By Eva Camus & Panagiota Kotsila

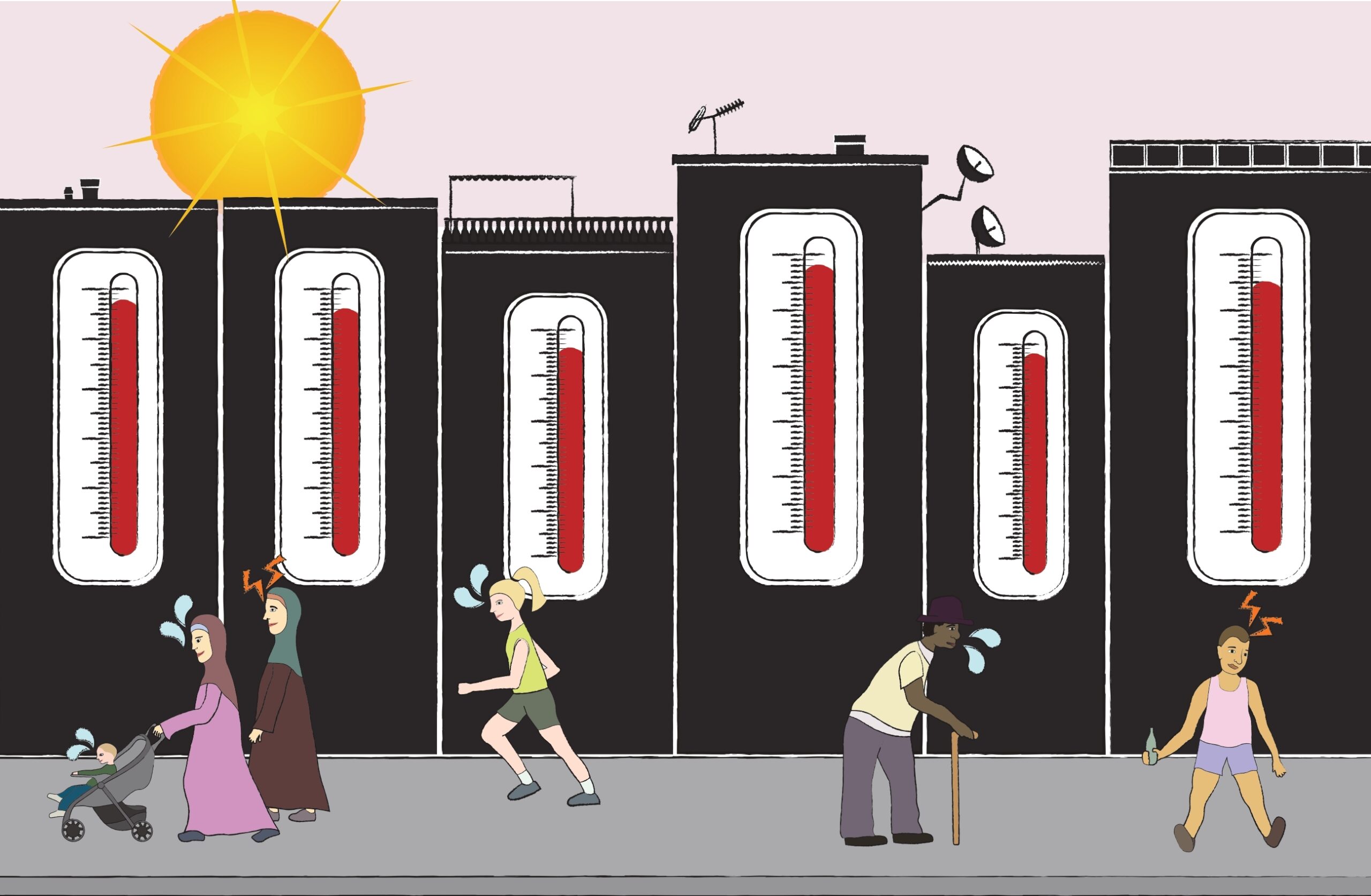

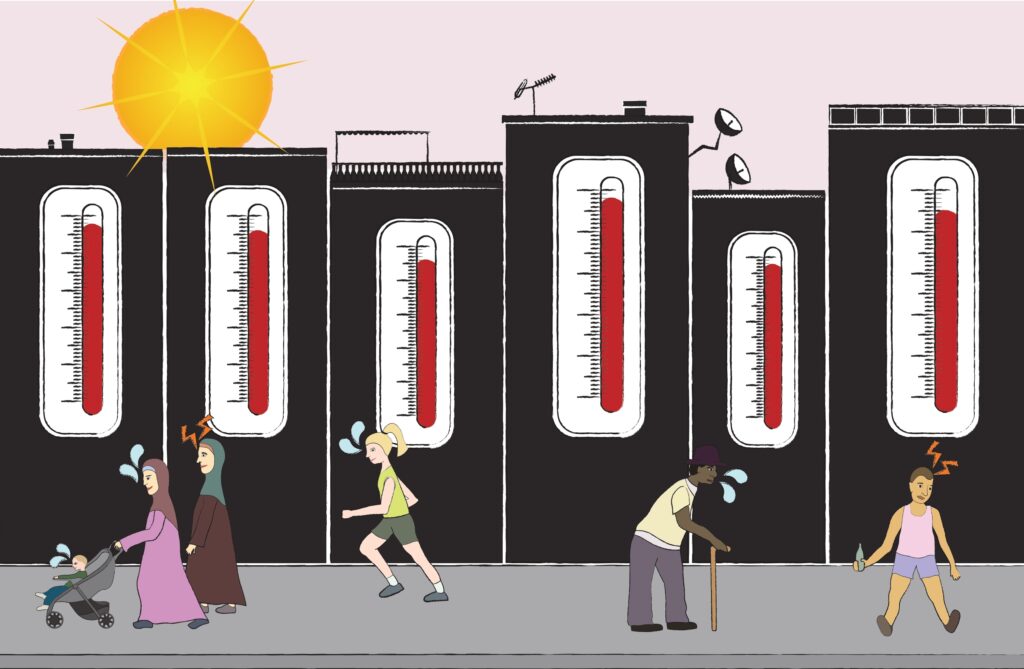

Heatwaves expose deep inequalities, hitting racialized migrants hardest due to race, gender, class, and poor housing. In Neukölln, Berlin, we see the urgent need for inclusive, locally-informed climate adaptation strategies that prioritize migrant voices, housing justice, and equitable access to cooling resources.

The numbers are staggering. Last month, the Climate Risk Index 2025, published by Germanwatch, documented the growing impact of extreme weather events globally. Between 1993 and 2022, more than 765,000 people have lost their lives due to extreme climate events, while over 9,400 climate-related disasters, including hurricanes, floods, storms, and heatwaves, caused economic damages exceeding $4.2 trillion (Climate Risk Index, 2025). But behind these figures lie deeper questions: Who is most at risk when disaster strikes? Who shoulders the weight of climate?

While some stay cool in air-conditioned offices, shaded neighborhoods, or public cooling centers, others, including migrants, low-income workers, and racialized communities, endure the heat in overcrowded apartments, precarious workplaces, and public spaces where they are often unwelcome. Across European cities, adaptation strategies often overlook these inequalities, reinforcing existing patterns of environmental injustice and exclusion.

Who gets to stay cool? Heatwaves and climate injustice in European cities

Heatwaves are not just a weather event; they are a crisis of inequality (Anguelovski et al. 2025). As temperatures rise, cities become heat traps, where dense infrastructure and the urban heat island effect push temperatures higher than their rural counterparts and disallow urban neighborhoods from cooling down during the night. In Europe, risks are growing as it has become the