By Achim Klüppelberg

Reflections on powerlessness and empowerment for a just energy transition in the aftermath of the struggle against coal mining in the village of Lützerath in Germany.

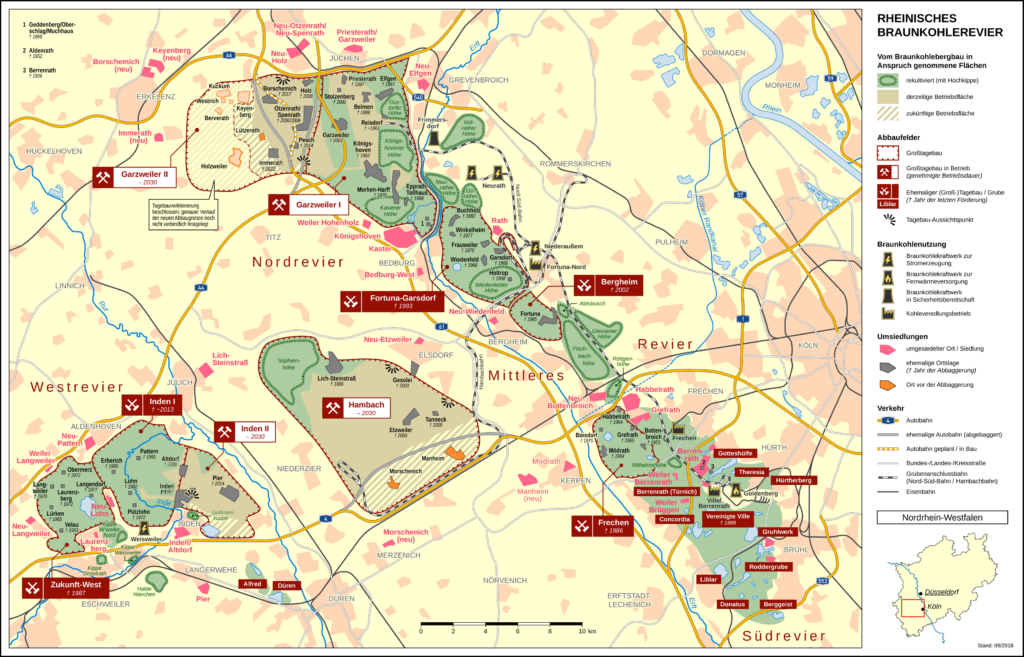

On 14 January 2023, the international climate movement met at the open pit lignite mine Garzweiler II in Western Germany to protest the continuous coal mining by the corporation Rheinisch-Westfälisches Elektrizitätswerk, better known as RWE. Within the context of the ongoing climate emergency, protests against the mine had been going on for years. But the recent expansion plans moved the focus of the climate movement from the Hambach Forest to Lützerath. Garzweiler is one of Europe’s largest coal mines, and thus one of the biggest sources of CO2-emissions in the energy sector.

The culmination point of years of protests became the little village of Lützerath, which was squatted for about two years to prevent RWE’s large digging machine to destroy its houses and to get the coal beneath it. On this day, approximately 35,000 people travelled to the pit colloquially known as “Mordor”, an huge desert-like moonscape with coal power plants blowing their climate-destroying fumes into the air, clearly visible at the horizon.

“Rheinisches Braunkohlerevier” made by Thomas Römer with Open Street Map data. CC BY-SA 2.0.

The protesters came as individuals or together with different organised political groups. Among those were official parties, such as the Green Party, large environmental non-governmental organisations, such as Greenpeace, BUND, NAJU, NABU, Fridays for Future, Students, Parents and Scientists for Future, civil society alliances such as Wald statt Asphalt [Forest instead of asphalt], Alle Dörfer bleiben! [All villages stay!], Klimaallianz Deutschland [Climate Alliance Germany] and ADAC, queer and LGBT groups, the Christian group Die Kirche(n) im Dorf lassen [Leave the church(es) in the village], hippies, as well as left-wing initiatives from anarchists to squatters. International guests came to the event, like Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg.

All of these groups came together around the goal of defending Lützerath against RWE to keep the coal in the ground, protect local villages, and to ensure that Germany would stay committed to its 1.5 °C-climate goal as agreed in the Paris Agreement. If all the coal beneath Lützerath would have been used in thermal power plants, Germany would have failed its climate commitments. Crucial in this regard were climate tipping points, which if overstepped would spiral the situation out of control. For activists, the village represented the physical 1.5°C-limit: if it were to fall, the climate goals would fall, too. Apart from this hands-on aim, left-wing groups also wanted to create an alternative society in Lützerath, as had been practiced in other squats such as those in the Hambach Forest, the Dannenröder Forest, and others.

If this effort to cancel coal mining at Garzweiler would have been successful, the locals could have kept their homes and their way-of-life. The region could have avoided significant impacts on groundwater levels, air/water/land pollution, biodiversity, and agriculture. Germany could have avoided compromising its so-called Energiewende (energy transition), and the European Union could have reduced overall greenhouse gas emissions.

