By Felix Krawczyk

Negative emissions are often categorically rejected, yet they can also have emancipatory potential.

In recent years, the commitment to the goal of climate neutrality has been increasingly heard in national and international politics. Climate neutrality or net-zero does not exclusively mean reducing emissions but also includes so-called negative emissions. The removal of CO2 from the atmosphere also plays a prominent role in the Special Report of the IPCC on limiting the 1.5-degree target from 2018.

Almost all scenarios in the report are based on the assumption that enormous amounts of negative emissions are necessary to achieve the 1.5-degree target. Furthermore, they assume that there will continue to be economic growth in all countries, whether in the Global South or North. However, increasing economic growth leads to an increasing demand for energy, making a reduction in CO2 emissions significantly more difficult, if not impossible.

It becomes clear that scientific scenarios do not emerge in a vacuum but implicitly contain value judgments about possible and desirable futures. Negative emissions are usually understood as large-scale and market-driven measures. Nature-based measures, on the other hand, are hardly understood as such. However, they can indeed be meaningful, provided they are in line with biodiversity and food production.

The Community Forest of Teís (Comunidade de Montes Veciñais en Man Común de Teis) in Galicia decided to remove invasive species such as acacia negra, developing community-based techniques to do so. These methods are applied in an environmentally sensitive way, working with the sun’s movement, freeing native trees, and planting and replanting trees to support the habitats of local wildlife. (photo by the author).

Carbon is not equal to carbon

It is often assumed that the carbon stored in forests can be compared to that released by the combustion of fossil fuels. However, this comparison is more politically than scientifically motivated. Carbon in fossil form in a reservoir beneath the earth’s surface is virtually permanently stored. In contrast, biotic carbon in plants or soil is part of an active, short-term carbon cycle.

The combustion of fossil fuels results in previously permanently stored carbon being introduced into the active cycle, increasing the total carbon in the atmosphere, oceans, and land systems. However, the carbon in the active cycle cannot be reduced by natural carbon sinks on timescales relevant to the climate crisis.

This means that negative emissions are essentially not simply a compensation for positive emissions; they must complement, not replace, radical efforts to reduce CO2. Moreover, the large-scale application of CO2 storage methods such as afforestation under existing power structures of patriarchy, racism, and capitalism is likely to exacerbate global and local injustices.

It is often emphasized that negative emissions contribute to delaying reduction targets and maintaining the status quo. However, it should be noted that the concept of negative emissions, as currently negotiated in the form of large-scale afforestation or other technologies, has emerged from a specific interplay of science and politics. And therefore, loosely based on Bini Adamczak, a parallel with Hollywood superheroes is obvious, who act according to the motto: Things shouldn’t get worse, but they shouldn’t get better either.

Similar to superheroes who focus on overcoming immediate threats, negative emissions focus on controlling the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. Even though this one-dimensional approach is now being connected with considerations of biodiversity, questions about land rights, climate justice, and a different future are usually avoided. However, an emancipatory potential of negative emissions can be identified through examples of collectively managed forests.

