By Rebecca Elmhirst.

Feminist Political ecology is becoming a more pluralized set of knowledges and practices, where feminist and environmental social movements and professional practice are changing the kinds of questions being asked and the ways that we work. What does that mean for political ecology and its pedagogies within the academy?

This post is based on the author’s Welcome Address in the 10th Dimensions of Political Ecology (DOPE) Conference, held at the University of Kentucky (USA) and organized by the Political Ecology Working Group, in February 2020.

Introduction

Much has happened to shape the amorphous being that is political ecology over those 10 years since DOPE’s first meeting. Political ecology is probably even more multi-dimensional than when that first group of grad school political ecologists got DOPE under way. Where has political ecology been since then? Looking at the schedule here and the range of excellent, timely and important research being showcased is enough to demonstrate that political ecology has grown even further to be an expansive and open-ended field that embraces and contributes to diverse theorisations of social relations of power associated with natures, culture and economies.

Its geographical reach is more polyvalent than ever– an emphasis on the global South has long since given way to more complex geographies that demonstrate the power of political ecology approaches for tackling environmental injustices in our own cities and neighbourhoods. Furthermore, engagement with decolonial and anti-racist politics has tuned political ecology in, if not resolved, its inherent issues with white colonialist privilege and epistemic violence.

I see in the papers for this conference, just as I see in the sub-discipline as a whole, a shared commitment to activist scholarship: to challenge conceptions and practices of knowledge and authority that do harm, and to undertake our work through engaged research and pedagogies that keep analyses of power at their centre, but carry a spirit of hope for better ways of living together in a multi-species world.

More than ever, this kind of work is needed, when we are faced with myriad wicked problems and very troubling politics, and here I speak from Britain – with a government that courts far right extremism, racism and eugenics (look at the reading list of the prime minister’s special advisor).

Here I advocate for going “Beyond the handbook” and for “Pluralising the practice of feminist political ecology”. What this means is that rather than present a ‘handbook’ stocktake of currents in feminist political ecology and leave it at that, I’m going to augment this by probing at the edges or boundaries of this subdiscipline, and in particular, around the ‘doing’ of FPE. I offer a situated account of the ways I see an ‘undisciplining’ taking place that is attentive to the myriad roots into FPE.