Feeling the need to become active and protest the injustice of climate destruction, I travelled to Lützerath and participated in the protests on 14 January 2023. In the weeks after, I was able to get in contact with five other participants. We conducted interviews* during the spring of 2023. This text stems from both these interviews and my own experiences on-site, as well as literature on the events.

Squatted Backsteinhof in Lützerath 2021. “1,5°C means that Lützerath stays!”; “Excavator for sale for 1,5°C”. By © Superbass CC-BY-SA-4.0 (via Wikimedia Commons).

The strategy of the climate movement regarding Lützerath was plentiful. First, an enormous effort was made to inform people about what was going on. The aim was to mobilise as many as possible for both the actual squats in Lützerath but also for the large demonstration on 14 January 2023, which became known as Tag X (“Day X”), a synonym for the day before Lützerath was supposed to be dug away and evictions were about to start. This demonstration was a cornerstone of the strategy, but by far not the only one. Numerous rallies throughout Germany were conducted in solidarity, information events held, posters and stickers distributed, social media campaigning included, and left-wing activists tried to revive Lützerath. They started living there and to build and grow a space in which utopia could be realised, despite or maybe even because the lignite pit got larger and larger, encroaching upon the hamlet.

Squatting Lützerath to prevent RWE from digging out the coal beneath the village had the aim to postpone the day when the company could make profits from the resource by indefinitely dragging out the process and increasing costs. This tactic was successful in the struggle for the Hambach Forest since 2012. The successful struggle in Hambach motivated many to join the protests for the survival of Lützerath.

Furthermore, the official story justifying the usage of coal beneath Lützerath based this climate-harmful endeavour on the procurement of arguably essentially needed energy supply for the whole country, which allegedly could have overruled climate commitments. On the one hand this was a path-dependent continuation of German energy policy from the times of industrialisation in the 19th century until today. On the other, it was a stern 180° change of position for the new government around chancellor Olaf Scholz, who led a coalition between Social Democrats, the Green Party and the Liberals that presented itself as being committed to mitigating climate change during election campaigns in 2021.

Ostensibly, the coalition changed its announced policy back to conventional German energy strategies because of the war between Russia and Ukraine that dramatically escalated on 24 February 2022, the following deliberate and unilateral decision by the government to stop fossil fuel imports from the aggressor, the destruction of Nord Stream I and II, as well as the intentional inability to create a sustainable change in Germany’s energy mix based on renewables now and during the last decades. To add injury to insult, the German Green Party both ruled the federal energy ministry and the regional environmental ministry concerned with Lützerath: Instead of fighting RWE, their leading board embraced the company’s goals and sanctioned the destruction of the village.

Contradicting this change in policy, the highest court of the country had previously decided several lawsuits in a way that practically elevated climate change mitigation policies into constitutional law. The German government argued on the basis of limited scientific evidence heavily influenced by RWE and issued by the regional economy ministry that the coal beneath Lützerath would have been needed to avoid the breaking down of energy systems during the winter period of 2022-2023.

To formulate a compromise, the Green Party turned in favour of digging out the coal under Lützerath and forfeiting the 1,5°C-goal, but in exchange wanted to make RWE stop at the Garzweiler lignite pit after that, protecting the villages Kuckum, Berverath, Keyenberg, Oberwestrich and Unterwestrich that lay west of Lützerath and that the company wanted to destroy next. On 04 October 2022, RWE, regional economy minister Mona Neubaur and federal economy minister Robert Habeck (both from the Green Party) publicly proclaimed this deal at a press conference. Furthermore, the federal stop of generating electricity by burning lignite was to be antedated from 2038 to 2030, which the Green Party marketed as a success.

In opposition to that alternative scientific reports were made, questioning the soundness of this assessment and this deal. Several already existed before the decision was taken. Ignoring science, RWE wanted to be fast and to go ahead before a renewed discussion of the matter could possibly change the decision. The activists hoped that by dragging out the protests, the regional and the federal governments could have time and feel the urge to reassess, which could have given the Green Party some leverage to prevent the destruction of Lützerath.

“Let’s go to Lützerath! Stop eviction! For Climate Justice!” – Mobilising poster of the climate protests taking place at the Garzweiler lignite mine. Provided via Fridays for Future for distribution. Co-production of the different initiatives stated at the end of the poster.

According to RWE, Garzweiler produced up to 30 million tons of coal on an area of 35 km² by digging away 100-120 million m³ per year. During the last years, the mine was continuously expanding, eating away fertile agricultural land and rural communities on its way to Lützerath. With the climate crisis escalating dramatically during the last five years, the village became a focal point for the German and international climate movement.

Events flamed up on 11 January 2023, when the police started the forceful eviction of activists from Lützerath and the surrounding area. While preparing for day X, activists had erected barricades out of stones, logs, concrete, and steel. They also tried to block paths and roads with the basic tools they had available. Fences that were built by the police were torn down by activists.

Again and again, protestors tried to squat heavy eviction and RWE’s digging machinery. At the same time, many demonstrations popped up around the whole republic, including protests in front and inside of the Green Party’s regional headquarters in Düsseldorf. Activists both held out on the roofs of buildings and in tree houses, where it was very hard to evict them, and in a tunnel, two guys dug out beneath Lützerath.

