By José Ramón Bertomeu Sánchez.

Massive pesticide usage was created through the disciplining of farmers in the use of new chemical technologies during Franco’s dictatorship, contributing to concealing the slow and invisible poisoning of agricultural workers and consumers, leaving a toxic legacy in Spanish agriculture up to today.

Disciplining farmers in the use of new chemical technologies was part of the patriotic fight against insects aimed at protecting the food supply and encouraging the development of national industry on the road to self-sufficiency prompted by the new authoritarian state. The co-production of Franco’s regime and the new forms of chemical pest control created long-standing social and discursive practices, which contributed to concealing the slow and invisible poisoning of agricultural workers and consumers. These architectures of ignorance endured years beyond the Francoist regime and encouraged the massive usage of pesticides in Spanish agriculture which remains nowadays as a toxic legacy.

Today, at the beginning of the 21st century, Spanish agriculture is one of the main consumers of pesticides in the European Union. This is different than the first half of the 20th century, when agronomists lamented the low use of fertilizers and pesticides as one of the causes of the “backwardness” of Spanish agriculture. To understand the dramatic change in pesticide use during the last century, I suggest paying more attention to the early years of the Francoist dictatorship in the 1940s, when arsenic pesticides were massively introduced in Spain.

This group of dangerous pesticides had been globally introduced at the end of the 19th century by adapting previous arsenical compounds, such as the so-called “Paris green”, or new ones such as lead arsenate. They became the most popular pesticides before the advent of DDT and other synthetic ones after the Second World War. Then, large amounts of arsenic compounds became available at low prices as by-products of the emerging heavy chemical industry (Romero, 2021). Chemists, engineers and businessmen were pleased to see this highly toxic waste of their industries being transformed into a marketable product which could be sold to farmers for pest control. This broad availability of toxic products (such as arsenates) contributed to the marginalization of other technologies for pest control in the 20th century (e.g. mechanical methods).

Fig 1. Several leaflets published by Spanish agricultural engineers on the Colorado beetles during the 1940s. Source: Vicent Peset Llorca Library, Institut López Piñero, Universitat de València. Pictures by the author.

In Spain, which was lacking by then a chemical industry producing large quantities of toxic waste, the arrival of arsenic pesticides took place thanks to a number of ecological, political and economic factors converging around the early 1940s. Most importantly, a new pest affecting potato production, the Colorado beetle, moved eastward from the center of the USA to the Atlantic coast and reaching Europe at the first decades of the 20th century.

In Spain, as elsewhere, several regulations were implemented to avoid the circulation of infected potatoes, such as burning fields, using high quantities of toxic pesticides, controlling imports, and establishing quarantine zones. Agricultural engineers organized international conferences to discuss other measures to be adopted for the control of the pest, but were all in vain.

At the Iberian Peninsula, the Colorado beetle was firstly detected in northern Catalonia, near the Pyrenees, during the summer of 1935. Drastic steps were taken: the area was isolated, the potato harvest was destroyed, and all the surrounding fields (more than forty kilometers around) were treated with arsenic pesticides. This first episode was successfully contained, but the frustrated military coup against the democratic government in July 1936, which unleashed the Spanish Civil War, dramatically reduced the resources for controlling the pest. The situation was alarming as potatoes were one of most important crops in Spanish agriculture and these post-war years were marked by famine, state violence and political terror.

This challenging situation (a political and agronomic crisis) encouraged the intensive use of pesticides which so unsuccessfully had been prompted by Spanish agricultural engineers during the first decades of the 20th century. Just at the end of the Civil War, at the beginning of the Francoist dictatorship, new services for pest control were created, including a special office for dealing with the Colorado beetle. Agricultural engineers coordinated an extended network of provincial agriculture offices and experimental stations, which had been set up during previous decades.

In each Spanish province, at the top of the agriculture office, an agricultural engineer oversaw the campaigns against the Colorado beetle, which included a broad range of multimedia activities addressed to the farmers: talks, practical courses, leaflets, articles in newspapers, radio broadcasting, and even documentary films. Agricultural engineers also handled the acquisition of arsenic pesticides and spraying equipment, which were distributed for free (or at low price) to the farmers to encourage further investment in these products.

