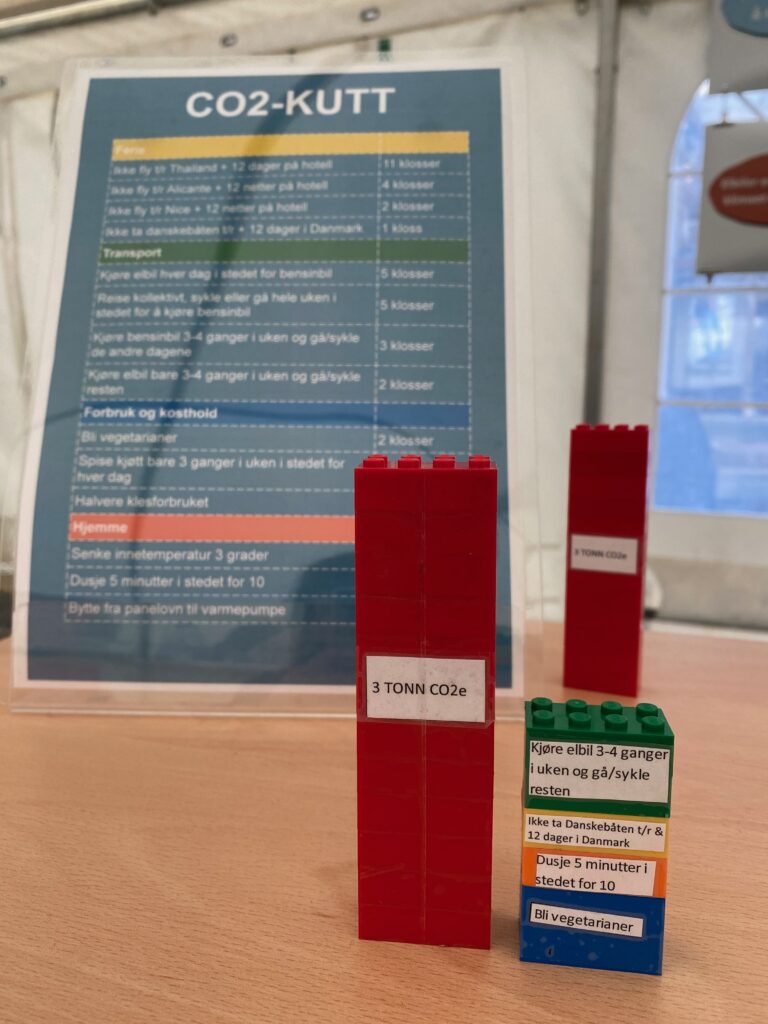

The second question was: “What activities are you willing to give up in order to reduce your CO2 emissions by 3 tonnes?” This question garnered the most interest from the children because it included Lego blocks. Each activity was a Lego block with its associated emissions, and they had to stack these blocks on top of each other to add up to 3 tonnes. I had to try to explain the notion of CO2 emissions to an eight-year-old. Neither of our first language is English, and my Norwegian is existential, at best. So, all I could come up with is that CO2 is a harmful gas in the air, and we should do everything we can to prevent CO2 from being emitted. With this basic explanation, the eight-year-old decided that he was willing to give up a 4-day family trip to Thailand, but not to Spain.

Interacting with children using Lego blocks.. Source: Judith Louise Reczek Dalsgård.

