Residents of La Barceloneta (Barcelona) integrate historical research in their struggle to reclaim the building of a 100-year-old consumer cooperative back for public use. How can history inspire social transformation?

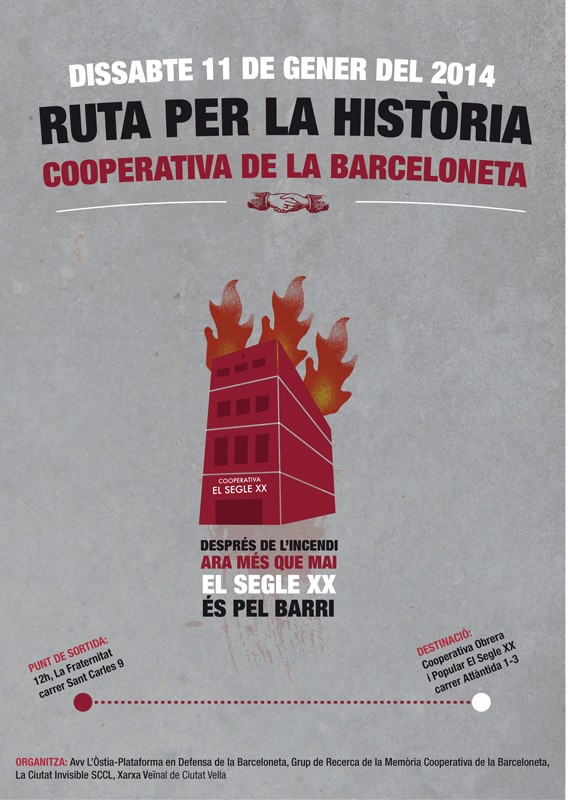

Poster “El Segle XX és pel barri” (“The Twentieth Century is for the neighbourhood”). Source: Grup de Recerca de la Memòria Cooperativa de la Barceloneta.

When Aymara people in South-America look ahead they are facing the past. Literally. Researchers who investigated Aymara language and gestures have established that, unlike all the studied cultures and languages of the world, they refer to the past by gesturing ahead, while the future is situated in the back of the self. The example of the Aymara indigenous people, when reflecting on how history can be useful for activists participating in socio-environmental conflicts, challenges our preconditioned views. We can put history into the foreground, not just as the background or the context of present events but as a central resource for the present and the future.

“All history is contemporary history” – famously asserted Benedetto Croce.

But it is not only that we all write and research within the context of our time. It is also that the stories and narrations that we unveil impact on today. They can affect how we look at the past – but especially, when it involves social movements, they can also shape how we look at the present and at the future, at what is conceived as possible and impossible today and tomorrow.

As the Zapatistas claim, it is necessary to “open a crack” in history. On January 1st 1994, the very same day that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into force, the Zapatistas launched their revolt in the mountains of Southeast Mexico. From their very First Declaration, they emphasised they were the result of 500 years of resistance to colonialism.

One of the expressions of such resistance is precisely their critique to how history has been written. A history that tells the story of the elites just makes the present state of things seem natural, leaves aside the subalterns and silences their past. Against this type of history appropriation, Zapatistas claim the need to “open a crack”– to write the history of the exploited. A crack that disrupts also the idea of unidirectional, non-linear history, opening a loophole that challenges views of what is in front of us and what in our backs. A crack that permits us to look to the past ahead – like the Aymara – as memories of the alternative non-disposable future. Once the past is reclaimed, the door to reclaim the future swings open.

Reclaiming silenced pasts is a task to be done both in the archives and the streets, both in libraries and mountains, listening to stories and reading dusty records. It can be about how a revolution was silenced and obliterated from history, as shown in the work of Michel-Rolph Trouillot on the late 18th century in Haiti. And also about how dictatorships try to wipe out the memory and heritage of those who opposed them. When, like in Spain, elites have succeeded to remain in power for decades, the stories of disappeared workers and activists and their emancipatory projects frustrated by a 40-year long dictatorship risk being left aside and silenced forever.

