By Ankita Shrestha

Communities are not always formed by the social boundaries that we, as researchers, may identify, but are often formed by symbolic boundaries subject to individual social actors’ conception of differences and similarities that are hard to pin down. Who I present my research findings to, how, and when, can therefore never be neutral.

Two hours had just flown by. We were in the backyard of a local shopkeeper’s house that doubled as an electronic repair shop. But business was closed today. The heavy wooden doors and windows had been bolted shut so no one could interrupt the interview.

The conversation was about two communities entrenched in a bitter battle over ethnic hierarchy in a village in rural, western Nepal. Engrossed by the interview, I had deliberately been doing very little talking when my speaker, a local schoolteacher and youth activist, asked me:

“I have told you everything I know. And I am sure you have interviewed them too, right? Now tell me, honestly… do you think we are telling the truth, or do you believe in their story?”

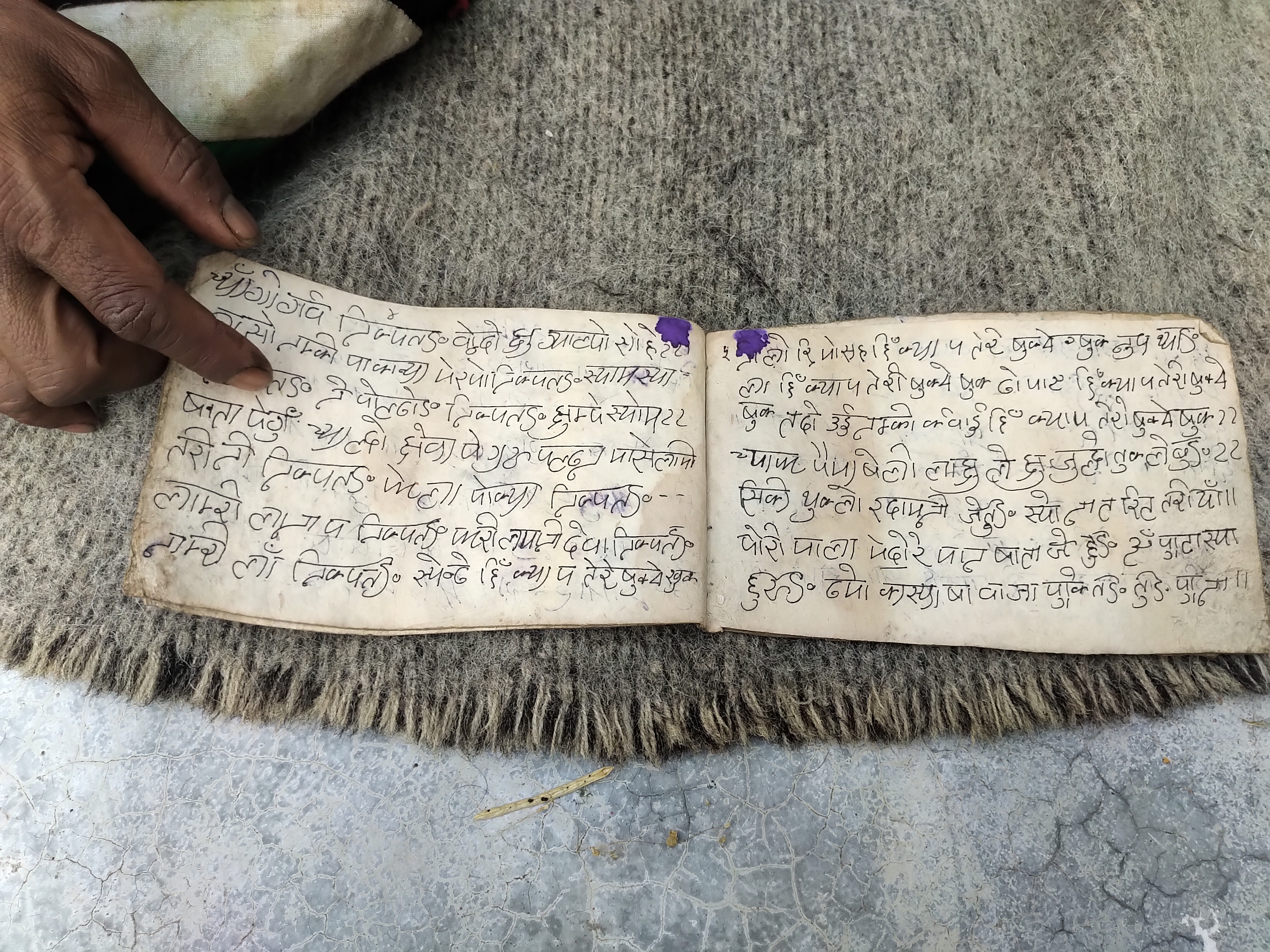

Religious text with unknown scripture claimed by both communities. Picture by Ankita Shrestha.

I suddenly realised at that moment that I had lost my grip over the interview. In a quick turn of events, we had switched roles. And I was now being asked to pick a side.

How should a researcher respond to such a question? Should she answer honestly, knowing that she will be showing researcher bias? Or should she refrain, and explain to her research participant why she must remain impartial?