fastest warming continent (Climate Risk Index, 2025). While Mediterranean cities have long coped with high temperatures, northern European cities are now also struggling. Many buildings, designed to retain warmth, make cooling difficult, and where air conditioning is scarce both in private homes and public buildings, heat stress is an increasing concern.

Not everyone experiences extreme heat the same way. As political ecologies of risk have long noted (see Collins 2008;Wescoat 2019; Huber et al.), vulnerability to environmental and climate impacts is socially produced. Power relationships are reflected in how such impacts and the subsequent policies of mitigating or adapting to them are governed, and social structures determine who will be most at risk and whose voice will be heard in processes of risk assessment, prevention and policy. The risks that climate change poses to human health and well-being are no exception.

Extreme and prolonged heat impacts places and communities by building on and magnifying existing inequalities related to urban planning and zoning decisions, historical patterns of socio-spatial exclusion and segregation, as well as to everyday patterns of life and work, hitting those at the most precarious positions the hardest. Research has identified children, older adults, and those with pre-existing conditions as particularly at risk, taking into account the biological predisposition of different people to the effects of heat (Rebetez et al., 2009; Kovats and Hajat, 2008). However, we need to take a closer look at the role of deeper and historical social, economic and cultural determinants of such vulnerability, including how race, gender, class, and living conditions are just as decisive of factors when defining vulnerability as biological predisposition (Abi Deivanayagam et al., 2023; Anguelovski & Kotsila, 2023; Anguelovski et al. 2025).