The Case of Segle XX building in Barceloneta

In December 2013, residents of La Barceloneta (Barcelona, Spain) announced a demonstration to reclaim the empty building of the El Segle XX (“The Twentieth Century”) cooperative for its public use. El Segle XX had been founded in 1901, but after years of decadence during the Francoist dictatorship, the cooperative was dissolved in the late 1980s and the building later abandoned.

At least since 2008, the La Òstia neighbourhood association began collecting information about the history of the neighbourhood and interviewing veteran residents. The importance of several cooperatives – El Segle XX among them – as spaces of socialization, consumption and cultural centres since the late Nineteenth century soon emerged as a central aspect of the residents’ memories. Later, the Barceloneta Cooperative Memory Research Group (Grup de Recerca de la Memòria Cooperativa de la Barceloneta) continued the work of the association focusing on the history of cooperatives by diving into archives, recording interviews, organising guided tours and other activities.

In Barceloneta, historically a working-class neighbourhood with low salaries and few public and social facilities, but now under high touristic pressure, the use of the El Segle XX building became a symbolic claim to the municipality. The historical connotations of the building and of the cooperatives’ movement were manifest. Since the last decades of the Nineteenth century, the importance of the organisation of cooperatives in Barcelona grew and was part of a wider international movement. In Catalonia, cooperatives had their heyday during the democratic period of the Second Republic (1931-1939), when thousands of families became members. Very often, they had their own theatres, bars and shops. Through consumption cooperatives, they allowed avoiding intermediaries between consumers and producers and thus also represented a nexus of the urban space to the surrounding agricultural environment, which fed it.

However, following a military coup that unleashed the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and with the victory of Franco over the Republicans, cooperatives never regained the activity hey had had before. In fact, during the conflict, Barcelona was on the Republican side and Barceloneta was bombed so heavily that it had to be evacuated. El Segle XX was hit by Fascist bombings and reduced to ashes. Although the building was rebuilt after the war, during the dictatorship its activity languished, and most cooperatives were dissolved and their buildings sold. The El Segle XX building passed to private hands at some point during the early 1990s, following an irregular process of dissolution of the cooperative.

In recent years, although the land on which the building is built was categorised by the City Council as a public facility, rumours of private commercial projects for the building circulated, along with the growing pressure of gentrification and tourism in the maritime neighbourhood of Barceloneta. This spread uneasiness among the residents. In the final days of 2013, two weeks before a scheduled demonstration, an apparently fortuitous fire damaged part of the building. This event fostered a united front of the associations and residents of the quarter, and just a few weeks later, more than 30 organisations signed a statement asking the District to either expropriate or buy the Segle XX building. They also demanded a transparent investigation about the fire and the legal state of the building property, as well as the commitment of the City Council to keep the building categorized as a public facility.

At the end of the demonstration, in front of the El Segle XX building, several residents intervened emphasising the historical role of the cooperative in Barceloneta. The march ended with two posters plastered on the wall of the building. One vindicated the historical memory of cooperativism with a quote from 1899; the other was a blank poster to be filled by participants with their ideas for the future uses of the space, under the title “What do we want for El Segle XX?” (“Què volem per al Segle XX?”). In the same fashion, the website of the Barceloneta Cooperative Memory Research Group, whose members had an active role in the march, stated clearly their views on the uses of the memory of cooperativism:

“More than an exercise of historical memory, it comes to us as a memory of the future: the practices of cooperation give us a powerful tool to face a present of cutbacks in social services and to build a shared future”.

Residents of Barceloneta in front of the El Segle XX building at the end of a demonstration. Source: El Periódico.

Unearthing stories of the past, reconnecting struggles for the future

In a rapidly changing barri (neighbourhood), with growing pressure from luxury tourism stimulating higher rents and pushing former residents out, associations have resorted to historical research to enhance their struggles. Recording memories, collecting scans of old pictures and newspapers, finding old records or mapping places that have disappeared, residents have found a way to narrate their own story.