No matter which way you go, your ethical responsibility as a researcher is challenged.

I was not the first person to be put in that situation. Academics like me had brought their research to these communities before, and they had chosen to be forthright about what they knew. But their answers had led to devastating consequences.

The two communities had been torn by arguments, fuelled by published research findings, over whose language mattered, and who therefore should get the indigenous status from the state.

The feud had become generations deep. Huge political resources had been mobilised to control land, water, and forest resources by either side, and many court cases had been fought. Some conflicts had been physical, violent, and far too regular, mostly among young men, with grave consequences.

The rift had caused the two communities to desperately put together historical and cultural markers that proved their indigeneity over the other community. Political leaders who had rubbed shoulders with these academics had won elections, their egos buffed by such intellectual alliances. And people from both sides went to great lengths to win favours of researchers like me, struggling to maintain the guise of impartiality.

Taken off guard, at the time I dodged the question, but the question of what I should have done remains with me.

Public junction in the village where the young and the old gather. Picture by Ankita Shrestha

I had to revisit this quandary recently, when I was asked to think about what sort of benefit-sharing practice my doctoral research could engage in. Was I considering how I would give back to the community I had engaged with? What would that entail? How about sharing my research findings with the community, not just as a good research practice but as a fair benefit-sharing activity?

That this exercise was part of an ethics fulfilment for my funding organization did not provide any relief. My consternation actually grew as I started to think systematically about what benefit-sharing would mean for my research project.

Of course, corroboration is the mark of any empirical research, but benefit-sharing is more than just checking data for falsities. A key assumption of benefit-sharing in research is that research participants are implicated in making knowledge, that is to say, they are empowered to give content and shape to research findings, and that this knowledge should be shared with the participants or the larger community who took part in the research as a matter of fairness, reciprocity, and transparency.

It sounds like a no-brainer at first. After all, you owe it to your research participants to share what you have learned from them, as this knowledge is neither exclusively theirs nor yours anymore.

But there is more.

The developmentalist aspect of benefit-sharing, more often than not, imagines a power imbalance between the researcher, who generally hails from a more prosperous country, and the community of the poorer country, which needs to be rectified. This thinking is fundamental to the assumption that research findings must somehow be as equally beneficial for this ‘community’ as it is for the researcher.

One must also imagine the community as a static space where research findings can be ‘taken to’ and circulated evenly. And lastly, and perhaps more importantly, one must assume that research findings can, in themselves, be politically neutral, and that both in the act of being shared with the community and in the act of being received by them, this knowledge must remain apolitical. My work casts doubt on all these assumptions.

Children playing in a ruin in a rural abandoned area in the village. Picture by Ankita Shrestha

So, could I take my research findings to the community for the sake of benefit-sharing? The straightforward answer is no.

To say that sharing research findings caused the feud between the two communities I describe earlier would be a gross oversimplification. There certainly isn’t just one matter-of-fact way of sharing research findings; tact and nuance play enormous roles in research processes. And surely, findings can be anonymized to safeguard research participants from any potential harm.

But my concern is not with maintaining confidentiality in research findings or using tact in delivering them. My concern is with the taken-for-granted assumptions of the benefits of sharing research findings and its implications for my research project.

To begin with, the communities I engage with are not far removed from the social-political context that forms my worldviews. My positionality as a South Asian scholar conducting research in South Asia disrupts the very status quo of ‘charitable’ research ethics based on the north-south divide.

Besides, most social science research is not done for benevolent outcomes – any misgivings about the role of research in bringing solely positive consequences must be abandoned from the start if one is to engage in empirical research.

But more importantly, the community or communities in question are not a conceptual monolith. Communities are not always formed by the social boundaries that we, as researchers, may identify, but are often formed by symbolic boundaries subject to individual social actors’ conception of differences and similarities that are hard to pin down.

Who I present my research findings to, how, and when, can therefore never be neutral. Our research, from the start, relies on subjective experiences of each individual involved, including the researcher herself, to weigh in on our findings. We are constantly ‘managing’ people’s truths, making sense of social and political phenomena and the meaning people bring to them. We depend on our interpersonal relations with our research participants and communities that are often forged before we have even asked the first interview question and long after the thesis is submitted. Our research processes are anything but raw, objective forms of truths; we interpret what we observe to create an understanding of what we are researching and what we are faced with.

Construction site of an unfinished memorial building and a local school ground with community forest in the background. Picture by Ankita Shrestha.

Our research participants need to be given the same cognitive advantage we allow ourselves as researchers. Our research findings will be open to interpretation for communities, and we must allow that we may have no control over how it happens or to what effect.

And, perhaps more importantly, just because my research findings may benefit me, it does not automatically mean that it will benefit everyone in the community. The ethical disguise of benefit-sharing may distract us from the actual task of appreciating how it may also affect people negatively. Granted, my research was possible because of the generosity of my research participants and the trust they had put in me, but would it really be fair to foist my research findings on them and assume they wanted answers for the questions they did not ask? And what about the questions they did ask?

***

Ankita Shrestha is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie WEGO-ITN PhD research fellow at the University of Oslo, who has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 764908. Her doctoral research explores concept of the political subject in Nepal.

Brilliant !