by Guy Jackson

Climate-exacerbated disasters in Europe can illuminate the increasing economic and non-economic losses being experienced globally. From solidarity in loss may come solidarity in action, to fight the systems of oppression that create unequal vulnerabilities and fuel climate change.

Ecological violence is easy to ignore when shielded by expropriated wealth. A relative stability suffocates the cries of those suffering at the edges. Yet, the summer of 2022 has interrupted this false sense of security in Europe, with rivers running dry, crops failing, seemingly endless heatwaves and uncontrollable fires.

We live in an era of incalculable losses. The latest IPCC report again made it clear that climate change threatens to collapse the socio-ecological systems that humans depend on for their survival and flourishing. These permanent, irreparable losses will continue to worsen over time, especially as wealthy nations over consume and societies remain dependent on fossil fuels.

The growth imperative of capitalism demands the over production of non-essential consumer products. To make the most profit, these products are typically produced in developing countries from exploited labour with materials often violently extracted from the Earth. Be it energy or fuel, electronics, or clothing, Europe along with other imperial states, and wealthy elites everywhere, disproportionately consume and waste. This is a key driver of fossil fuel use and a cause of climate change.

The climate crisis remains very abstract to most of the rich world. Although outright climate denial is passé, few truly grasp the actual implications of the trajectory we are on. Most remain disconnected from their environments and inherent dependence on biodiverse ecological systems. If people don’t notice the loss of something, can it even be considered a loss?

Yet, many of those most vocal about climate change risks often misattribute causality for the climate crisis and overlook the processes and factors that (re)create unequal vulnerability between and within regions. Like the broader ecological crisis, climate change is tied to the colonialism-capitalism-imperialism nexus. The development of capitalism led to the subsumption of human and more-than-human life into property and commodity production regimes, which created a new world ecology through extraction of value, rule of the market and growth predicated on the separation of humans and nature. Through colonial expropriation of wealth and continued unequal exchange, those nations historically most exploited remain the most vulnerable. Although carbon emissions drive climate change, the problem has far deeper roots.

The disconnect between a relatively protected existence shared by many, but not all, in Europe and those eking out bare existence in territories carved up by empires and exhausted by capital, is immense. A child growing up in poverty only has their potential labour to sell if they are lucky enough. A widow, whose husband has died trying to reach Europe, attempts to subsist on parched land and empty shelves. These are the realities obscured by linear progression models of capitalist development. Climate change affects the increasing variability of weather, but are the historical-structural determinants of vulnerability that create adaptation limits amongst those living exposed to the winds of climate change.

Europe has had disasters before and will have them again. This summer might be different, if the momentum of the current crisis is turned towards addressing the metabolic imbalance tied to wealthy countries that fundamentally drives climate change. Subjectivities are fickle, however, and even the drying out of major rivers in Italy and France might not turn the tide. When the fires are all put out and the rivers begin flowing again, a perceived return to normality can occur relatively quickly. In a privileged world in which distractions abound in air conditioned, comfortable flats and houses, it is easy to ignore the manifestations of environmental violence.

Forest fires in Corsica during the summer (credit: Bas Kers).

The fires were shocking in places such as Gironde, Sicily, and Vila Real. The ongoing droughts are severe, potentially unprecedented, and are causing significant economic losses. The heat that baked the continent and caused the vulnerable to perish, reduced to “excess deaths” in statistical spreadsheets, was not “just summer”. Taken together, and with the growing consciousness of climate change, they form a potential critical juncture. These environmental disasters, coupled with an inflationary crisis, have made the future seem less certain for many who could casually glance at the news and see reports of famine in the Horn of Africa or monsoon floods in Pakistan but felt sheltered in their little corner of the world.

Whether or not this summer of reckoning with losses and damages leads to change in Europe, let alone a realisation of the way Europe’s comforts reproduce both extractive violence and violent weather around the world, remains to be seen. It is our job, those that think, write and organise around environmental injustices to ensure that this critical juncture does not go to waste. I believe one way forward is to draw from and articulate the scientific and normative strength of the politics and science of loss and damage.