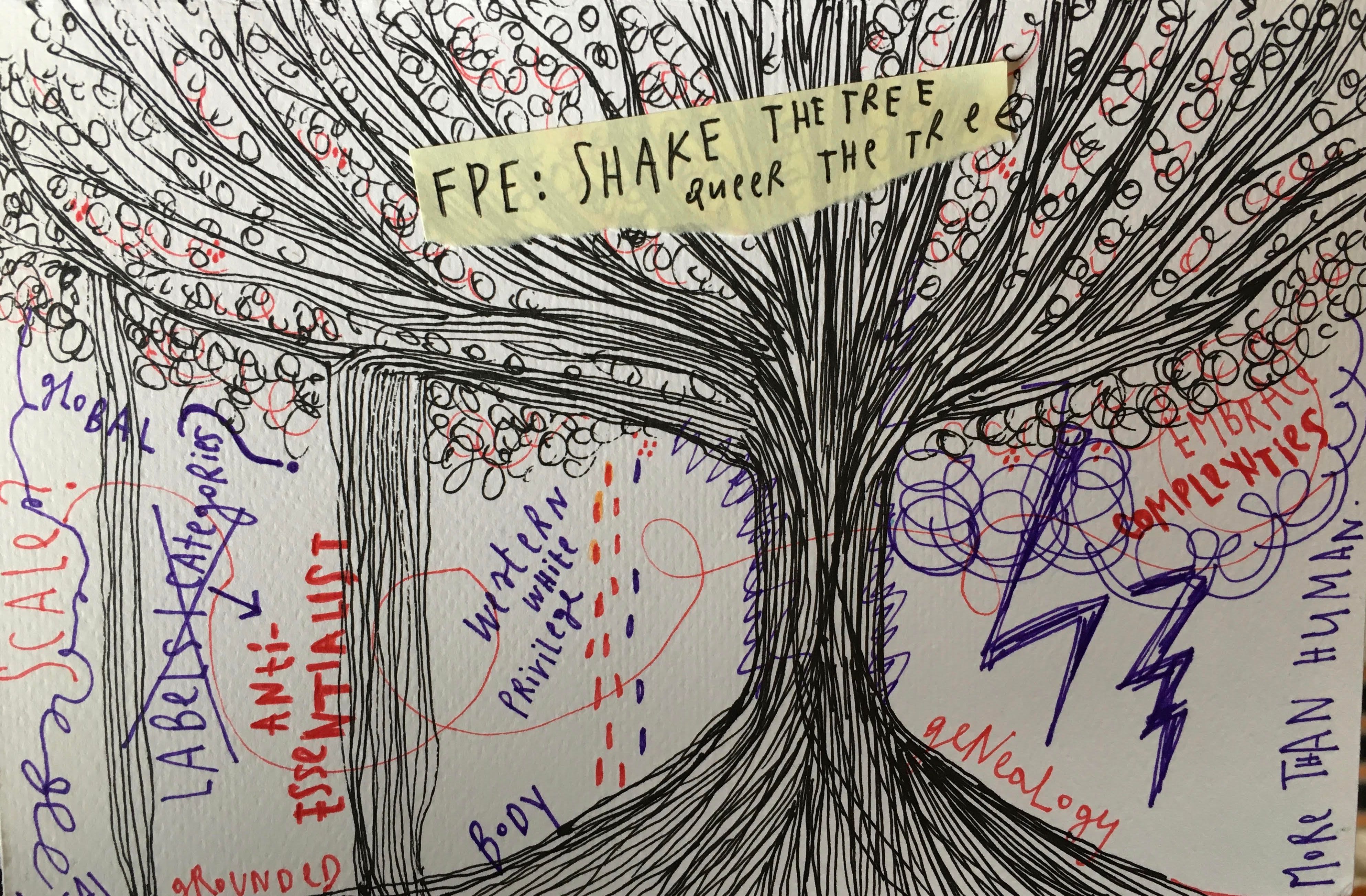

My feminist tree in a feminist forest: a tree with merging branches and roots, that I can water, shake, narrate, watch blooming and transforming, in a forest full of diverse and companion trees.” Drawn by Irene Leonardelli, during the WEGO online training lab in June 2020.

Troubling the Practice of Discipline-making

Whilst FPE embraces a diversity of approaches and subject matters, there is a shared (if often implicit) commitment to feminist epistemology, methods and values, where dominant, masculinist conceptions and practices of knowledge and authority are recognised and challenged, and where emphasis is given to research and practice that empowers and promotes social and ecological transformation for women and other marginalized groups.

Some years ago, I was moved to convene a special issue with the title ‘New’ feminist political ecologies, based on a panel at a commons conference from a couple of years previously. I had been frustrated by the way that research in feminist political ecology – which struck me as incredibly rich and interesting in bringing new political subjectivities into the frame – was not very visible within an emerging PE cannon. As PE textbooks were churning out, it seemed all too easy for FPE to be referenced away by the citation of one or two key authors, but no substantial engagement beyond that. My reflection at the time was about why that might be, and the special issue was my attempt to bring together and make visible to a wider PE audience research and researchers that were inspiring for me, among them Andrea Nightingale, Farhana Sultana, Yaffa Truelove, Bernadette Resurreccion. Somewhat unreflexively, I had unwittingly and unthinkingly used my privilege to make a ‘canonical move’ that was situated and rooted in rather specific ways.

Is FPE a canon? Should it be? As James Sidaway has noted for my companion discipline of Geography (Sidaway 2018), FPE is structured by canonical concepts and enduring practices rather than many long‐lasting texts or authors who are still being widely read long after their retirement.

Whilst FPE embraces a diversity of approaches and subject matters, there is a shared (if often implicit) commitment to feminist epistemology, methods and values, where dominant, masculinist conceptions and practices of knowledge and authority are recognised and challenged, and where emphasis is given to research and practice that empowers and promotes social and ecological transformation for women and other marginalized groups.

Handbook entries and review articles (of which there are many) represent efforts to map out the terrain of Feminist Political Ecology, and rather than intentionally making canonical claims that highlight particular authors, they flag particular concepts and practices. However, the debates that have followed demonstrate the situatedness of knowledge claims that these kinds of mapping exercises involve, and the route into FPE taken by the author. Moreover, omissions and inclusions may unintentionally present forms of epistemic violence that those writing from FPE are otherwise seeking to confront.

Undisciplining Feminist Political Ecology

Recovering my reflexive compass, I can say that as a white anglophone academic feminist political ecologist, writing from the perspective of critical development studies, my own stock-taking reviews have emphasised work in FPE that relates to empirically-driven debates around dispossession, resource access and control in global South contexts (see for example my entry in the Routledge Handbook of Political Ecology) and therefore reflect my engagement in specific transnational networks of thought and practice in FPE.

Others narrate feminist political ecology from somewhat different networked positions, as highlighted for example, in the collection edited by Wendy Harcourt and Ingrid Nelson, which gives greater emphasis to FPE as “a process of doing environmentalism, justice and feminism differently”, including through engagements with queer and post-humanist ecologies (Harcourt and Nelson 2015: 9).

