By Caitlyn Sears

The circle of poison describes regulatory failures to reduce the human and environmental harms caused by the global agrochemical industry. Originally used to denote relations between global North (high-income) and global South (low- and middle-income) countries, there is growing evidence that suggests circles of poison are (re)created in South-South contexts.

Little is known about how circles of poison operate in a South-South context, especially in relation to the recent geographic shifts in agrochemical production from locations in the US, UK, and Germany to places like India, China and other global South nations. The origin of the circle of poison can be traced back in the 1980’s; Weir and Shapiro used the term to describe a cycle in which pesticides banned in high-income nations are still produced and exported to low- and middle-income nations. In turn, these pesticides are used predominantly for export crops and returned to industrialized nations in the form of pesticide residues (Galt, 2008). Specifically, the circle of poison referred to the effects of US and European bans on organochlorines in developing nations. This cycle represents theories of dependency in which technologies that are no longer of use in high-income countries get passed on to the developing world (Wright, 1986).

Many scholars have challenged the circle of poison. Recently, Ryan Galt (2008) shows that not only are lower-income countries recipients of harmful pesticides, but they also are likely involved in the promotion and production of pesticides domestically. This is often done through parastatal companies and subsidiaries of multinational firms as part of import-substitution strategies. A more nuanced version of the circle of poison then, is termed the global pesticide complex.

Using quantitative and qualitative data from an ongoing study on agrochemical production networks, I offer here a critical and illuminating case to contribute to current understandings on circles of poison. Following two years of study on the global agrochemical industry and 4 months conducting interviews, my early findings suggest that Malaysia, a middle-income Southeast Asian nation, plays an important role in regional agrochemical production; and is contributing to circles of poison in the region.

Malaysia’s Agrochemical Industry

What might come as a surprise, Malaysia is a top ten global export of herbicides by volume, joining countries such as the US, Germany, Belgium, China and India, according to United Nations trade data. The Southeast Asian nation, the only one among top ten herbicide exporters, has a long history with agrochemicals. Malaysia is the first site where synthetic pesticides were used during an anti-colonial insurgency against the British in the late 1940’s and a crucial site for glyphosate testing in the 1960’s (Hough, 1998).

The agrochemical industry developed alongside the booming oil palm industry, beginning in the 1960’s. In an effort to ease dependence on rubber and tin, the Malaysian government began a diversification program to grow the oil palm industry while addressing issues of poverty among farmers. The Federal Land Development Authority (FELDA) was established for this purpose. FELDA granted plots of land to smallholders for the purpose of growing oil palm and occasionally rubber. This scheme allowed Malaysia to rise to the top producer and exporter of oil palm in the world, surpassing Nigeria.

In order to maintain the oil palm sector and prevent pests and diseases, alongside land development schemes, Malaysia saw the introduction of investment for related, secondary industries, including agrochemicals. Oil palm in Malaysia is known as a hardy plant, but requires significant fertilizer input and can suffer from basal stem rot requiring the use of fungicides. In addition, glyphosate is used heavily for weeding purposes in oil palm plantations.

As early as the 1960’s, capital investment from nations such as the US set up manufacturing plants in Malaysia to begin the production of agrochemicals. Then in the 1980’s, the Malaysian government adopted its National Agriculture Policies (NAPs) in order to further the development of various agriculture sectors (commodity and food crop) and invest in the creation of national chemical industries in support of agriculture. Under these guidelines and unification efforts, the agrochemical and fertilizer industries in the country grew. Malaysia is now home to over 150 agrochemical companies, mostly specialized in formulation, repackaging and distribution and over 3,000 registered products in the domestic market.

Additionally, Malaysia was the first nation in the Southeast Asian region to adopt FAO guidelines on pesticide regulation to create their national legislation, the Pesticide Act of 1974. Having been the first to enact guidelines, this suggests that the country plays a leading and influential role in the region for shaping pesticide regulation, and upholding standards from global organizations. The country has recently adopted more stringent toxicology data requirements for product registration, and recently banned chlorpyrifos, an organophosphate insecticide, just prior to its inclusion in the Stockholm Convention in 2022. The country has banned several pesticides in accordance with both Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions, with a total of 47 bans and restrictions. The conventions’ goal is to decrease the trade of toxic substances through prior informed consent (PIC) procedures and information exchange, as well as through the elimination of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) from production, import, export and use.

A local pesticide retailer in Selangor state, Malaysia. Photograph by Caitlyn Sears.

