By Nelly Alfandari, Daniel Papillon, Austin Matheney.

How can research and education be useful to social movements struggling for eco-social justice? How do we imagine collaborations between academic research and political organising? What would be critical issues, caveats, and red lines?

As members of the climate justice project Casa dels Futurs, and researchers at ICTA (UAB), we aimed to address these kinds of questions at a workshop in Barcelona last autumn. Drawing from our experiences, we discussed situated research practices and what these would resemble as part of eco-social organising.

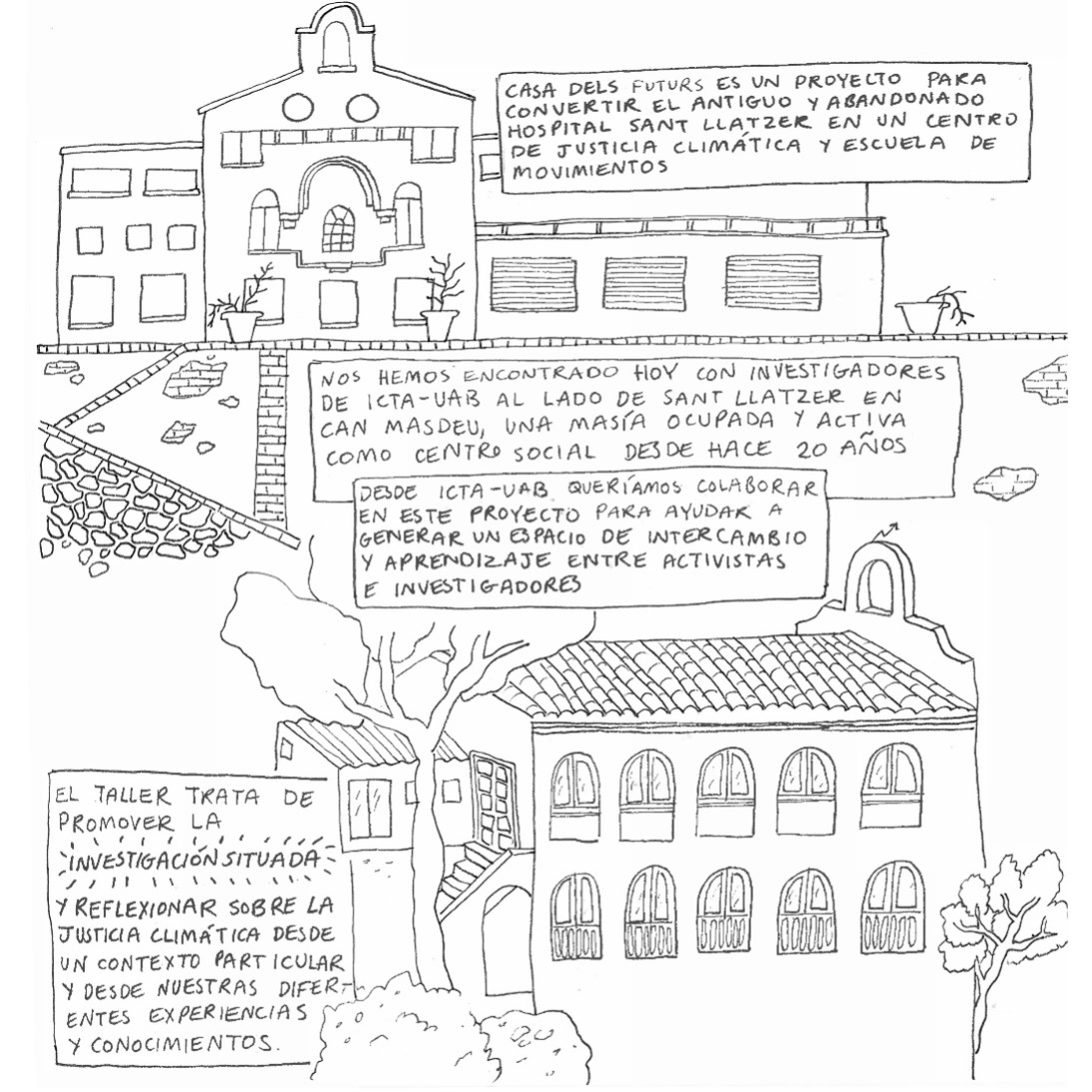

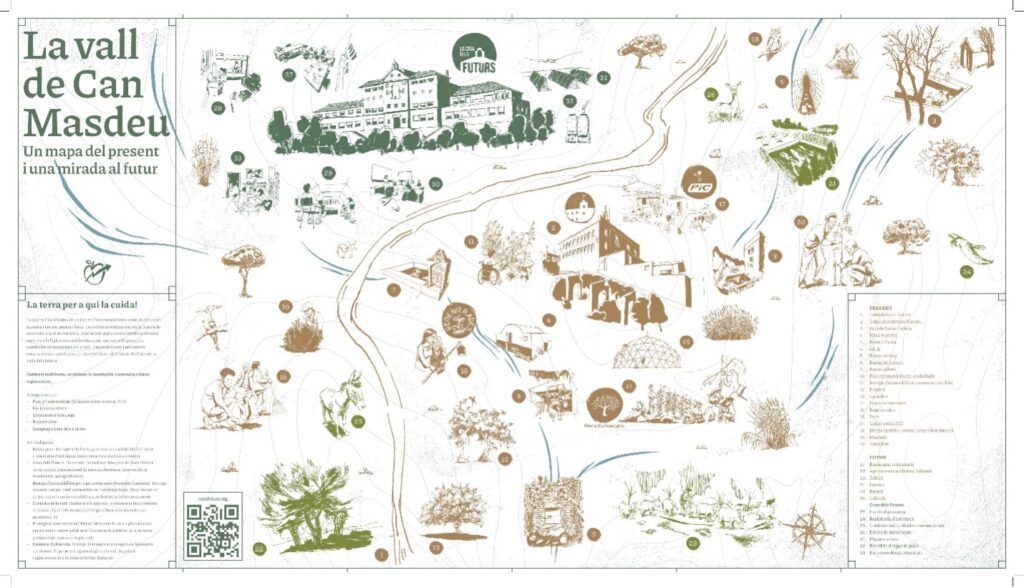

Figure 1: “Casa dels Futurs is a project to convert the old and abandoned Sant Llatzer Hospital into a Climate Justice Centre and Movement School”; “We have met here today with researchers from ICTA-UAB, next to Sant Llatzer, at Can Masdeu, an occupied mansion, functioning as a social centre for the past 20 years”; “As ICTA-UAB we wanted to collaborate in this project to generate a space for exchange and learning between activists and researchers.”; “The workshop today will focus on promoting situated research and reflect about climate justice from this specific context and from our different experiences and knowledges”.

Casa dels Futurs is an international climate justice centre in the making. We, people from different backgrounds and positionalities, some of which authors of this post, are working to create a climate justice centre and a social movements school, inspired by projects such as the US-based Highlander Folk School, in the former Hospital de Sant Llàtzer, an abandoned building with no social use since the mid-1970s, in Barcelona, Spain.

In autumn 2022, members of Casa dels Futurs and researchers at ICTA-UAB organized a workshop trying to address questions relating to how research and education can be useful to social movements struggling for eco-social justice and how we imagine collaborations between academic research and political organising, including caveats and challenges in the process.

Casa dels Futurs is a project organised along three axes: climate resilience (working on local climate change challenges), global solidarity (working internationally with land defenders, focusing on the global South) and knowledge (building a permanent movement school for co-learning towards eco-social justice through place-based popular learning, i.e., education and research).

We believe that a fundamental aspect of climate justice is access to infrastructure: a place to organise from, to support and learn from each other across social justice movements, as well as to provide refuge to those who need it. We are thus working towards liberating a building as a permanent infrastructure of care for planet and people. In the meantime, we are organising in different spaces across the city as to build our practice. One such place is the occupied social centre Can Masdeu in the Collserola mountain, next to the Sant Llatzer hospital.