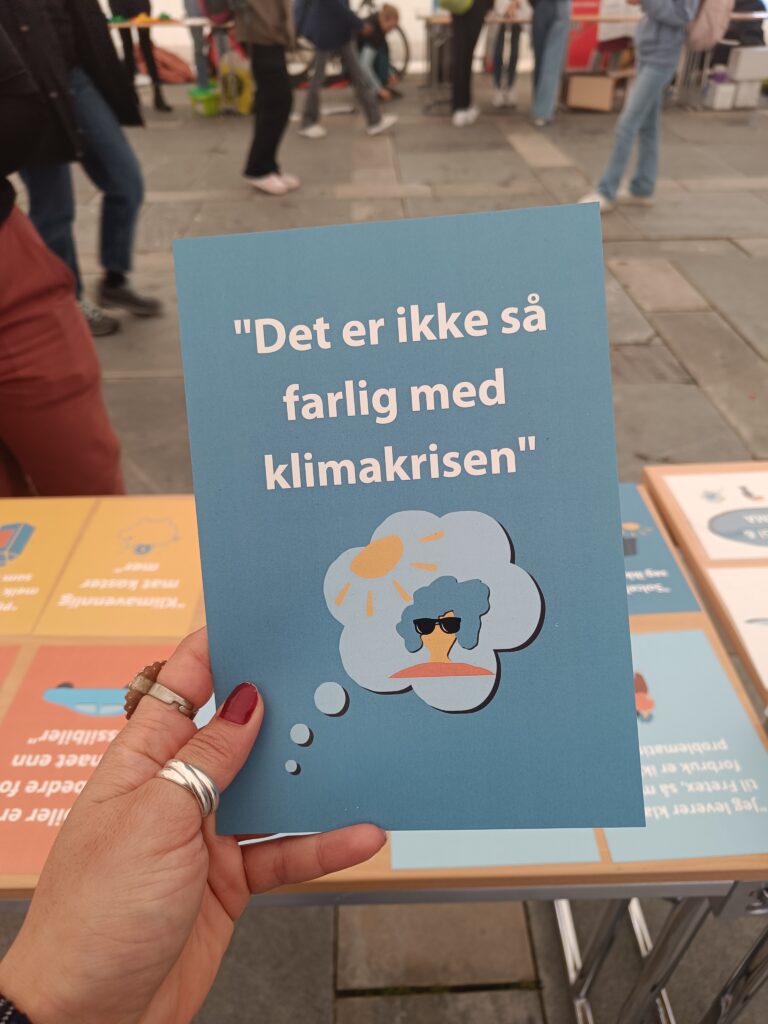

The final activity was the most interesting for me. We proposed 10 climate myths that the kids had to analyze and decide whether they were true or false, and why. Of course, as they were all “myths”, they were all false. However, it was fascinating to see how engaged, knowledgeable and assertive these young kids were on the issues of climate change.

One of the myths was “Electric vehicles (EVs) are not better than fossil-fuel cars.” A young boy (maybe 10 years) said that it was technically false, but ultimately true. I was genuinely curious about what he meant because he had done such a good job of busting the majority of the myths. And he said: “I know electric cars are slightly better than fossil-fuel cars. But really, we should not be using cars. I think we should use cycles more!” As a mobility researcher, I was proud of this kid! Another myth we proposed was “Biking lanes are too expensive and a waste of money.” Many of the kids said that biking should be encouraged in the city because: “Biking is fun”! Arguably, Bergen is trying to make itself more bike-friendly despite its unforgiving topography and the car-centric orientation of the local government.

There was, however, one myth that many had trouble debunking. “The current climate crisis is not dangerous”. Most kids agreed with the statement, and my colleagues and I had to tell them that unfortunately it was as false as it could be, and then explain why.

When I was in secondary school, I was learning about the impacts of climate change, not experiencing it year after year. The lives that these kids lead are quite different. Globally, this year has been particularly bad – “crazy off-the-charts records” – on so many fronts. The smoke from the Canadian wildfire made its way to Norway. Many Norwegians had to reconsider their holiday plans as ‘climate boiling’ emerged in Southern Europe, the most popular summer getaway.

The climate crisis is not dangerous. Source: Subina Shrestha.

The severe lack of preparedness to absorb climate-induced extreme events (intense rainfall and flooding) was evident when the storm “Hans” hit the country. Dovrebanen, the main train line between Oslo and Trondheim, is still not up and running as the railway bridge washed out and collapsed in the storm. The service has been interrupted indefinitely. Similarly, entire houses were washed away, several communities were evacuated, a dam had partially burst, and all main roads between Oslo and Trondheim remained closed for days.