Malaysia and Circles of Poison

The term ‘circle of poison’ originally described regulatory failures in which banned pesticides were continually produced by high-income nations and exported to low- and middle-income nations. The global pesticide complex offers a deeper, more nuanced understanding of present-day circles of poison, as well as networks of agrochemical production and use. By utilizing the global pesticide complex, we can begin to understand circles of poison as they operate in South-South contexts.

Galt (2008), through his research in the Costa Rican context, finds that low- and middle-income countries are not only recipients of toxicants but often producers and promoters themselves. This view can help us understand Malaysia’s role in recreating circles of poison. As producers, Malaysia’s economy relies heavily on oil palm exports. Therefore, inputs to the oil palm sector are crucial to its functioning, and are secured and guaranteed through greater control over the entire supply chain. A mix of private and state-owned firms produce agrochemicals and fertilizers most notably for majority state-owned oil palm plantations such as Genting Plantations and Sime Darby.

Additionally, the sole synthesizer of active ingredients in the Southeast Asian region is located in Malaysia. Agrochemical synthesis is an upstream process in which chemical molecules are produced to be combined with inert ingredients. Ancom Crop Care has a diversified but niche portfolio; the company’s largest selling product is an outdated arsenic-based herbicide called MSMA (only produced by two companies worldwide, one in Malaysia and one in Israel). Diuron, a pre- and post-emergent herbicide also makes up a large portion of the company’s portfolio. While both of these active ingredients are banned in only 31 countries worldwide, MSMA especially is proven to be highly toxic and rarely used for weed control. In Malaysia, it is widely used in oil palm plantations due to its effectiveness. These active ingredients are exported to neighboring countries, albeit without bans, but strong recommendations against their usage. Indonesia, the world’s largest producer and exporter of oil palm, banned MSMA, but continues to illegally obtain it for use in plantations, many of which are Malaysian owned.

