By Claude Péloquin

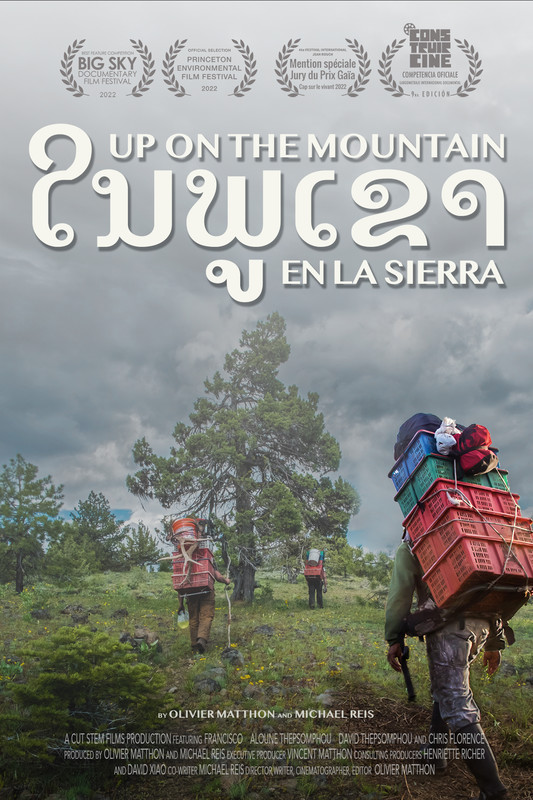

The documentary film Up on the Mountain is a social portrait of the commercial harvest of wild mushrooms in the forests of western North America.

A trade in symbiosis with the forest

The ecology of wild mushrooms is diverse and complex. Some kinds of mushrooms grow from the decomposition of plants and other organic matter in the forest. Others grow from the symbiotic exchange of nutrients with trees and other plants. Still others have a parasitic relationship with this same vegetation. The distribution and vagaries of wild mushrooms’ growth — of their emergence — varies enormously from one season and from one place to another. Mushroom pickers must know where and when to look in order to find them. This requires sophisticated knowledge of succession dynamics in these ecosystems: rain, temperature, forest fires. It also calls for patience; and efforts to find mushrooms do not always yield good results.

Professional mushroom pickers spend multiple weeks traveling the back-country of western North America, from California to Alaska. The film Up on the Mountain follows three groups of pickers in Oregon, Idaho and Montana.

From their semi-temporary camps set up for a few days or even a few months, near one promising area or another, mushroom pickers set off to hike in the forest, their harvesting knife in one hand, and — harnessed to their back — the harvesting basket they hope to fill with mushrooms.

Scene from the movie Up on the Mountain. Source: Olivier Matthon, used with permission.

Harvests will later be sold to buyers who have set tables, balances and bins at the back of their pick-up truck, parked in nearby parking lots. These buyers, whose work is almost as “artisanal” as that of mushroom pickers are the entry point to the mushroom trade networks that supply restaurants in North America, Europe and Asia.

A socially and politically ecological documentary

In the film, we learn that mushroom pickers are mostly, but not exclusively, immigrants from Southeast Asia and Latin America. While some harvesters may be attracted to the semi-nomadic lifestyle that characterizes this trade, many are undocumented migrants and racialized people who live in the US but have little to no English proficiency. For them, mushroom picking is a viable alternative to the exploitation they would face in the context of other work available to them – such as fruit and vegetable picking, or meatpacking. Mushroom picking is also an appealing alternative to those who do not have access to loans or property to get started in business. As some of them explain in the film, they engage in this business drawn to the possibility of being “their own boss”, enjoying a sense of freedom out in the forest.

As is the case with many artisanal practices, the commercial harvest of wild mushroom is a trade learned with experience. It does not require diplomas or certification; nor does it require significant capital investment. One must have the time, be in good physical health, and want to be outdoors for long hours, in any weather condition in the pursuit of these ephemeral organisms.

Scene from the movie Up on the Mountain. Source: Olivier Matthon, used with permission.

Scene from the movie Up on the Mountain. Source: Olivier Matthon, used with permission.

At the same time, working in nature brings its share of unpredictability, and even though mushroom picking can be somewhat lucrative under certain conditions, it is not a gold mine, or easy money.

The state does not know what to do with this practice

Up on the Mountain touches on several elements of the political geography and political economy of nature that mediates access to forests, which, in this case, translates into an incapacity of the state to enable this commercial harvest.

