By Emma Lord*

On December 1st, 2016, headlines marked the formal end of Colombia´s prolonged war. Emma Lord shares some reflections on the contextual complexity of the conflict based on fieldwork in the department of Valle del Cauca in 2015.

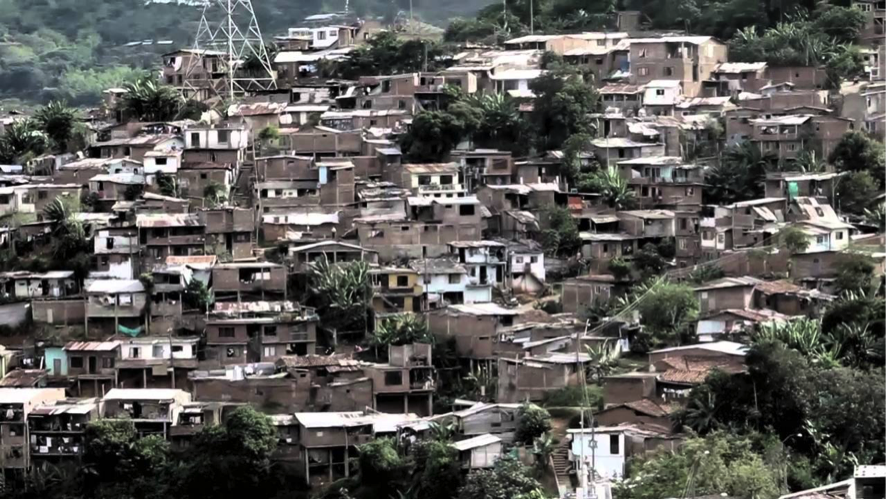

Siloe neighborhood, Cali, Colombia. Source: Radio Macondo

Sitting in the kitchen of a caleño guitarist –a research informant and friend– we chat about his day over fruit salad and scattered documents, reproduced paper forms on the table. We just recognized each other in the street, two blocks from his house, from regular gatherings to recite and share poems in a local park. The meeting was coincidental as he was returning from his dusty bus transit to a satellite town on the foothills of Valle de Cauca, two hours from Cali. The documents we look at are from his land restitution claim under Colombia’s Ley de Víctimas y Restitución de Tierras (2011), which aims to compensate victims of the armed conflict since 1985. It is October 2014.

As a European researcher interested in tracing the concrete processes governing access to land, I am curious to follow the details of my friend’s procedure as he prepares to return in two months or so for his next appointment. Thanks to his poems, I already know the story of his son, exiled in Canada; and his final words to his deceased wife when they parted ways on the journey to Bogotá, her by plane and his by night bus, due to his last-minute premonition against flying that night, dismissed by her as superstitious.

Who says my poems are poems?

My poems are not poems.

After you know my poems are not poems,

Then we can begin to discuss poetry!

Japanese Haiku, Ryokan; in ‘Amor en la noche, guerra en la mañana’ –Diego Lozano, Caleño poet

Official reclamation points for armed conflict victims within the city of Cali are already beyond their capacity, as the administrative wheels of the cumbersome land restitution process are only just grinding into action. Despite years of planning, international human rights organizations predict that only a small minority of claims can be successful. Given the extent and high level of manipulation inherent in state institutions recording information related to this historically complex context, concrete incidents can be the only means to gauge what is taking place.

Here, even the most supposedly certain of international agreements fails to be respected. For instance, the Colombian constitution of 1991 granted de jure territorial rights to indigenous and afro-Colombian groups, acknowledging the formal basis for a pluri-national politics of difference. The creation of Zona Reserva Campesina (ZRC) awarded rights to non-ethnic peasants in 1994. Nevertheless, legal recognition proved irrelevant in preventing de facto forced evictions from the ethnic territories of the coastal Pacific Rim. And despite the Colombian government’s ratification of the signed peace agreement with the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) in December 2016, my prolonged observations in the Valle de Cauca revealed a much more complex situation. Military forces remain authorized to kill whichever gangs they have labeled as criminal, marking the covert continuation of an unofficial war.

The non-governmental organizations working to facilitate victims’ claims to compensation and land restitution in Cali are much less visible than their counterparts in Bogotá and Medellín; few have websites or publicity on digitally searchable directories. For me, gaining the level of trust and social connections needed to be able to talk to them freely has taken some months. However, with patience, my extended stay brought connections to a nationwide social movement, ´Voz de la Consciencia´, which helped see more clearly through clouded waters (you can listen to their radio station here).

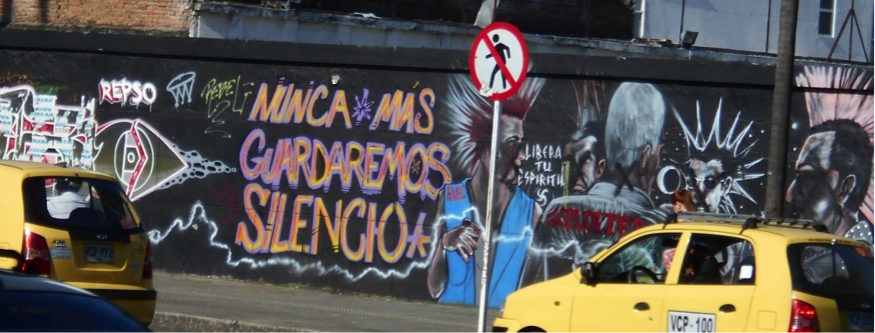

The streets of Cali are alive with murals, rich and anonymous forms of expression. Source: Author.