The climate crisis hit Norway with a bang, and these kids were well aware of the crisis situation. The storm and its adverse impacts were all over the news as well as general conversations as chaos ensued in the southern part of the country. When my colleagues and I used these very recent events to showcase how dangerous the impacts actually were, I witnessed how the curiosity on their faces got replaced with shock and horror. Surely one can imagine the expression on the face of kids as young as 8-year-olds being told that their present is grim! And we refrained from stating anything about the future.

I generally love my job, but it is on such occasions that I start having doubts about it. It becomes too much of an emotional undertaking, especially when interacting with kids and trying not to think about the kind of future they will ‘inherit’. How can I keep my spirits high when talking to kids?

A few days after the Research Fair, the UK government approved the Rosebank project involving Equinor (the Norwegian state-owned Oil Company) for expanding oil and gas fields in the Shetland area of the North Sea. This is despite the International Energy Agency explicitly stating in 2021 that no investments in new oil and natural gas fields should be allowed to limit global heating to 1.5˚C above pre-industrial temperatures. Two years later, the state-owned oil company is doing the exact opposite in order to contribute to “energy security and creating jobs for Britain”, which is the politically correct term for profiteering from oil money. Earlier in 2023, the Norwegian government had approved the development of 19 new oil and gas fields with investments exceeding $18.5 billion. Ironically, these decisions are advertised as being on track with climate action, arguing that the country supposedly has some of the greenest oil fields in the world!

The havoc that the current climate crisis is unleashing is undisputable: even kids as young as eight-year-olds, know it. They are living it. The social ramifications of political choices are evident. Our kids will suffer. Ample research points to how children are especially vulnerable to the adverse impacts of climate change. Within Norway, the extent of vulnerability is different across communities and contingent on socio-economic conditions, but child poverty is increasing across the country. Beyond the Norwegian borders, in some of the poorest countries, children’s vulnerability to the impacts of climate change is exacerbated much more. Yet, the Norwegian government is cutting its international aid ambitions, avoiding its global responsibility as one of the world’s richest countries (a significant portion of this national wealth is from exporting oil and gas).

Proponents of intergenerational justice bring children to the fore of climate justice: current climate (in)action is an infringement of children and youth rights. In Norway, the rights of children are in line with the Article 12 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which state that children of all ages must be recognised in state decisions as valid agents with the right to speak and to be heard. It also states that it is the responsibility of adults to provide adequate spaces and overcome possible barriers of language, expression or thinking patterns throughout the different stages of childhood. With these greenwashed decisions, the Norwegian government is failing children- Norwegian or otherwise.

Young people around the world are already doing a commendable job to bring states and companies to account. Six youth in Portugal sued 32 countries for their climate wrongdoings. Fridays for Future is now a global phenomenon. Youth activism is on the rise worldwide. Perhaps it’s time that governments across the world find ways to engage more with kids and ensure that they actively participate in deciding how their future should look like. It is beyond unfair that they don’t get a say in how their future is, as decisions today discount the lives in the future, ultimately resulting in this crisis situation. So then perhaps the question we (adults) should be asking ourselves is: how can it be ensured that children play a more active role in climate decisions? And how can this happen without them experiencing even more climate anxiety?

One approach could be to use art-based methods to elicit children’s concerns and visions for the future. Researchers, teachers, policymakers could collaborate and learn to be more imaginative in this way. Another approach could be conducting hands-on projects with children to transform their communities, such as community gardens and bike-bus initiatives, to name a few.

The Bergen-Oslo train journey. Source: Vy.no

As I am toward the end of my train ride from Bergen to Oslo, I catch a glimpse of a mother-daughter duo reading their respective books, and I find myself thinking that perhaps Lego blocks are better than books to engage with kids on climate change. They represent a more tangible way to imagine, create and re-build things and after all, they were a huge hit amongst children at the Research Fair.

Profile image: Students gather in front of the Parliament building in Oslo on March 22, 2019, as part of the global youth climate strikes (Tom Hansen/AFP/Getty Images). Source: Unfazed by youth climate protests, Norwegian gov expands Arctic drilling – Eye on the Arctic (rcinet.ca)