In our work, we pay special attention to place, meaning the context and location where we organise from. This is a key aspect of our pedagogy. We are inspired by a critical place-based pedagogy (Gruenewald, 2003). Critical place-based pedagogy aims at combining aspects of critical pedagogy and place-based education. This is how Gruenewald justifies it: “Place-based pedagogies are needed so that the education of citizens might have some direct bearing on the well- being of the social and ecological places people actually inhabit. Critical pedagogies are needed to challenge the assumptions, practices, and outcomes taken for granted in dominant culture and in conventional education.” (p.1) By putting more “place” in critical pedagogy, and more “people” in place-based education, “critical pedagogy of place aims to contribute to the production of educational discourses and practices that explicitly examine the place-specific nexus between environment, culture, and education. It is a pedagogy linked to cultural and ecological politics, a pedagogy informed by an ethic of eco-justice … and other socio-ecological traditions that interrogate the intersection between cultures and ecosystems.” (p.10)

From our perspective, this translates into paying special attention to the places we organise in, the knowledges and practices, as well as to the histories and struggles of these places. For if these histories, current affairs, and desired futures are not engaged with or glossed over, (research) processes and outcomes will be inherently unjust.

The mere existence of the Collserola range of mountains and forests is a caring gesture towards Barcelona and all its inhabitants, be it through its activity in absorbing air pollution, cooling the general temperature or regulating potential floods. After a long period of being mostly an agricultural area, the 20th century witnessed a transition to a forest ecosystem that culminated in Collserola being declared a natural park in 2010. Issues such as the use of the poorly defined buffer zones between the park and the city or the breaks in natural continuity are supposed to be dealt with through the contested 2019’s PEPnat (Pla especial de protecció del medi natural i del paisatge del Parc Natural de la Serra de Collserola).

Conflicts and negotiations between various actors are ongoing around various fronts: the high percentage of the park’s surface privately owned, the role of expanding agricultural land especially to consider local food provision, the need to halt extractive, cement and mining operations and ensure ‘proper’ restoration, and the exceedingly high rate of hunting in the mountain.

Even more striking, is the issue of water. The Vallvidrera and the Sant Medir streams in Collserola are threaten by pollution, construction and development. In the Can Masdeu valley, as in Catalunya more widely, a battle with draught and frequent forest fires is ongoing. The Sant Llatzer hospital is not connected to the municipal water system. In our projection of working from this place, water must be at the heart of our organising and structuring the project both physically as well as conceptually. At the same time, by reclaiming an empty building for public use in a city like Barcelona, an engagement with different struggles across the city, such as housing and touristification, where speculation of property and tourism industry leaves locals without land to live a dignified life on, comes to the surface. Located on the Mediterranean, we project the climate justice centre to also function as a refuge and organising place for climate refugees and climate justice activists. In this way, the project aims to intervene in a more global and historical cycle of extractivism and displacement between the global north and the global south. Recently for example, we have been on a listening tour, engaging with and exchanging experiences of struggles and hopes around possible transformations around the body in relation to land, in a project we call “Cos i Territori” (body and land) in collaboration with Taula per Mexic and Mujeres Pa’lante. By practicing a listening with and through the body in relation to the land, we are practicing a critical place-based pedagogy.