In the context of urban life in cities in Europe, some of the most socially vulnerable groups are racialized migrants; people that come from countries of a majority world context and now live in Europe. Despite increased attention to how racialization and marginalization shapes heat injustice, we have seen limited attention on the topic from scholars in Europe. In response to this gap in our understanding of climate injustice in EU cities, we designed a pilot research project to examine how migrants experience, understand and react to extreme and prolonged heat in the context of Neukölln neighborhood in Berlin, Germany.

Created by: Jana Dabelstein

@mentalnotearchive (Instagram)

http://www.linkedin.com/in/janadabelstein

During May and June 2024, we held 2 participatory workshops with 11 majority-world migrant residents. We adapted the Relief Maps method, to capture intersectional dynamics of heat-related dis/comfort in everyday spaces, and the contradictions often faced by migrants regarding thermal versus emotional comfort.

Firstly, we found out that ten out of eleven participants find public transport uncomfortable in relation to heat, mainly due to poor ventilation, high temperatures, and overcrowding. Gender significantly influences these experiences, with public transport showing the highest average discomfort in the gender dimension. Five of eight women and gender-nonconforming individuals reported insecurity due to harassment, with a young woman from Mexico, describing “a lot of sexual and sexist harassment.” The results also reveal that race and ethnicity contribute to discomfort on public transport, with four participants experiencing stereotyping, judgment, and overt racism.

Agreeing with scholars who have identified migrants working in construction, agriculture and manufacturing as particularly vulnerable due to their exposure to long hours in direct sunlight, or poorly ventilated environments with minimal protections against extreme temperatures (Hansen et al., 2014; Venugopal et al., 2014; Messeri et al., 2019), we found that beyond physical conditions, deeper socio-cultural structures and circumstances—such as language barriers—also significantly influence their access to thermal comfort. Five participants in our study noted that limited German proficiency restricted their job options, made it difficult to communicate with employers, and left them unable to advocate for better conditions. The exclusion from workplace decision-making processes mirrors broader patterns of labor control in migrant economies, where language is often a barrier to social mobility and labor rights advocacy (Collins, 2012).

We also found that for migrant women, these vulnerabilities were even more pronounced. Many are overrepresented in caregiving, cleaning, and service jobs, where gendered expectations of emotional and physical labor heighten their exposure to heat. One participant, a childcare worker, described how the burden of protecting others during heatwaves made her own discomfort secondary:

“If I have to go to work on a hot day, then it’s kind of annoying because I work with kids, and we have to go to the park. Then it’s like I’m stressed about the bodies of 20 kids instead of mine. I’m stressed about whether they have sunscreen, if they have their hats, if they’re drinking water, if they’re not burning themselves on the metallic parts of the park. And then I’m super exhausted. […]”

Her experience reflects a broader reality of gendered workplace precarity, where migrant women are expected to manage heat exposure not only for themselves but for those under their care, often while earning low wages and receiving little institutional support (see also Sultana, 2014; Truelove & Ruszczyk, 2022).

Furthermore, housing conditions turned out to be a key determinant of climate vulnerability. Yet, for many migrants, their home offers very little protection from extreme heat. Scholars in urban political ecology emphasize that thermal comfort is not just about the level of air temperature, but also about access to safe, affordable and stable housing which is in turn deeply shaped by economic and social inequalities (Anguelovski et al. 2025; Checker, 2020).

Our workshops, indeed, revealed that while some participants found relief in good ventilation or cooling infrastructure, others faced overcrowding, poor airflow, and noise pollution at home, making heat waves unbearable. One participant, living with five others, described her home as “impossible to endure” without air conditioning, underscoring how housing conditions shape thermal comfort as much as outdoor temperatures. This is compounded by the constant struggle connected to securing an affordable home, let alone one that offers relief during times of heat. Many participants described constantly moving in search of affordable rent, reinforcing the argument that housing precarity compounds climate risk (Rolnik, 2019). With rising rents and few housing options, cooling often became a secondary concern, demonstrating how heat vulnerability is inseparable from economic instability and displacement. As one participant shared:

“I’m paying a lot for a small studio, and this is the fourth time I’ve moved in a year. Most housing is overpriced for the little space it offers.”