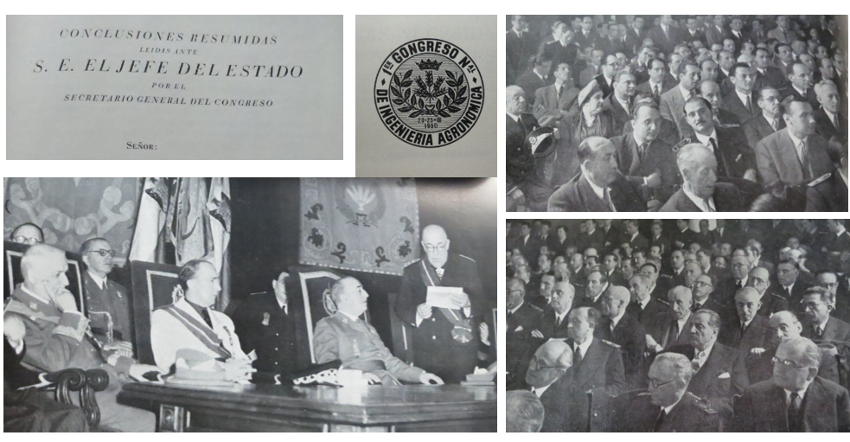

Fig 2. Several images of agricultural engineers at the National Meeting organized in Madrid in 1950 under the presidency of General Franco (left below). Pictures from the book: Congreso Nacional de Ingeniería Agronómica. Madrid: Asociación Nacional de Ingenieros Agronómos, 1950. Personal collection.

Apart from the new pest, the arrival of arsenic insecticides was favored by the autarkic policies of the early Franco governments, which sought to promote industrialization by mobilizing natural resources – in this case, the arsenic mines located in the northwest of Spain. Moreover, in order to protect the national industry, new regulations concerning the trade of pesticides were introduced during the early 1940s. A “National Register for Phytosanitary Products” (“Registro Nacional de Productos Fitosanitarios”) was created, almost at the same time as a similar register was implemented in Vichy’s France.

A special procedure was created for the registration of imported pesticides to be sold in Spain. The restrictions to foreign companies favored the emergence of local pharmaceutical and agrochemical companies with a reduced number of employees, including some chemists, agricultural engineers or entomologists. Some of these companies grew during the following decades and turned into important pesticide industries during the 1960s. They co-existed with many small producers and retailers whose activity was however less persistent.

Apart from promoting national industry, the register was intended to guarantee the quality of pesticides, that is, to confirm their deleterious virtues on bugs and their harmless effects for plants. As many engineers recognized, fraud and lack of efficacy undermined the credibility of the chemical methods for pest control, making even more difficult to convince farmers to follow the official guidelines against the Colorado beetles. Following the new regulations, samples of the new pesticides were sent to the provincial agriculture offices, whose directors wrote a preliminary report focusing on the producers and their capacity for making large amounts of pesticides, using if possible national natural resources. The reports usually also included information regarding political views and connections to the Francoist regime. In fact, many small producers, whose pesticides were officially registered, were political figures in their local contexts. Around a thousand of different products were analyzed between 1943 and 1950 and the number of the rejected proposals was around a quarter of those submitted.

With the help of chemists, agricultural engineers developed new tests adapted to the new synthetic products which replaced the arsenic pesticides during the 1950s. However, no information was required for the register of new pesticides regarding risks for cattle, farmers or food consumers. In other words, workers’ safety, public health, and environmental issues were absent from the National Register of Pesticides.