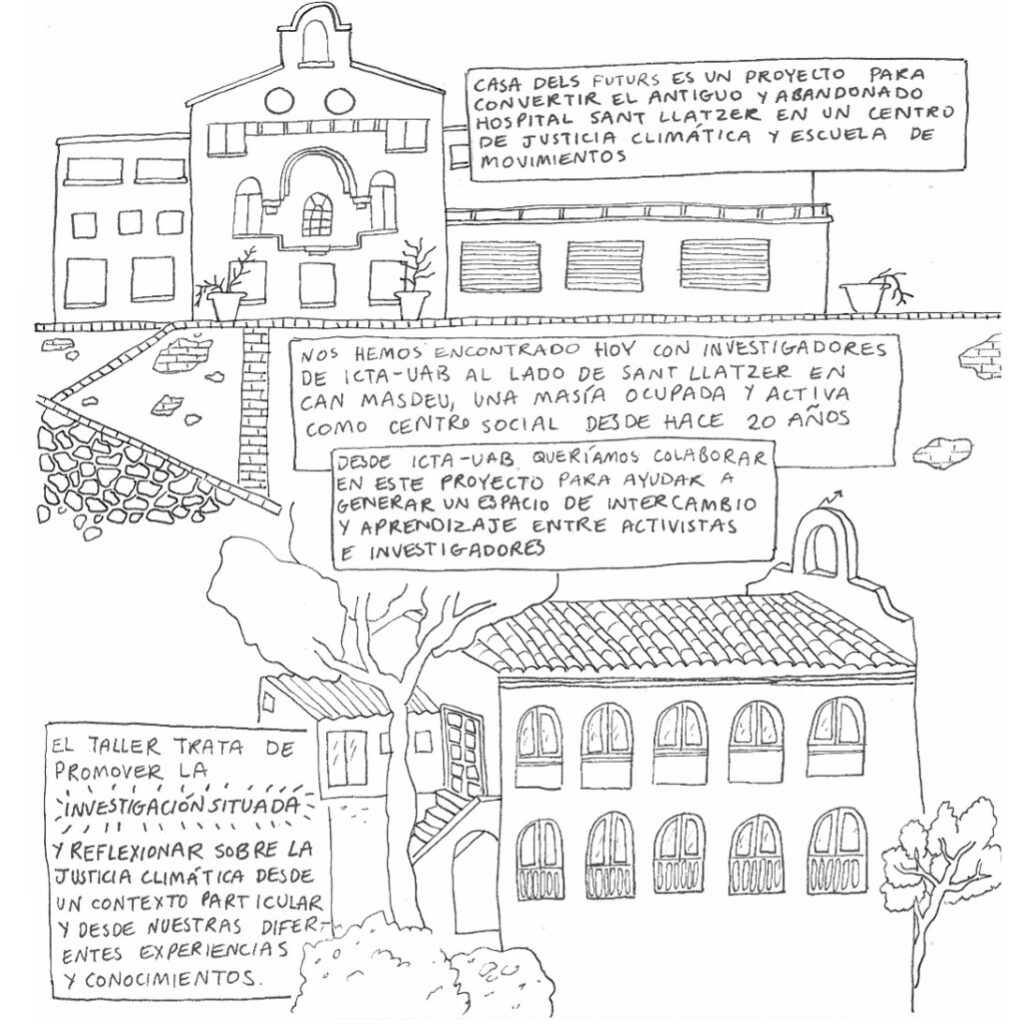

Figure 2: What practical advice can we give to ensure that climate justice-based research comes to action? “I am not saying that I am an example, but I think that as researchers we need to take part in direct action.. and leave our comfort zone! The time is now!” “From within Academia we need to support projects and implicate ourselves in social movements!”

In our full day workshop in Can Masdeu, we discussed situated research as generating knowledge from a place, a context, and a history—from social relations. It means there are other ways of understanding the world—that there exist other ways of knowing outside of a western framework. From there, we deemed necessary to touch on the local challenges to the Collserola mountain, such as lack of water, fire risk, land privatization, and a lack of transparency of the management of the area. Our reflections on situated research included sharing good and bad practices to figure out how situated research could be useful in the context of Casa dels Futurs.

For example, we discussed the importance of situating the researcher, and the research questions in the field. How do they relate to local people and local struggles? Can the research be useful? Can research relationships be institutionally or structurally useful for the local context? What local knowledges does the research engage with, or fail to engage? What is the objective of the research and what happens with the results? Who are they for? Is it the right moment of the struggle for research? Perhaps something else could be more useful?

We also reflected on the importance of longer term research relations with movements, but which are often limited by the time span of a research project, in turn often promoting fast research in the spirit of producing more rather than better or more meaningful outputs At the same time, we discussed the different layers of precarity amongst everyone involved, including institutionally for researchers within their universities, as well as cost of living related precarity for many people involved in different struggles. We thought about how to situate the research usefully within these panoramas as well.