At the same time, protests targeted the central business building of RWE, where people chained themselves to the plant’s gates. At the fellow lignite mine in Hambach, activists squatted one of RWE’s large excavators in solidarity. Besides the struggle to protect the climate, it was also important to show that the German state would dispossess some of its rural citizens for outdated resource extraction, even in 2023. People had to lose their homes to fuel RWE’s profit interests. Furthermore, in many of these small villages that already were or were to be destroyed, churches were being desecrated even though the local people wanted to continue their operation. In this regard parts of the struggle also had a religious component to it.

The large, rainy and muddy demonstration on 14 January 2023 was the culmination point of all those activities. It was a powerful protest, certainly one of the larger climate demonstrations in Germany. Nevertheless, the amount of people attending was a contested issue for the interviewees. In the immediate aftermath of the demonstration, it became apparent that there was a large discrepancy between the number reported by the police (15,000) and the one by activists (50,000). The actual number might have been between 30,000 and 39,000. This discrepancy was one of many contested issues in regard to media reporting on the demonstration that undermined enthusiasm in the political process and the independence of the media. For some, the amount of attendees was encouraging, and for others it was disappointing if compared to the turnout to a football game or to former Fridays-for-Future-demonstations.

Unfortunately, the demonstration and all the different creative actions in so many places aiming at preserving Lützerath and keeping the coal in the ground, were futile in the end. Lützerath was destroyed and the coal has been dug up, public climate commitments, the Paris Agreement, and continuing protests notwithstanding.

RWE’s large digging machine standing opposite of the town of Lützerath at the top-right corner, surrounded by police. The yellow-vested-people standing next to the excavator are private security guards defending the machine against squatting attempts by protesters. By the author, taken on 14 January 2023.

The village is gone, but Lützerath lives on

The protests that went on for years and culminated in the large demonstration on 14 January 2023 were unsuccessful in the sense that Lützerath did not survive. Protesters, activists, and climate enthusiasts had to realise that in this instance, the combined force of big capital in the form of RWE, a compromising regional and federal government, as well as a chancellor who took climate commitments by himself and by his own party not serious, the limits of their influence was reached. The village is gone. It will not have a future. The people who have left, who were evicted and the ones that took the deals offered will not return. To cover their tracks and hide the hideous landscape they have created, RWE and the province plan to fill the huge mining pits with billions of litres of water from the Rhine to create several huge lakes. The realisation of this idea is highly questionable. During the last summers, the region experienced droughts and the Rhine’s water levels had dropped. To continuously divert a significant part of this river will not be a sustainable solution, as everyone downstream will suffer. It will not work.

Nevertheless, Lützerath did a lot to many individual people in particular and the climate movement as well as the general discourse in general. For me, the urgency to act within the context of the ongoing climate crisis is apparent, the greediness of the coal company appalling, the complicity of large parts of the political establishment open for everyone to witness, disregarding previous announcements, climate agreements, and election programmes. People see this and the discrepancy cannot be hidden anymore. The German state does not take its own climate goals serious. Instead it promotes the usage of the dirtiest energy option there is: open-pit lignite mining.

One important question to ask in this regard is whether RWE will have to stop digging coal in the area, as this was the deal with the government, or whether the company will be allowed to continue. If they will be stopped, at least Lützerath’s neighbouring villages could be saved and the area preserved.

That being written, it is more probable for me that another village at the Garzweiler lignite mine will be threatened to be dug away. If that happens, people will go there again and take the spirit of Lützerath with them to continue the struggle. Then even more people will support it and the next village will be saved, as strategies evolve and divisions amongst the movement dissolved. We have one planet and only one joint future on it. Globally, Lützerath might only be one of many frontlines of the climate crisis. But the more we zoom in, the more important it becomes for the people closeby. Another world is possible, we just need to be brave enough to act outside established norms. Lützerath has shown that change will not come from above, but that it is already here in the present, created by average people who dared to act. This gives hope to continue, hope to accept this setback, and hope to work together for a better world, in which we do not jeopardise everything for the greed of a few but powerful people. Lützerath lives on.

* Interviews for this text: Kim (works with water protection and water dynamic in Germany). Interview on 25 April 2023 via Zoom in Stockholm. First name basis; Marlon (Climate activist, Gießen, Germany). Interview on 22 April 2023 via Zoom in Gießen and Stockholm. Pseudonym; Maxi (Climate activist, near Frankfurt, Germany). Interview on 24 April 2023 via Zoom in Stockholm. Pseudonym; Micah (Climate activist, Darmstadt, Germany). Interview on 05 April 2023 via Zoom in Darmstadt and Stockholm. Pseudonym; Pieper, Fabian (communal politician in Krefeld-Fischen, Green Party, Germany). Interview on 12 April 2023 via Zoom in Krefeld and Stockholm.

This text was written in the context of the Occupy Climate Change! online school taking place in spring 2023. Check out the Atlas of the other worlds, an online collection of environmental struggles across the globe. You will also find an entry about Lützerath, based on the work presented here. I am indebted to my wonderful interviewees and to the organisers of the online school, especially Anja Moum Rieser and Marco Armiero: Thank you!