By Tara van Ryneveld

Digitalising public services is seen as the sustainable future for Swedish cities but it risks increasing inequality through leaving parts of society behind.

It was late at night and my fingers fumbled on the cracked touch screen of my smartphone as I purchased my ticket. When people ask what I like best about living in Southern Sweden, my usual answer has been the reliable and extensive public transport system. Back home, in South Africa, the train journey to university should have been 20 minutes but my commute was regularly 2 hours long because of train delays. The phone lagged, lazy with the cold before flashing a warning sign that its battery had dropped to below 20%. Amidst the anxiety of potentially not being able to purchase a ticket, my mind jumped to bigger issues: the housing crisis, the rising homelessness and the marginalisation of immigrant and Roma populations within Sweden. How do service providers expect public transport users to all have smart phones, that are charged and have data, in order to use their apps?

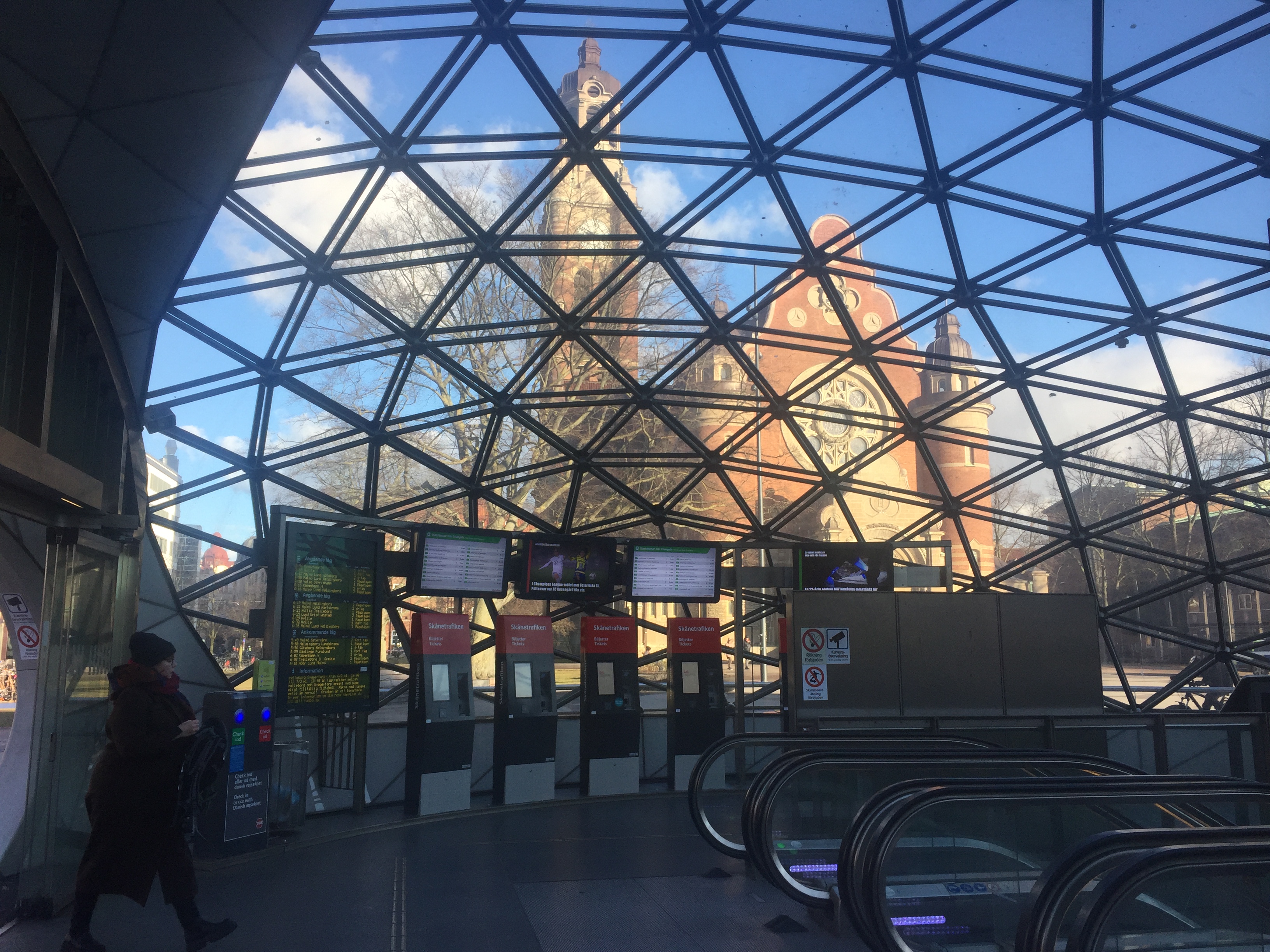

All around the world, a digital shift is framed as inevitable; a future-oriented and positive development. In December 2019, the regional public transport system, Skånetrafiken, phased out the physical travel card that has been part of the traffic system since 2009. Paper tickets can still be purchased at stations, but multi-day tickets and most discounts are only available through the app.

