By Luigi Pellizzoni

How can we read and interpret the rise of environmental movements at an age of globalisation and climate change?

In the first part of this essay, I outlined the background of, and significant differences between, the Fridays for Future (FfF), Extinction Rebellion (XR) and Gilets Jaunes (GJ) mobilizations. Let’s now address some common traits.

A first similarity is the radicality and apparent non-negotiability of the basic goal: for XR and FfF it is a matter of achieving ‘zero emissions’ within a few years; for GJ of getting rid of the neoliberal logic of maximizing inequalities as an engine of growth. From this point of view, new movements seem to deviate from the compromise strategy followed for decades by environmental organizations and trade unions.

A second common trait is the framing of the crisis and the way to deal with it, which is that of climate justice, seen as inseparable from social justice (or vice versa, in the case of GJ). As a result, particularly in the discourse of XR and FfF, climate denial is equated with a defence of the social status quo, like two sides of a same coin. That they are correct in making this point is confirmed by how denialism generally claims that the current is the best of all possible worlds, indeed the only possible one, there being neither technical nor economic or political margin to change it. The ensuing blurring of the case for the (im)possibility to affect climate change and the case for the (im)possibility of improving environmental quality and living conditions, in particular of those who do not belong to privileged elites, is precisely what climate justice movements tackle – and would arguably benefit from unpacking. The centrality of the theme of justice in the discourse of new movements confirms a trend that has been underway for quite some time. The frame of ‘environmental justice’ had emerged in the US around 1980, in regard to protests against pollution and health damage in working class ‘black and brown’ communities. The reference to injustice (sometimes in connection with ‘environmental racism’), as a less politically loaded concept –at face value, at least– than inequality, exploitation, or class conflict, can be explained to a significant extent by taking into account how the United States’ political culture is by tradition largely alien to a strong ideological conflict concerning capitalism. However, the meaning of environmental justice has subsequently expanded to encompass, in a much more politicized sense, the systemic forces in capitalism that generate injustice, and the relations between the global North and South. It is therefore this frame, where ‘environment’ and ‘climate’ are now largely synonymous, that links the mobilizations we are talking about, which concern the affluent West, with those of Latin America, Africa and Asia, where it is mixed with a critique of corporate neo-colonialism and the defence or recovery of indigenous ways of life as forms of opposition and resistance.