As highlighted by activist researcher Emma Alari, participatory mapping has been an essential tool in the neighbourhood struggle. On one hand, maps were used by Barceloneta’s residents to display the different threats suffered by the neighbourhood. In this regard, the collaboration with mapping activists Iconoclasistas constitutes a good example of the use of collaborative mapping for social movements. But mapping can also be a historical project. By mapping both long and recently disappeared places in “Geografia Esborrada de la Barceloneta” (“Barceloneta’s Deleted Geography”), residents not only narrate their history but configure an emotional geography of the barri, which binds together the stories of squatted houses already demolished with the story of buildings like El Segle XX or the Escola del Mar, a wood-constructed school on the seaside, which was burnt by Fascist bombings during the Spanish Civil War.

Such stories are disseminated by walking and talking together with residents (on organised guided tours), but also leaving the option of doing it alone listening to the audio contents available on the web. Through the map, these stories weave new connections between the past, the present and the imagined futures. Guided tours provide chances for the interaction between those researching the history of the neighbourhood and their inhabitants, confronting and enriching each other’s stories. Altogether, this strengthens the claim of spaces such as El Segle XX for common uses in the neighbourhood, by reconnecting the stories of the residents’ relation to this space with the historical research about its function for the social movements of the past.

After years of actions and campaigns in the neighbourhood, the Barcelona City Council has finally committed to starting the process of expropriation of the El Segle XX building to give it back to the barri. The struggle, however, is far from over. As the recuperation of the building is close to becoming a reality, the neighbourhood platform designs its own project for the uses of the building through a grassroots process. In a major open meeting in the square, residents wrote their ideas for the future uses of the cooperative building on several large-size copies of the 1939 project drawings to rebuild the cooperative after the war, which they had located in the archives.

Not only was this a practical way to collect all the ideas for the different floors of the building and a reminder of the building’s past. It was also an inadvertently symbolic gesture: the maps of the project to rebuild El Segle XX after the Fascist bombings and the occupation of Barcelona in 1939 were recycled 76 years later to discuss an alternative future with the barri’s residents. The past can be a resource for imagining alternative futures – in a very material way.

Planning the future of the El Segle XX cooperative on the base of the 1939 maps located in the municipal archive. Photo by Santiago Gorostiza.

While some would see a gloomy and nostalgic flavour in this struggle, activists explicitly state that they don’t intend to idealise, nor to romanticise, a return to a static lost past. They want to learn lessons about past experiences tried and failed, understand past hopes for imagined futures, explore the daily life and the problems of the neighbourhood in the past and its connections to today. Following Walter Benjamin, in this way nostalgia can be an emotion connected to transformation and even revolution. Past experiences are opportunities for reinvention, possibilities for alliances across time. Stories like the one told by the El Segle XX building can be, as Italian authors Wu Ming and Vitaliano Ravagli have asserted, “axes of war to be unearthed”.

Further Reading

Alari, E., 2015. «El barrio no se vende» Los mapeos de la Barceloneta como herramienta de resistencia vecinal frente al extractivismo urbano. Ecología Política, 48, 36-41.

Armiero, M., 2011. A Rugged Nation. Mountains and the Making of Modern Italy. The White Horse Press, Cambridge.

Barca, S., 2014. “Telling the Right Story: Environmental Violence and Liberation Narra-tives”. Environment and History. 20, 535-546.

Lowy, M., 2005. Fire Alarm: Reading Walter Benjamin’s ‘On the Concept of History’. Verso, New York.

Ming, W., Ravagli, V., 2005, Asce di guerra. Giulio Einaudi Editore.

Ponce de León, J. (ed.), 2001. Our word is our weapon. Selected writings of subcomandante Marcos. Seven Stories Press, New York.

Pulido L., Barraclough, L., Cheng, W. 2012. A People’s Guide to Los Angeles. University of California Press.

Risler, J., Ares, P., 2013. Manual de mapeo colectivo: recursos cartográficos críticos para procesos territoriales de creación colaborativa. Tinta Limón, Buenos Aires.

Trouillot, M-R., 1995. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Beacon Press, Boston.

*This post is part of a series sharing chapters from the edited volume Political Ecology for Civil Society. Santiago Gorostiza’s contribution is included in the chapter on social movements. We are eager to receive comments from readers and especially from activists and civil actors themselves, on how this work could be improved, both in terms of useful content, richness of examples, format, presentation and overall accessibility.

One Comment