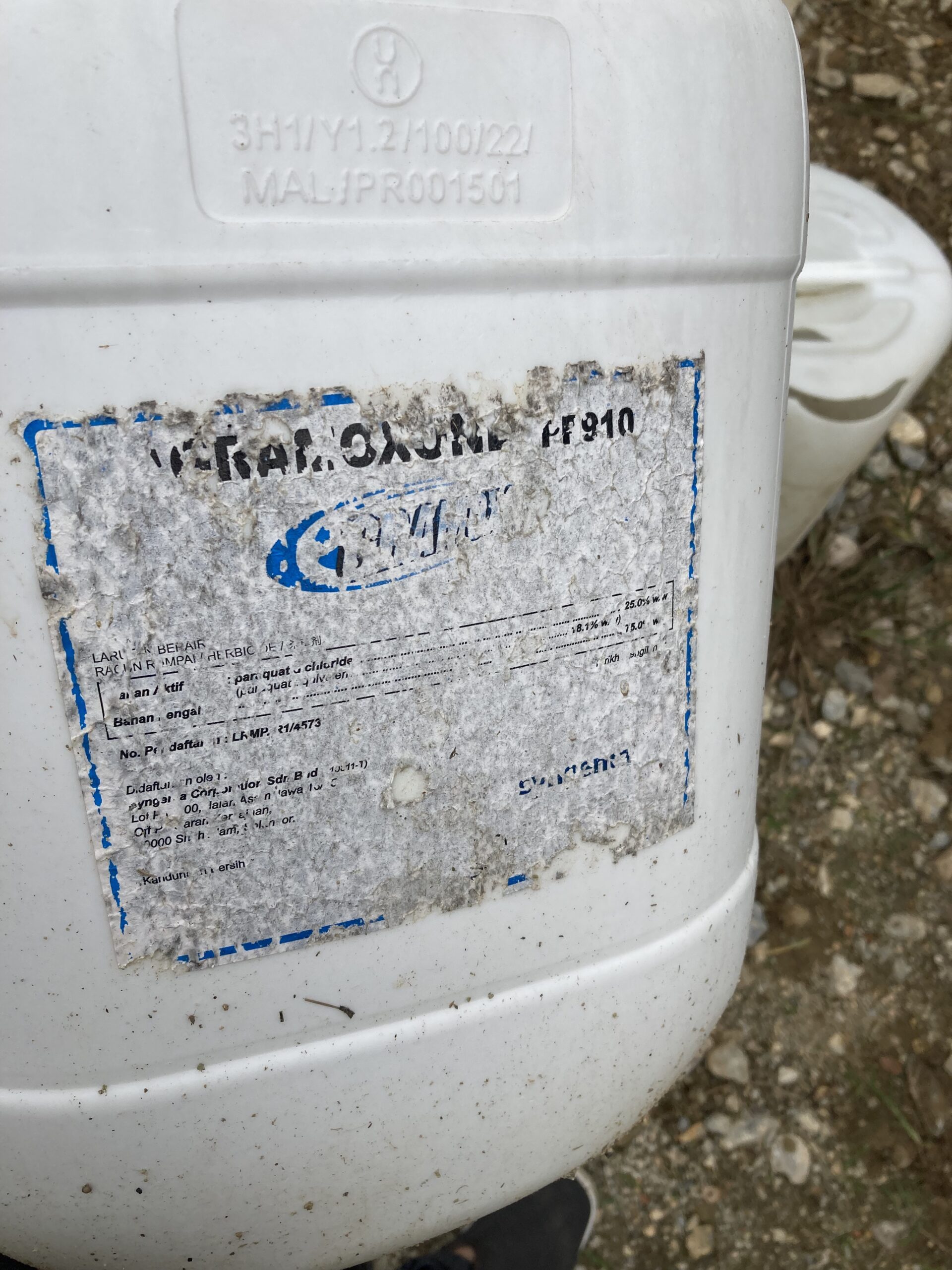

In terms of regulation, Malaysia appears to be ahead of many of its regional neighbors, such as Myanmar, Laos, and the Philippines. The Malaysian government is currently working to amend the national pesticide legislation. In addition to mandatory manufacturing licenses through the Malaysian Investment Development Authority (MIDA) which are required for all industries, new rules would require agrochemical industries to apply for an additional license through the Department of Agriculture. While this could lead to more control over the agrochemical industry, the amendments will continue to exclude controls and tracking on exports. On top of this, porous borders and online shops continue to provide banned pesticides in Malaysia, including a non-selective herbicide, paraquat. Farmers and agronomists continue to search for a worthy substitute for paraquat, which was heavily utilized and promoted despite contestation due to human health concerns beginning in 1985. It was finally banned in 2020. To this extent, firms may still produce products with banned active ingredients, only to export them to countries that have not implemented the same ban (e.g. Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar).

An empty bottle of Gramoxone, the trade name for paraquat, an active ingredient banned in Malaysia since 2020. Photograph by Caitlyn Sears.

Importance of Middle-Income Nations

My initial findings highlight Malaysia as an important agrochemical producer, a node in the global production network, and a player in circles of poison in the global South. While social science research focuses mainly on China, a large global South middle-income agrochemical producer, the inclusion and study of Malaysia complements and expands understandings of industry shifts and circles of poison.

Interestingly, Malaysia offers insight into how circles of poison are re-oriented and operate in the South-South context. The Malaysian case also shows how these interactions and relations may differ, but are not completely divorced from Weir and Shapiro’s original observation in the 1980s. For example, state-owned firms produce and supply agrochemical inputs for the oil palm sector; the country is not a mere unfortunate recipient of harmful toxicants from global North nations. In addition, many of the active ingredient synthesized within Malaysian borders and banned in neighboring countries, easily cross borders. Alternatively, banned pesticides in Malaysia make their way in through various channels, only to be formulated, repackaged, and sent elsewhere. In either situation, circles of poison are thus (re)created among Southeast Asian nations.

In sum, as middle-income nations like Malaysia become sites of agrochemical production and formulation, it is important to expand the remit of critical social science disciplines to include them in our analysis. Additionally, as a top producer and exporter of a crop on which pesticides are heavily used such as oil palm, Malaysia is a critical place of analysis. Palm oil is an ingredient in many food products globally, and new applications are being developed for products such as horse and goat feed, among others. Therefore, the large and growing global demand for products containing palm oil will continue to shape the use of agricultural inputs including both legal and illegal pesticides.

——–

Caitlyn Sears is a PhD candidate in Geography at the University at Buffalo. Her current research is focused on the political economy of agrochemical production networks in Southeast Asia and uneven development.

Bibliography

Galt, R. E. (2008). Beyond the circle of poison: significant shifts in the global pesticide complex, 1976–2008. Global Environmental Change, 18(4), 786-799.

Hough, P. (1998). The Global Politics of Pesticides. Routledge, London.

Weir, D., & Shapiro, M. (1981). Circle of poison. San Francisco. Institute for Food and Development Policy.

Wright, A. (1986). Rethinking the circle of poison: The politics of pesticide poisoning among Mexican farm workers. Latin American Perspectives, 13(4), 26-59.