Picture by the author.

The digital city has become synonymous with a sustainable future and Nordic countries are poised as leaders in this shift. Digital technology unlocks huge opportunities, such as open access software, the digital sharing economy, or digital data- informed decision making. Digitalisation claims to make cities “smarter” and more environmentally friendly, control consumption and carbon emissions, for example through data-informed management of excess urban energy and water use. We are told that digitalisation improves the quality of life for residents by making government services accessible, while making it easier for governments to monitor their progress on targets using digital data. But as this trend continues, it is crucial to question whether increasing digital reliance is always the sustainable solution. A Political Ecology perspective can more clearly reveal the winners and losers of digitalisation at both global and local levels.

Internationally, the digital shift and increasing demand for electronics has placed pressure on mineral resource extraction in areas where scarce trace minerals can be found, such as in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Critical geographer, Philippe Le Billon, has unpacked extensively the exploitative practices of resource extraction that trigger and rely on violent conflict, political instability, human rights violations, and unregulated mining. Simultaneously, planned obsolescence and a market geared towards encouraging consumption produces large quantities of electronic waste that are shipped around the world and processed out of sight of the privileged consumer, with environmental and health implications for those exposed to that waste. A shift to increasing reliance on digital technology cannot claim to be the sustainable path forward when it relies on the externalisation of environmental impacts through the dispossession of land, natural resources and the marginalisation of communities involved in extracting minerals and processing discarded electronics.

The “digital divide” by Oliver Lavery is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Within Sweden, digitalisation of public services may superficially fulfil the sustainable “smart” city dream, but it also increases social marginalisation. Public transport is central to sustainable transport within cities. More fundamentally, it historically has enabled access to resources and opportunities, especially for those without private transport means. In theory, it is a great equaliser, enabling vulnerable and marginalised segments of the population to access the benefits of living in a city. The digitalisation of Skånetrafiken’s transport system relies on an exclusion of certain public transport users. In a press statement announcing the discontinuation of the old physical travel cards they point to smart phones and the digitalisation of society as changing their customers’ needs and demands. Their underlying assumption is that all customers have smart phones. But this is not necessarily the case.

In Sweden the digital divide still exists, separating society into those who have easy access to the digital world, and those who don’t. Accessing the digital world is hindered by where a person lives, their class, age, gender, health and migration status. In other words, those who are already vulnerable and marginalised in society are likely to experience barriers to accessing digital technology. Digitalising public transport does not consider those who cannot afford or use a smart phone to access this public good, making it harder for individuals from marginalised and vulnerable groups to access resources and opportunities that rely on public transport use.

“Smart City 2013” by FPA S.r.l is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0. From Flickr.

This development needs to be viewed in the broader context of growing nationalism and the rise of social inequality within Sweden. The framing of Skånetrafiken’s customers as smart phone users raises the question of who the Swedish public services are prioritising and catering for, and by extension, who are considered legitimate parts of the Swedish society. The Swedish history of increasing rights and egalitarianism is at odds with the fact that this public good is not targeting the vulnerable and marginalised segments of society. Instead, the movement towards digitalisation is increasing marginalisation through structural means of those who are implicitly viewed as “other” by Swedish society, contrary to the country’s marketed ideal of a society open to everyone.

As the world moves towards greater digitalisation and smart cities become the normative pinnacle of achieving sustainable development, it is crucial that we consider how this is perpetuating capital accumulation by the wealthy. It is dispossessing the marginalised from resource and opportunity access locally, and furthering marginalisation and inequality globally, where extraction takes place and environmental and health costs are externalised to. While there are definite benefits that come with digital technology, who are these benefits designed to be for? And should we move to digital technology because it is portrayed as inevitable, without debate? Is it always the right answer? Or is the “smartness” of our sustainable cities blinding us to the social and environmental impacts of a digital transition?

—

Tara van Ryneveld is a South African student, currently completing the Environmental Studies and Sustainability Science (LUMES) program at Lund University, Sweden, thanks to a Swedish Institute Scholarship.