Forests as Commons

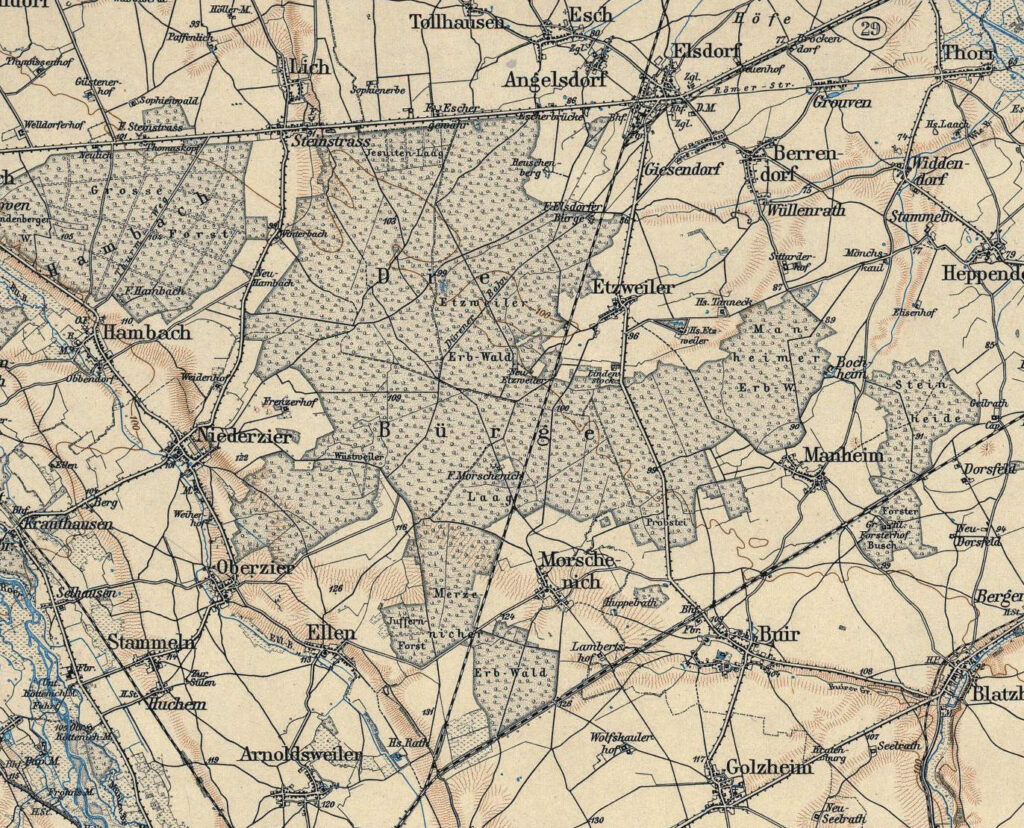

In Europe, forests and pastures were commonly managed in the late Middle Ages and early modern period. In the German-speaking world, this often took the form of so-called wood courts or forest courts. These courts were convened several times a year to self-manage the affairs of users regarding forests, water, and pastures. With the advent of capitalism, forests and pastures were gradually – often violently – transferred into private ownership (see primitive accumulation and accumulation by dispossession).

In the struggle for the Hambach Forest, activists have invoked this narrative of the forest as a common, which is now referred to as commoning. This process is described on Wikipedia (also a common) as “self-organized and needs-oriented collective production, management, care and/or use”.

In contrast to conventional models, where forests are often seen as resources to be extracted and commodified, the concept of commoning emphasizes shared responsibility and care for these vital ecosystems. Commoning thus also questions the capitalist logic of exchange, competition and ownership by anticipating new solidarity-based relationships – i.e. practicing them on a small scale.

Examples of initiatives in Berlin, Scotland, and Spain that focus on the communal management of forests can thus be described as grassroots climate engineering or grassroots negative emissions. Their use contributes to the storage of CO2 while simultaneously establishing solidarity-based relationships and actions.

The Kilfinan Community Forest in Scotland explicitly addresses their contribution to the climate crisis and, a few years ago, hosted a delegation of indigenous Forest Defenders who oppose the destruction of the rainforest in the Amazon as “Guardians of the Forest”. The community around this forest refers to the large-scale eviction from the Highlands between 1750 and 1850. At that time, the tenants and farmers were evicted from these lands to expand more profitable livestock farming.

The initiative Freiwald e.V. pursues a similar approach in Berlin and aims to acquire areas to afforest them. This is intended to withdraw ecosystems from the market and ensure their stability. The trees for the project come from a tree school that works according to the principle of community-supported agriculture.

And finally, from 1995 onwards, in connection with protests against a planned highway in Teis, a small town in the Galicia region, the form of commons ownership has been rediscovered. The special thing here is that the activists did not stop at criticizing a state project but were able to mobilize a powerful concrete utopia.

While the construction of the highway could not be prevented, the commoners manage and care for their forest themselves. Commoning also contributes to direct interaction and a caring restructuring of the human-nature relationship.

Examples of such changes can also be observed in forest occupations. Knowledge about mushrooms, herbs, and plants is exchanged. During the occupation of the Dannenröder Forest in Germany, activists collected pieces of wood from the trees they occupied. Other activists gave names to the trees like “Grandpa”, “Grandma”, or “Grandchild”, illustrating the unique relationship between them and the forest.

The forest as a commons—this was the narrative invoked by activists in their struggle over the Hambach Forest. Photo: Wikimedia Commons/hambinfo.

Social Revolution?

These examples can be seen as elements of a social revolution. This is usually understood as a reordering of all areas of life such as culture, politics, economy, ethics, gender relations, and human-nature relations. While the superhero wants the world to remain as it is, the social revolution involves a collective learning process and changing fundamental relationships in society and with non-human nature.

Unlike the widespread understanding of revolution, the social revolution does not happen abruptly but is understood as a process of practicing other actions and relationships. In other words, negative emissions and revolutionary change are not mutually exclusive. Because both can be connected under certain conditions, and even after a hypothetical upheaval, ecosystems must somehow be managed. In order to avoid falling into old patterns, we can start practicing and learning now.

For a discussion on negative emissions, one should first become aware of the assumptions underlying them. If we silently accept the understanding of negative emissions as market-driven megaprojects, we run the risk of contributing to the widespread TINA (There is no Alternative) narrative and making other futures invisible.

On the other hand, negative emissions should not be propagated as a one-dimensional solution to the climate crisis. Nevertheless, given the escalating climate crisis, negative emissions can mitigate climate impacts to a limited extent. Therefore, they should not be condemned categorically but should be examined for their emancipatory potential. When the negative emissions narrative is invoked, it seems important to combine criticism of power relations with concrete utopias.

Originally published in German in Analyse & Kritik, February 20, 2024, ak 701