Displacement is not an officially encouraged research theme in Colombia, yet many intellectuals work now under threat or exile. This created challenges in terms of knowing exactly where to begin my research when I arrived in Colombia in April 2014. For example, one of these intellectuals, Alfredo Molano, has narrated his forced exile to Spain after uncovering a thousand stories of “eviction for political reasons, but for economic ends” as a sociologist and journalist.

Searching through library press records brought much relevant knowledge, but not in the manner I expected. A hushed phone call from an attendant, then a quiet request to present myself to someone that wanted to meet me. Much to my relief it was an offer of assistance from a gentleman under early retirement from the university. Through his patient narrations, my understanding about the areas with unrecorded narratives grew. His stories contained rich details and opinions, missing from many historical accounts of Colombia. I gradually realized how widely different the printed word can be from what Colombian writers would like to express, if granted freedom of speech. What is set in print can be often evocative yet at times rather cryptic.

For me, the most vivid anecdotes came from discussions with poets. Talking and listening to them I grasped how to understand Colombia’s history. I needed to consider key authors and events that my previous digitized literature reviews had overlooked. Many poets write anonymously. One of these, for example, opened his soul to reveal the meaning of war; watching the blood drain from his companions’ faces, learning of the destruction of their remains, escaping to wander the hills alone, due to a favor that had saved the life of a military general’s son.

El Lomo (anonymous)

| Hoy desperté soñando, yo no escuchaba el traquetear de la metralleta, en su lugar escuchaba el trino de pájaros lejanos; soñé que los fusiles se convertían en machetes. Que donde se sembraban minas, crecían arboles de pan coger, oí sonrisas de niños, ladrar de perros y robustas mujeres, lavar en los ríos, vi hombres que en vez de mochilas y fusiles llevaban canastos y azadones. Soñé que lo tierra ya no se teñía de rojo, sino verdecid esmeraldina, ya no corrían ríos de sangre, ni de llanto sino cascadas cantarines, vi como blancos pañuelos se elevaban al aire convertidos en palomas. Vi mis viejos, mi rancho, y aquel escuálido caballo que en su huesudo lomo me llevo a la escuela , trotando alegre… Pero desperté a mi oscura realidad Soy solo un pensamiento, hoy mi morada frio, lo comparto con otros seres sollozantes… Me ha crecido hierba entre los dedos, donde habitaban mis ojos, solo hay dos cuencos oscuros y vacios, soy un desaparecido mas. Una estadística, un Jhon Doe, solo espero que algún día escuchen mis silenciosos ruegos, y me sepulten en tierra santa con mi verdadero nombre, pues no me llamo ‘NN’. |

Today I awoke dreaming, I didn’t hear the (click) of the rifle, instead I heard the trilling of distant birds; I dreamed that the rifles had changed into machetes. That where they had laid mines, grew trees of ‘pan coger’, I heard smiles of children, barking of dogs and sturdy women, washing in the rivers, I saw men, instead of carrying rucksacks and rifles bore baskets y rakes. I dreamed that the earth no longer contained red, only green emeralds, no longer ran with rivers of blood or tears, only singing cascades, I saw white handkerchiefs raised in the air changed into doves. I saw my old folks, my ranch, and that skeletal horse that carried me to school on its bony back, trotty happily… But I awoke to my dark reality I am only a thought, today my cold hearth, I share with other sobbing beings… Grass has grown between my fingers, where my eyes lived, there are only two dark and empty holes, I am just another who has disappeared. A statistic, a John Doe, I only hope that one day they listen to my silent prayers and they bury me in sacred earth with my real name, then I won’t be called ‘NN’. |

Who can say how many countless stories about the Colombian conflict remain untold? The illustrations accompanying the impromptu poetry of Cali, printed, hand written and online, depict every facet of human imagination from the beautiful to the strange, the wondrous dream to the nightmare. The Colombian armed conflict is notorious for brutal and bloodthirsty accounts of dismemberment, hanged corpses, false positives. By contrast, my interview with X resembled the destruction of a concentration camp, clinical, dehumanized and cold. This association shifts my entire understanding of the research context and raises questions about the wisdom of legal intervention strategies, in the face of such disrespect for the law and for humanity.

Mural, Calle 5, Cali. “We will never keep silent again.” Source: Author.

Who can say how the formal peace declaration will alter the lives of Colombian citizens from now on? Any account of Colombia surely omits the cultural warmth that is typically found among the people, in and around Cali. Since my first arrival welcoming faces on the airport bus warmly inquired into my background, my family, my plans, simultaneously warning against the perils of straying from my intended trajectory, venturing unaccompanied, or even taking a taxi alone. My first transit from the bus station was accompanied by a kind fellow passenger living a few blocks from my hostel. It has been a shock to unravel how this warmth is built upon the deepest incidence of suffering; to shine light on the images imagined by the poets of Colombia. And to experience how in the face of atrocities, which deliberately remain uncounted, people still reach out openly to take a visitor’s hand.

* Emma Jane Lord is a PhD candidate with the Strategic Communication Group, Wageningen University.