Loss and damage is a political object tied to international climate change governance, in which particularly at-risk countries argue, mostly to deaf ears, for compensation for unavoidable climate change impacts such as loss of territory from sea level rise. It is also an emerging science that explores the kinds of economic and non-economic losses and damages which are being experienced by people. Climate change is leading to the loss of things people value, which can be tangible (e.g. settlements, houses, crops) and intangible (e.g. sense of place, identities, and Indigenous and Local Knowledge).

Both the international policy and the science of loss and damage are mostly framed as issues for nations and people in the global South, but people everywhere, at all development levels, are experiencing losses and damages. Bringing attention to this whilst emphasising the disproportionate burden of losses among those marginalised economically, socially, and politically, whether globally or within Europe, is necessary.

The term adaptation limits is a central concept in the science of loss and damage. Adaptation limits can be hard or soft. Hard adaptation limits include biophysical limits of coral reefs due to increasing sea surface temperatures and ocean acidification. They can also relate to social systems in which adaptations are beyond the financial, technological or social and cultural capacities of societies. Yet, perceived hard social limits often are due to societal values and political choices. For example, many people suffer and die during heatwaves due to poor quality and overcrowded housing, and this could easily be remedied by government intervention into the housing sector. Likewise, droughts are often framed as causing famine, when decades of research demonstrated it is about lack of access (financial, social) to food more than a lack of availability. These necropolitical calculations about the distribution of resources can generally, though not always, be considered soft limits as opposed to actual hard limits.