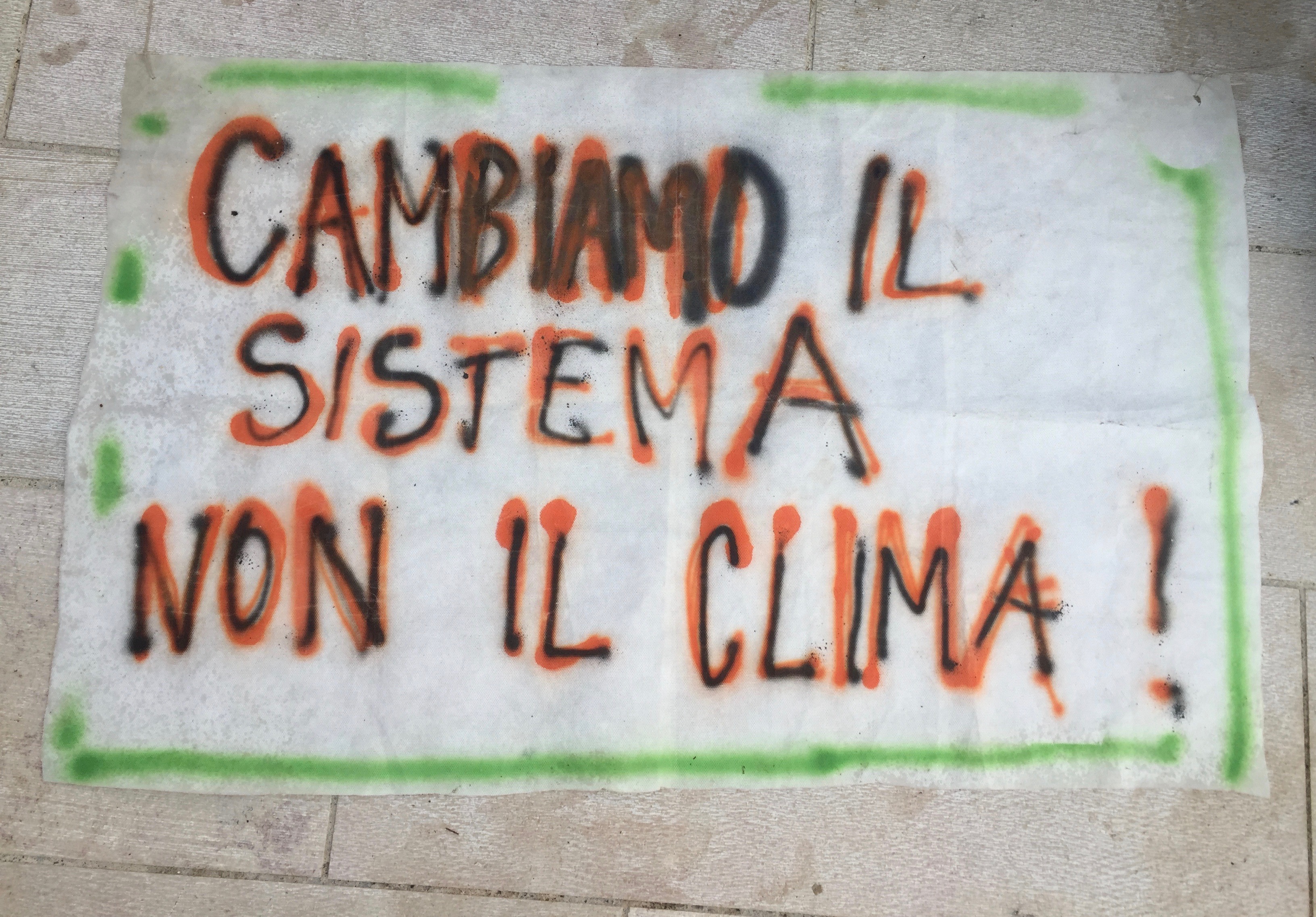

The framing of the climate crisis as a social justice issue links to the historic trajectory of environmental justice movements since the 1980s. Photo by: Maura Benegiamo.

“The end of the world, the end of the month. Same struggle!”, a sign in a Gilets Jaunes demonstration, reflects this linked framing. Photos by: Maura Benegiamo.

A third similarity of these three movements was also a key feature of other recent movements, such as Occupy Wall Street: the absence of precise specific policy requests. For both Extinction Rebellion (XR) and Fridays for the Future (FfF), the goal is decarbonisation, and what they demand is a more incisive intervention to achieve it. However, there is no detailed indication of which are the solutions to adopt. For Gilets Jaunes (GJ), the goal is a redistributive turn of policies, but even in their case it is difficult to discern a precise programmatic line. Before solutions, their very demands made by GJs are for a good part generic, sometimes contradictory and arguably impossible to pursue all together. For Occupy, the absence of specific demands was integral to a strategy aimed at denying legitimacy to governmental forces. This does not seem to be the case with GJ, XR and FfF, who, rather than aiming to delegitimize established powers, want to see them marking a change of pace and strategy. In this way, the generic nature of the claims becomes a weakness. Greta’s detractors have an easy game in pointing out how what FfF activists are asking for would imply a downsizing of the lifestyles they are used to, and which constitute a condition of possibility for the movement itself, beginning with its transnational scope. Consider mobility, whose value for the sake of reciprocal acquaintance and dialogue between peoples and cultures is unquestionable and from which the ‘Erasmus generation’ has particularly benefited. Going to New York on the sailboat of Pierre Casiraghi – heir of the Principality of Monaco, that is a cradle of greedy capitalism, the opulent lifestyles of the super-rich, and excessive urbanization – does not indicate any viable solution, but rather highlights the contradiction in which FfF fall when moving from words to facts. Also, the technologically advanced, eco-friendly character of the sailboat can hardly be made to fit smoothly with a case for climate justice (see below), if not at the price of forgetting the backstage of social and environmental imbalances and inequalities on which frontstage technological wonder is built.