Exclusionary adaptation: who gets to benefit from green cities?

At a systemic level, migrants’ ability to adapt to extreme heat is shaped not just by economic hardship but by policies that reinforce exclusion. Neoliberal climate strategies, rooted in historical racism and capitalist exploitation, limit access to resources, making it harder for migrant communities to cope with rising temperatures (Kotsila et al., 2023). While European cities promote sustainability and climate adaptation, these efforts often mask, and indeed exacerbate, deep-rooted inequalities. Green infrastructure projects (including parks, permeable surfaces, green roofs, regeneration of waterfronts, etc.) are celebrated as solutions to urban heat. However, these are seen to frequently drive-up property values, displacing low-income and migrant residents and making public spaces less accessible (Anguelovski et al., 2018).

Parks and cooling green corridors offer relief from extreme heat, yet for many migrants, these spaces remain unwelcoming due to harassment, discrimination, and police surveillance, as participants in our study described. Eight participants said they seek heat comfort in parks, and green spaces were also valued for their financial accessibility, particularly by those unable to afford private cooling options. Despite their cooling benefits however, experiences of exclusion and racial profiling severely also shape access to these environments. Three women and non-binary participants reported feeling unsafe in parks due to histories of sexual harassment and cultural judgment.

Access to life-saving information is another barrier. Many migrants struggle to access heat warnings, emergency resources, and public health information due to language barriers and weak institutional support (Kotsila et al., 2023; Lebano et al., 2020). Even when cooling centers exist, social exclusion and lack of networks prevent many from using them. Our findings revealed a significant gap in awareness regarding municipal or NGO-provided heat relief locations. As one participant shared:

“Honestly, I do not know about these spaces. I have not heard about these places and did not know they existed in Berlin or Germany.”

The absence of commentary from other participants suggests that this lack of awareness is widespread. Beyond information gaps, social dynamics also played a role in limiting access. One participant, described feeling “very foreign in this place”, highlighting how migrants may feel unwelcome or out of place in institutional spaces designed for heat relief.

Rethinking climate adaptation: from exclusion to justice

If European cities are to adopt adaptation strategies that benefit all and prioritize the most vulnerable, adaptation must move beyond mainstream technocratic approaches that treat the city as a blank slate and assume “trickle-down” benefits. Local context, the history of neighborhoods and the realities of those who inhabit them, need to be the pillars of climate adaptation, including knowledge and practices from networks and collectives that have long sustained, involved, and provided care for and with the most vulnerable.

Migrants, often framed as passive victims of risks, hold crucial knowledge about surviving adversity and detecting risks of social exclusion and injustice, because they often have long experience of such processes. Heat knowledge, for example, consists of histories of adaptation in hotter climates and resource-scarce environments, but also by years or generations of people living in conditions were heat often becomes a health-threatening factor during or after the migration journey.

Understanding climate health vulnerability through the experiences of migrants requires centering their situated knowledge and everyday adaptation practices. In our efforts to capture this through the workshops in Neukölln, we heard participants’ proposals for more shaded pedestrian and cycling routes, increased public water fountains, and capped-price fruit and drink vendors to ensure equitable access to cooling. They also suggested developing an app to map shaded park pathways, helping residents navigate cooler routes during extreme heat.

Urban adaptation strategies remain shaped by top-down processes and resulting policies that exclude the communities mostly at risk. This is not just a procedural or coincidental oversight. It is the result of the socio-economic production of urban nature, including how ecosystems have been managed, altered and commodified, within and outside of cities for the purpose of urbanization and urban economic growth; of how communities of color and the working class have been assigned certain roles and social positions, reflecting on the formation of certain types of neighborhoods and housing complexes; as well as of how nature is being increasingly instrumentalized to proxy urban health and climate protection in order to promote powerful interests such as those of the tourist or real estate industries.

Instead of climate policies that raise property values and displace vulnerable communities, adaptation must prioritize housing justice, labor protections, and equitable access to cooling infrastructure. Public spaces should be designed with inclusivity and safety in mind, ensuring migrants and racialized communities feel welcomed rather than policed or excluded. Most importantly, cities must create spaces where migrants’ experiences and adaptation strategies are valued as essential. In the face of intensifying heatwaves, relief cannot remain a privilege. Climate adaptation must be about redistributing resources, dismantling systemic inequalities, and ensuring that no one is left to endure the heat alone.