Furthermore, handbook contributions by scholars like Sharlene Mollett (in the Routledge Handbook of Gender and Environment) and Juanita Sundberg (in the International Handbook of Political Ecology) respectively are explicitly engaging critical race theory and decolonial thinking to challenge hegemonies of white, Anglophone, colonial, Western knowledge practices and politics (Sundberg 2014), and in doing so have opened up more radical possibilities for engaging with power and other world views, and other ways of knowing, thereby bringing other kinds of networks of thought and practice into conversation with FPE.

Outside the Anglo-North American university system, other ‘handbook’ stock-takings of feminist political ecology are being written, which take yet another slice through academic publications that claim the label of FPE, and that are animated by other transnational networks of scholars, activists and practitioners, including those who are part of the Undisciplined Environments network, which grew out of an EU-funded networking project led from the Autonomous University of Barcelona called ENTITLE. The term ‘undisciplined’ has been chosen by the group deliberately to decentre academic authority in ‘canonising’. Undisciplined Environments network is now linked to another European funded network project, modelled on the same basis, but with an explicit focus on feminist political ecology, and in ‘training’ the next generation of scholars in this field (funder perspective), with which I am involved, WEGO (wellbeing ecology gender and community).

WEGO was conceived by bringing together different people with various degrees of commitment to FPE, anchored in nodes in various European universities, but with networks spanning into academic, activist and practitioner fields across the world. The project has been consciously and reflexively operating along the lines of ‘rooted networks’ (see the work of Dianne Rocheleau). Our politics and ethics mean we have been trying to do FPE ‘otherwise’, but as a ‘training network’ for graduate students, we have sought to think through how we embrace FPE as an epistemic community. The agentic force of pedagogy encourages us to map out debates. There are struggles within the network around this, and disagreement as to whether there is such a thing as a feminist political ecology analysis –which seems to need something else, if it is to mean anything. Yet in thinking relationally and ‘from’ the WEGO network, a (possibly contested within the network) mapping of FPE is emerging in a particular form, and what I notice is that it has very different contours and outlines than the mapping I attempted more than 10 years ago (not long before DOPE was conceived).

WEGO’s work hinges on three interconnected areas that we have so far identified as enriching FPE at this point:

- Impacts of and responses to the related logics of extractivism, enclosure and dispossession in north and south contexts, with an emphasis on body and community, and drawing on conceptual themes such as emotion and affect, gendered and plural ontologies and values accorded to non-human natures; and intersectional power in the politics of access and exclusion;

- Sufficiency/degrowth, commoning and a feminist ethics of care, exploring deeper engagements with situated concepts such as social reproduction, and linking to community; and

- Decolonial feminist political ecology, that tackles epistemic privilege, violence and authority and re-thinks the world from Latin America, from Africa, from Indigenous places challenging universalizing claims that subordinate other ways of knowing.

This renewed iteration of FPE has shifted away from my earlier framings, with their roots in ‘my’ intellectual biography (from critical development studies, via feminist geography, and into FPE).

WEGO’s mapping reflects the project teams’ different intellectual roots in academic turf of community economies and science and technology studies, for example, and from specific social movements: ecofeminist political economy (with its emphasis on degrowth and care, emerging from mainland European austerity politics and Latin American anti-extractivism) and environmental justice movements of the global South, picking up the point that a plural political ecology is rooted in a multiplicity of values and starting points.

Re-weaving Feminist Political Ecology

In concluding my reflections on FPE, what has also been important in WEGO’s network of networks for me has been the learning and inspiration from the prefigurative politics of feminist and environmental justice movements, found in my involvement with extractingus.org, which brings together academics, activists and artists to afford feminist perspectives on extractivism and care, and bringing this into the everyday practice of academia as a space for learning and teaching. Viscerally, this has been felt in the university strike actions that have been underway in the UK, in which we have tried to model the university future we want through practices of care (between staff and students) on the picket line and in teach-outs.

FPE has emerged from earlier gender, environment and development studies, is being enriched by feminist science, technology and society approaches, and is being given a more transformative flavour through strands that originate in environmental justice, anti-racist and feminist social movements. An undisciplined canon in the making.

Note: You can watch the full Welcome Address speech here.

*Rebecca Elmhirst is Professor of Human Geography in the Centre for Spatial, Environmental and Cultural Politics at the University of Brighton in the UK. She is a mentor in the WEGO network and a member of POLLEN. Her research interests converge around feminist political ecology and critical development studies, based on long-term international collaborations investigating displacement and agrarian extractivism in Southeast Asia.