Fourth common trait: the lack of referents in the current political spectrum, neither in traditional parties nor in new political formations such as the Italian 5 Stars (whose engagement with GJ was almost immediately aborted), even if contacts with extra-parliamentary groupings are significant. A fifth affinity between XR, FfF and GJ concerns a distrust of do-it-yourself environmentalism, individual goodwill, everyday life engagement, the art of getting by; and this for both its eventual ineffectiveness and the inequalities it implies and produces. Thus, at least in part (see below), new mobilizations show signs of a rejection of market-mediated ‘responsible individualism’ (as in ‘green consumption’), on which not only governments but also many scholars have put major expectations.

A last but fundamental common trait of these new movements is their diagnosis of the present, marked by a sense of imminent social and ecological collapse. The idea is that collapse is near, perhaps inevitable, yet could at least be mitigated or made more manageable if drastic actions were undertaken right now. This is explicit in the case of XR and FfF, emphasizing that we are in a (climate) ‘crisis’ and ‘emergency’ where ‘time is running out’ to save our planet and humanity, since ‘there is no Planet B’. In GJ this collapse is implicit in the way demonstrations of largely peaceful and not very politicized citizens easily turn into bloody battles. In some countries, such as Italy, collapsology has not yet gained strong public salience; elsewhere, such as in France, a conspicuous literature, partly scientific and partly popular, has piled up, as have discussions in social networks. Catastrophism, however, is not just a reaction to pressing events, such as the Swedish fires in summer 2018 (which partly gave rise to Fridays for the Future) or the impoverishment of the lower middle class (which partly gave rise to the Gilles Jeunes). It is integral to the rationality of government that has increasingly taken root with the spread of neoliberal culture and regulation. A vast literature documents how preparedness (as readiness to react to the unexpected) and resilience (as the ability to respond to traumas by reorganizing on new bases) are more and more insistently promoted at the individual, corporate and social levels. This is done on the basis of the assumption that equilibrium, order and predictability are not the norm but a transitory exception and that therefore, for each and for all, the task is learning to ride the unpredictable and manage the ungovernable. If we consider new movements from this point of view, then, they result less innovative and radical than it might seem, as they fail to question the worldview and the existential horizon that intellectual, political and economic elites have imposed in the last decades. Said differently, the issue is whether a system that thrives on the threat and the actualization of catastrophes of any sort and size (from Wall Street to WW2, from 9/11 to humanitarian wars), can be challenged on its own terrain, and with the same case for urgency of the bank manager who talks of an investment which ‘won’t remain so profitable for long’.

A “Productivism = death” sign shows the links between a critique of the economic model and the climate crisis in some sectors of the movement, while also suggesting a catastrophist frame. Photo by: Maura Benegiamo.