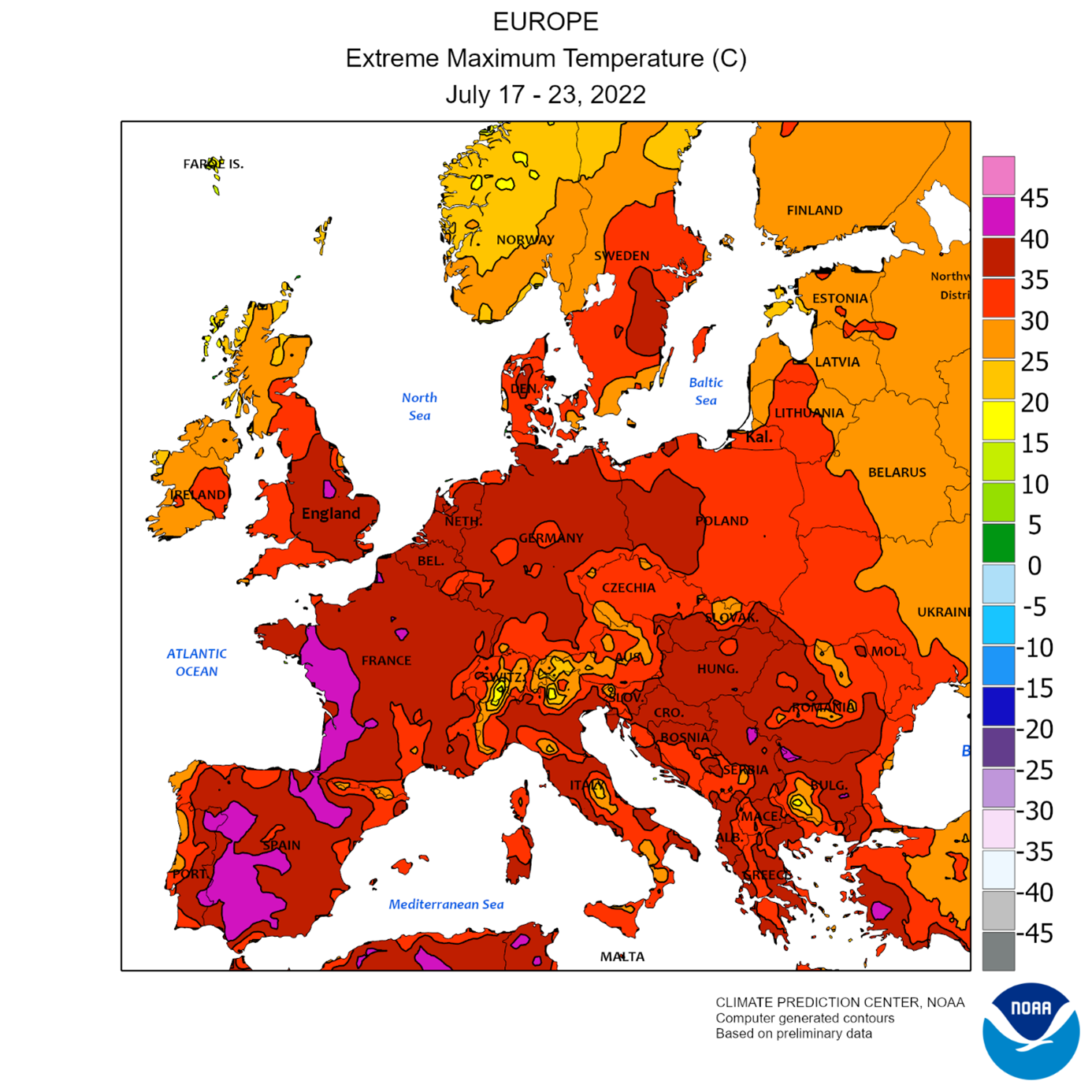

Maximum temperatures in Europe July 17-22, 2022 (credit: NOAA)

Nonetheless, the difference between adaptation limits in Europe compared to, for instance, Vanuatu is striking. Vanuatu, although rich in traditional knowledge on how to manage environmental hazards, has constrained institutional and financial capital to reduce risks and respond to disasters, partly due to uneven development and unequal exchange. I previously showed the colonial processes that led to increased vulnerability in Vanuatu, including missionaries and colonial officers encouraging Ni-Vanuatu people to build settlements on the exposed coastline. Today, lower elevation islands are rapidly disappearing with limited options available apart from retreat or relocation. The realisation of unavoidable impacts of climate change, that Vanuatu contributed almost nothing to, made it a champion of raising the issue of loss and damage within the UNFCCC process in the early 1990s. However, even with a desire to reduce risk and help those that are being affected by slow and sudden onset extremes, it is just not possible for Vanuatu to reduce most risks across their 65 inhabited islands, especially when frequently impacted by category 5 cyclones.

In Europe the limits to adaptation are primarily related to values and ethics. It is within the capacity of European nations to fortify their settlements, transform agricultural systems, and compensate those experiencing unavoidable losses domestically and internationally. It just chooses not to.

With the disasters in Europe continuing, there will likely be a push to take greater action on climate change. This must not become insular and exclusionary in nature. With the realisation that climate change is affecting even the wealthiest places, this must not blind us to the heightened, socially constructed vulnerability in other locations and of specific social classes. Nor does it mean that we should neglect those in Europe who are more vulnerable to, for example, heatwaves, due to poor quality housing, or flooding, due to cheaper land being on floodplains. The growing experience of loss and damage calls for solidarity.

Europe’s summer of reckoning with losses and damages has made it clear to many that climate change is happening now, and it is not just a problem for the global South. However, those who have benefited most from extracted wealth remain relatively more protected from the climate crisis despite disproportionately contributing to it. Europe’s loss and damage must be linked to capitalist political economy, not just decontextualised carbon emissions. When people tell stories of the droughts and fires in France and Spain, we must remember and elevate the untold stories of those on the frontlines of industrial capitalism and climate change. The underclasses of Europe and the peasant and proletariat around the world must have recognised their shared precarity.

The climate-exacerbated disasters of Europe can illuminate the increasing economic and non-economic losses being experienced globally. Each of us must fight to name the systems of oppression that create unequal vulnerability and fuel climate change. From solidarity in loss may come solidarity in action.

Guy Jackson is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Lund University Centre for Sustainability Studies. He is currently working on the project “Recasting the disproportionate impacts from climate change extremes”, which focuses specifically on climate change loss and damage. His work explores socioecological relations and the (re)production of vulnerability over space and time.