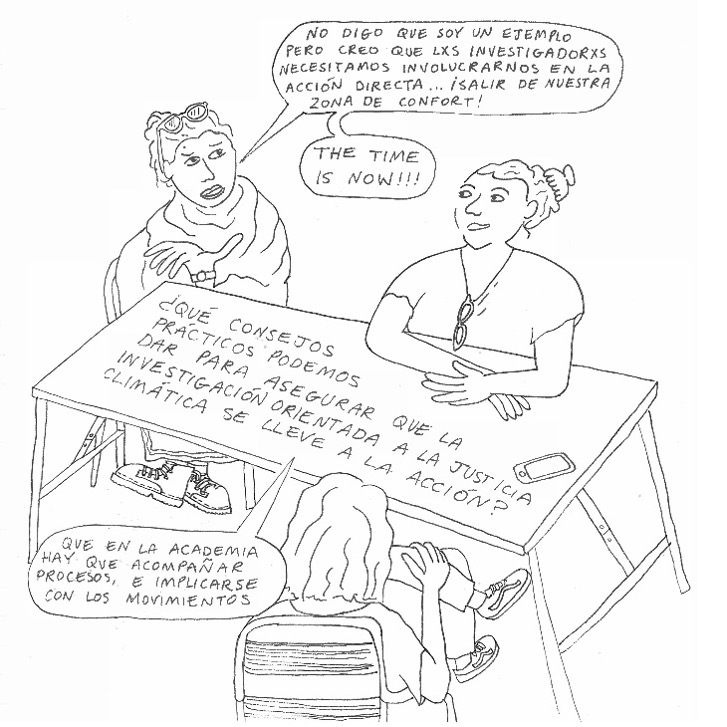

Our mapping workshop with the allotments of the Can Masdeu valley, was part of a longer process of setting up a situated research practice as part of Casa dels Futurs. An earlier example was a counter mapping activity that we organised with members of the collective allotments located in the Can Masdeu valley (los huertos comunitarios). Together, we drew maps of the past, present, and desired futures of the valley, locating and telling stories about animals, plants, materials, practices, and know-hows.

Figure 3: Mapping project of the Asamblea of the Can Masdeu (which includes the occupied social centre, the community garden and the Casa dels Futurs project, and other local groups) valley, showing existing aspects of the valley (brown), an imagined future (olive green), and the projected climate justice centre (dark green). It also pictures the manifesto of the assamblea Can Masdeu valley. For a closer look, check out https://canmasdeu.net/manifesto/

We are now at the stage of thinking practically and methodologically about how to continue our collaboration with academic researchers. Often researchers are passing by and are disconnected from the places activists work in, and oftentimes do not speak local languages. At the same time, they have dedicated time and a structure to support their research, as well as methodological and subject specific knowledge. Sometimes, some of us are researchers, too.

During the workshop with ICTA, a local teacher expressed that a collaboration with a researcher from ICTA would be immensely useful for her and her students. The opportunity to welcome a researcher to their classroom to teach methodologies on how to lead their own investigations and learn more about climate change and its local impacts could potentially enable access to their own emancipated research practice.

In thinking through a movement school and place-based learning centre, we imagine Casa dels Futurs as being a situated research centre wherein research skills, local and subject based knowledges and know-hows from peoples of all backgrounds are exchanged through a collective learning process. This process, and thus Casa dels Futurs as a project, then aims to support deeper explorations and understandings about the world around us as a part of collective struggles for more just and sustainable futures.

—

Reference:

Gruenewald, D. A. (2003) The best of both worlds: A critical pedagogy of place, Educational Researcher, 32 (4), pp. 3–12.

—

Dan Papillon is a member of the collective project Casa dels Futurs, biologist and sociologist in training.

Austin Matheney is a doctoral student at the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and the Barcelona Lab for Urban Environmental Justice and Sustainability (BCNUEJ) and member of the collective project Casa dels Futurs.

Nelly Alfandari is a member of the collective project Casa dels Futurs, and works with popular and critical, place-based pedagogies as educator, researcher, and activist in different contexts and settings.

Casa dels Futurs (“The House of the Futures”) is a Barcelona based project project to create long-term physical and educational infrastructure to better support social and ecological movements to build solidarity and cooperation in the time of climate crisis.

Drawings: Cristina Fraser