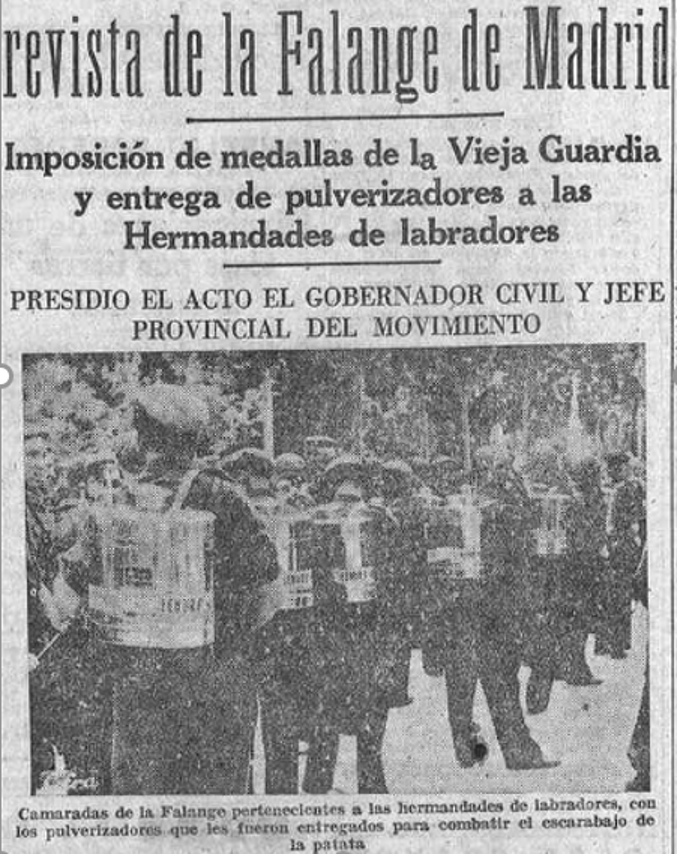

Fig 3. A group of young members of the Spanish fascist-like party (Falange), marching on and singing Fascist anthems, in front of the main political Francoist authorities in Madrid, with pesticide sprayers in their backs, intended to be employed in the campaigns against the potato beetle. Front page of the journal Hoja Oficial del Lunes, Madrid, 18 June 1945. Source https://prensahistorica.mcu.es/.

Summing up, arsenic pesticides should be considered socio-technological products that inform many features of the early years of the Francoist dictatorship. These products contributed to the consolidation of Francoism, while at the same time serving to introduce Spanish agriculture into the “vicious circle” of pesticides, through regulations which largely neglected the toxic risks. Thanks to these regulations, agronomic practices, and autarkic policies, the slow violence caused by arsenates was largely silenced, despite their very well-known risks to workers, consumers, and the environment.

This hints at several forms of production of ignorance concerning toxic risks. The Francoist regulations disregarded the available information concerning the toxic effects of pesticides, while promoting the introduction of new products, such as organochlorides as DDT, whose effects were unknown or had been scarcely studied, particularly when low doses and long expositions were at work. Neither human nor material resources were mobilized to deal with this massive poisoning, which explains the scarce data available for epidemiological studies or experimental research.

This lack of interest to pesticides impacts on health contrasts with the numerous studies conducted on the effects of arsenic pesticides on crops and insects which was supported by the new authoritarian regime to introduce, quickly and widely, arsenic pesticides in Spanish agriculture. While enjoying advantages for chemical pest control programs, agronomists helped consolidate the new Franco regime by providing technological solutions to the food crisis and connecting agriculture and industry through national raw materials in times of autarkic policies.

With the help of the new arsenic pesticides, both agricultural engineers and the new political authorities were able to present themselves as the main fighters against the invasion of the Colorado beetles, often using terms similar to those used against the antifascists groups or the previous democratic governments: Like the Civil War, the war against insects was presented as “a campaign of survival for the Spanish nation”, where the only possible option was “the extermination of the enemy” through extreme violence. Pest control activities were described using military terms such as invasions, contention, troops, weapons, annihilation, and so on.

Disciplining farmers in the use of new chemical technologies was part of the patriotic fight against insects aimed at protecting the food supply and encouraging the development of national industry on the road to self-sufficiency prompted by the new authoritarian state. The co-production of Franco’s regime and the new forms of chemical pest control created long-standing social and discursive practices, which contributed to concealing the slow and invisible poisoning of agricultural workers and consumers. These architectures of ignorance endured years beyond the Francoist regime and encouraged the massive usage of pesticides in Spanish agriculture which remains nowadays as a toxic legacy.

—

José Ramón Bertomeu Sánchez is professor of history of science at the University of Valencia. His current work is on the pesticide industry and the making of ignorance on toxic risks in 20th-century Spain. His last book is “Tóxicos: Pasado y Presente” (Barcelona, Icaria, 2021). More details in https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2040-4507.

Bertomeu Sánchez, José Ramón. «Arsenical Pesticides in Early Francoist Spain: Fascism, Autarky, Agricultural Engineers and the Invisibility of Toxic Risks». HoST – Journal of History of Science and Technology 13, n.o 1 (2019): 53-82. https://doi.org/10.2478/host-2019-0005.

Romero, Adam M. Economic Poisoning: Industrial Waste and the Chemicalization of American Agriculture. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2021.