In Part 1 of this essay, I talked of the double impasse of climate action, from above (failure of elites and market-based economy) and from below (failure of individualist consumer actions), as a spark from which the fire of new mobilizations spread. However, there is probably another one, of which catastrophism is a clue. This is the sensation – which the young and the lower classes of the North, coming from an affluent past, feel more acutely than their homologues of the South, that the future is ‘stolen’ first of all by technology, in the sense of the latter’s eventual inability to provide the driving force that would be now absolutely necessary, from both a social and an ecological point of view. The impression, in other words, is that, before and beyond an actual collapse, the spectre that haunts new mobilizations is the ‘great stagnation’. Admittedly, this is a counterfactual claim, as FfF and XR distinguish themselves from ‘technophobic’ strands of environmentalism by claiming how technology, if taken off the hands of capitalist elites, offers plenty of possibilities beyond timid, and job-eating, mitigation of, or adaptation to, climate turmoil. Yet it is precisely the combination of catastrophism and the full opening towards technology that sounds somewhat out of tune. Why would elites stubbornly proceed towards disaster, if they had effective technologies at hand? Do the movements think the elites are like the Titanic’s first-class passengers, grabbing the few lifeboats available and letting the others sink? Can the elites really dismiss how an ecological catastrophe and the rebellion of masses with nothing left to lose would not leave them any safe land to reach?

The reflections proposed in the two parts of this essay have a schematic, provisional character. We are too close to the events to be able to evaluate them with adequate detail and clear-sightedness. The movements discussed are evolving quickly, and they already show substantial diversity across countries. We shall see. There is no doubt, however, that the mobilisations begun in 2018 show peculiar, if not easily decipherable, features. A major question is how they will respond to the reformist season announced under the Green New Deal heading, which their actions have fostered. Answering is impossible at the moment, also because there are different interpretations of the Green New Deal. Some are aimed at giving renewed centrality to state intervention, as with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s neo-Keynesianism. Others, as it seems the case with the incoming European Commission, propose a refurbished edition of the green economy. And still others see the GND as a wholesale transformation of the economy, with democratic ownership of the means of production, and focused on doing justice to the frontline black-brown-indigenous communities historically affected by extractive forces. Therefore, it is difficult to predict if the Green New Deal, in whatever version, will be something more and different than a revival of ecological modernization, in more dramatic historical circumstances.

“System change, not climate change” has become one of the main slogans of the new mobilizations. Another sign reads “If the climate was a bank, it would’ve already been saved”, making reference to the hypocrisy of elites inaction on climate change, compared to the bank bailouts post-2008. It remains to be seen whether the trajectory of the movements will continue this radical (systemic) approach, or a more reformist one. Photo by: La Stampa

The trajectory of these movements will in part depend on the answers given to open questions. What does it mean, for example, to trust science and technology? Is FfF restating the idea of their neutrality with respect to power and interests, in spite of decades of opposite evidence from science and technology studies and, before these, of ever timely reflections of Adorno, Benjamin, Marcuse and the like? Can the planetary success of Greta, and the fact that the most exclusive doors have opened to her, be explained (also) because she offers a clean face to global capitalism’s attempt – which Casiraghi’s sailboat vividly expresses – at governing the technological transition to reaffirm and strengthen itself? Faced with these questions, an important testing ground for new mobilizations, for their role in the ‘change of route’, will be their attitude towards science and innovation; the ability to imagine and stimulate a qualitative leap in the way the goals of both, their relationship with power and with the human and the non-human, are set and enacted.

Another open question is how FfF, XR, GJ and other emerging movements are going to deal with the problem of collective action. On the one hand, as we have seen, these mobilizations seem to revamp the traditional political protest; on the other, a recent study of the Fridays for the Future mobilizations suggested a persistence of the idea of do-it-yourself environmentalism (i.e. that ecological transition has to build first of all on individual lifestyle changes), albeit with marked differences across countries and age cohorts. On this, it is early to say whether there will be a convergence or else a sharp divarication in what presently appears a plural yet somewhat coherent social effervescence. It is clear, however, that an evolution in the one or the other direction will be relevant to the broadening or shrinking of the scope of mobilizations and their support to ‘strong’ or ‘weak’ versions of the Green New Deal.

Luigi Pellizzoni is professor in sociology of the environment and territory at Pisa University (Italy). His interests focus on environmental issues, the impacts of technoscientific advancements, social mobilizations and the transformation of governance. His latest book is Ontological Politics in a Disposable World: The New Mastery of Nature (Routledge, 2016).

One Comment