Scene from the movie Up on the Mountain. Source: Olivier Matthon, used with permission.

Scene from the movie Up on the Mountain. Source: Olivier Matthon, used with permission.

We see rangers of the United States Forest Service preventing mushroom pickers from accessing sites, threatening them with reprisals, seizing their crops, and denouncing them to immigration services. All of this happens even if mushroom picking seems entirely compatible with the mission of the public forests and the mandate of the Forest Service.

The United States Forest Service has the mission of creating and managing public forests to ensure a balance between the exploitation of resources, the conservation of ecosystems, and the recreational activities of the public. Mushroom picking is compatible with these three goals.

Unlike other commercial activities exploiting natural resources in highly unsustainable and destructive ways — such as logging operations, mining, or even livestock grazing —picking mushrooms does not, in itself, have negative impacts on ecosystems. The mushrooms harvested in the film — chanterelles, burn morels, and matsutake — are ephemeral: only their reproductive part is harvested while the main part of the organism remains underground. New mushrooms will surely grow the following years, regardless of whether they are picked.

The environmental impacts of mushroom picking, as minor as they may be, are most likely caused by walking in the forest and setting up camps. These impacts can easily be minimized, especially as mushroom pickers usually work in small groups spread across large forest areas.

Finally, the use of the forest by mushroom pickers is in some ways similar to that of recreational activities such as hiking and camping. Yet it attracts a “different clientele”, one whose temporal and spatial relationship with the forest differs from that of outdoor enthusiasts typically well received in parks and other large natural public spaces. For example, it is reasonable to suspect that, for some rangers, the mushroom-picking camps made up of makeshift shelters by semi-migrant workers clash with the forest landscape aesthetics sought by the Service. In fact, these camps may appear unkempt: they do not look like the organized workers camps set up by logging companies nor they look like the clean and contained short-term camps of typical outdoor enthusiasts set up at designated campgrounds.

Added to this is the dimension of race: it appears that there is a certain degree of racial discrimination perpetrated by the rangers of the Forest Service towards Asians and Latin Americans and their use of resources. Moreover, the Forest Service seems to suggest that the commercial collection of wild mushrooms does not fit well with the predefined categories derived from the utilitarian history of resource management. Yet it is not clear how they see it as incompatible with any of them and for this reason they do not really know how to behave with mushroom pickers. This makes it, in my opinion, an excellent case-study in the most classic tradition of political ecology in geography and anthropology.

The film does not get lost trying to explain everything and answer all these questions, but rather sticks mostly to the experience of the harvesters, which it does very well. On the other hand, the Forest Service turned down the majority of interview requests for the film.

Scene from the movie Up on the Mountain. Source: Olivier Matthon, used with permission.

Scene from the movie Up on the Mountain. Source: Olivier Matthon, used with permission.

Scene from the movie Up on the Mountain. Source: Olivier Matthon, used with permission.

For these reasons, I think that the film is ideal material for an advanced university course in geography, anthropology and other humanities dealing with nature-society relationships: perhaps precisely because it brings many questions to the attention of the listener without necessarily giving simple or prefabricated answers.

Where does the harvest of wild plants and fungi fit in the global economy of the 21st century? Are the obstacles to harvesting posed by the Forest Service the manifestation of something broader? What is the role of rangers and of the Forest Service in general? How are they perpetuating racial discrimination through their work in the forest? What kind of aesthetic considerations should be applied to forest management?

Is mushroom harvesting a source of unease among forest managers because it “overlaps” too much with the different categories of activities conceptualized by the utilitarian management framework of the modern forest? Is it one of those “impure” nature-society hybrids that Bruno Latour would say the moderns do not want to see? Is it possible that the Service does not know how to deal with mushroom picking because it is simultaneously too “wild”, too “commercial”, and too “recreational”? And if so, how could this incompatibility be solved?

The film also shows the value of rigorous, patient, and honest ethnographic work. The director, Olivier Matthon, has himself been a professional picker for more than ten years, and is also a resident of one of these small rural localities on the edge of a public forest in the state of Washington.

Watch the trailer of Up on the Mountain here: https://vimeo.com/259953659

Up on the Mountain, Olivier Matthon and Michael Reis, documentary film, 84 minutes, USA, 2021, English, Spanish and Lao, with English subtitles. https://uponthemountainfilm.com/

——–

Claude Péloquin is a geographer living in Québec. He writes and teaches on the historical and political geography of environmental management expertise in rural North America and West Africa.

This review was originally published in French on cpeloquingeo.com.